On Jan. 22, 1973, the U.S. Supreme Court handed down its decision in Roe v. Wade, declaring that the U.S. Constitution contained a fundamental right to abortion. In one move, seven Supreme Court justices reinterpreted our nation’s founding document to invent a supposed right to kill unborn children. The decision affirmatively prevented the American people from protecting unborn human beings under the law, as many state governments had chosen to do in the years leading up to Roe.

Though nothing in the Constitution had ever said or suggested that women had the right to kill their unborn children, the court used it to sanction abortion, essentially on demand. Roe, along with its companion case, Doe v. Bolton, decided the same day, allowed virtually all abortions, at any stage in pregnancy, for any reason, across the entire country.

It was one of the most flawed decisions in the history of the court. In the ensuing decades, scholars on both sides of the issue agreed that the legal reasoning in Roe was highly political and radically divorced from any serious notion of what the Constitution required. Details that have since emerged about the machinations behind the scenes at the court leading up to the decision reveal that it was ideologically motivated and not judicially serious, crafted by so-called living constitutionalist justices who had little regard for the actual text or history of the Constitution. The seven justices who joined the majority opinion in Roe believed that, regardless of what was in the Constitution, they could — and perhaps even should — use the power of the court to short-circuit the abortion debate in the U.S. and put an end to the controversial issue.

Instead, quite the opposite happened. Roe easily could have been the end of the story, the final word in a brewing national debate that had yet to get fully off the ground. Yet almost 50 years later, on June 24, 2022, the Supreme Court revisited Roe and overturned it, declaring it a grievous misinterpretation and misapplication of the Constitution. In Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization, the court finally admitted its error and returned the question of abortion policy to the people and their elected representatives.

The story of how this dramatic change came about is a long and complicated one. There are the major players we all know and the major historical moments many of us remember, as well as countless forgotten heroes who fueled the pro-life movement at the grassroots level. But no understanding of those five intervening decades would be complete without a close look at the March for Life, which has convened in Washington, D.C., every January since Roe to rally the pro-life movement. The march has been perhaps the single most important vehicle, apart from voting, through which Americans over several generations told their lawmakers: Reverse this injustice and protect the unborn.

The origins of the march

As Ryan Anderson and I chronicle at length in our recent book, “Tearing Us Apart: How Abortion Harms Everything and Solves Nothing” (Regnery, $29.99), at the time Roe was decided, abortion was a live political debate. Americans had yet to reach a national consensus on how to handle the issue legally, but most states had laws in place protecting unborn children from the violence of abortion. With Roe, the justices attempted to put an immediate end to these debates over the legal, political and moral status of abortion by nullifying nearly every state law that prohibited or regulated abortion. Rulings in subsequent cases aiming to find the limits of Roe‘s logic showed that the justices didn’t intend to permit many protections at all for the unborn, even though the language of the ruling had appeared to leave room for states to act on behalf of the child in the womb.

It would have been far easier in the wake of the decision for opponents of abortion simply to give up on the issue entirely, or at least to develop a hyper-localized strategy rather than attempt to demand change at the federal level. Instances in which the Supreme Court had opted to overturn its previous flawed rulings are few and far between. There was little reason to imagine that it would be different in this case.

But thanks to the courage of pioneering pro-life leaders, the March for Life began to draw on the energy of pro-lifers across the country to make abortion a national issue, and one that remained relevant for decades. Shortly after Roe was decided, in the fall of 1973, leaders of the fledgling national pro-life movement met to discuss how they might commemorate the first anniversary of the ruling. They convened at the home of Nellie Gray, who was to become the founder of the March for Life, which she went on to lead for nearly 40 years.

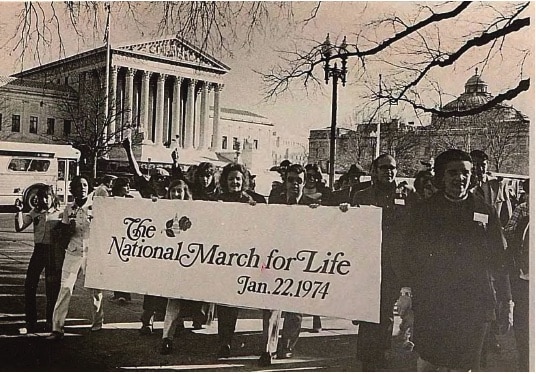

On Jan. 22, 1974, one year to the day after the fateful ruling in Roe, about 20,000 pro-life Americans marched through the streets of D.C. to lobby Congress, asking for a legislative response to what the court had done. At the time, these leaders planned a march on Washington and intended for it to be a one-time event. In those early days, pro-lifers were hopeful that Roe would swiftly be undone once federal lawmakers and the court realized how grievously wrong it had been.

But soon it became clear that the path to change wouldn’t be quite so immediate. Gray ended up leaving her career as an attorney to become the volunteer president of March for Life, and she went on to organize the event every year until her death in 2012, with fortitude that earned her the moniker “the Joan of Arc of the pro-life movement.”

Roe easily could have been the end of the story, the final word in a brewing national debate that had yet to get fully off the ground.

The march created momentum around the pro-life cause that prevented a preemptive surrender on the part of discouraged pro-life Americans. It quickly became one of the foremost reasons why they refused to give up on the issue after Roe and accept the court’s ruling. Ever since, the annual event has remained and one of the foremost means by which Americans have continued to express their outrage over what the court had done.

Under Gray’s leadership, the March for Life not only planned annual marches in Washington but also began lobbying on Capitol Hill for a “human life” amendment to the Constitution, one of the foremost policy efforts pro-lifers led in the years immediately following Roe. In addition to convening the march, the organization has continually played an important role in policy advocacy at both the federal and state levels.

The march and the GOP

It might be hard to imagine today, when the Republican Party platform aligns closely with the views of the most pro-life Americans, but in the wake of Roe, there was a significant divide within the GOP on the ruling and on the broader question of abortion policy. Prominent and influential Republicans such as Nelson Rockefeller favored legal abortion. First Lady Betty Ford praised Roe, calling it a “great, great decision.”

The March for Life was an essential player in challenging this divide and pushing for leaders across the political spectrum to reject Roe and legal abortion. While this effort failed when it came to the Democratic Party platform, which became steadily more and more in favor of legal abortion, the march and other pro-life activist groups succeeded in rallying Republican politicians and the GOP more broadly around a strong pro-life position.

In his 2016 book “Defenders of the Unborn” (Oxford University Press, $31.95), historian Daniel K. Williams writes of Nellie Gray’s response to Betty Ford shortly after Roe: “[She] announced in November 1975 that pro-lifers would hold monthly pickets outside the White House for an entire year, right up until election day, to protest the first lady’s comments and the administration’s support for legal abortion. ‘Betty, we don’t want the right to kill,’ one of their signs proclaimed.”

Just a few years later, the march found an important ally in Ronald Reagan, who had come to regret the fact that he had supported legal abortion during his time as California governor. During his 1976 bid for the GOP nomination, Reagan spoke in favor of the pro-life cause. Shortly before his 1980 campaign for president, Reagan wrote to pro-life congressman Henry Hyde, condemning Roe and voicing his support for a human life amendment to the Constitution. The letter prompted an outpouring of support from pro-lifers; Reagan was the first presidential candidate on either side of the aisle to endorse the Human Life amendment, which was the primary policy goal of pro-lifers at the time.

“The Reagan campaign team also capitalized on the annual March for Life in Washington by dispatching Senator Richard Schweiker to read a message of support for Reagan,” Williams writes. “Shortly after the march, Reagan sent March for Life Director Nellie Gray a letter of support and, at her request, a promise in writing that he would support the Helms-Dornan Human Life Amendment, the specific version of the HLA Gray favored. The next day, Gray sent her pro-life mailing list a letter endorsing Reagan for president.”

Thanks in large part to that alliance with Reagan and some policy successes during his presidency, the pro-life movement began to find its foothold as an essential coalition within the GOP, even as Democratic politicians who had once been pro-life declared themselves supporters of Roe and legal abortion.

A uniting force

The March for Life has played an essential role in national policy debates since its founding. But in the context of the broader pro-life movement, the march has always been known first and foremost as just that: a march. From Roe to Dobbs, it has served as an indispensable vehicle for millions Americans over the years to express their pro-life beliefs.

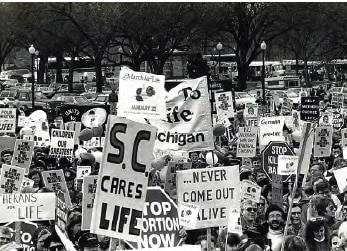

Perhaps more than that, it became the primary way for Americans to demonstrate that the right to life of the unborn child remained a matter of serious political and cultural salience, in spite of the court’s attempt at a final word and in spite of continued setbacks in the legal and political arenas. From its launch that very first year after Roe, the march has been the most centralized and galvanizing force to unite the pro-life movement. In a sea of strong voices and clashing opinions on the best way forward, pro-lifers have always agreed about the march — it’s where we all go in January, setting aside our differences to stand together and say, enough.

Perhaps one of the biggest signs of the event’s growing success and influence has been the rally hosted on the national mall right before the group marches through the streets of Washington, past the Capitol and to the Supreme Court. At the march that marked the 25th anniversary of Roe, the rally featured remarks from three former pro-abortion activists — Dr. Bernard Nathanson, founder of pro-abortion group NARAL; Norma McCorvey, the Jane Roe of Roe v. Wade; and Sandra Cano, the Mary Doe of Doe v. Bolton.

Nathanson, who had performed or overseen more than 60,000 abortions, had come to realize the humanity of the child in the womb, abandoned his practice of abortion, and become a formidable pro-life leader. Nathanson closed his brief remarks at the march with lines from Churchill, as applicable today as they were then: “If we adhere faithfully to [our promise] and walk forward with sober strength seeking no one’s land or treasure, seeking to lay no arbitrary control upon the thoughts of men; if all [American] moral and material forces and convictions are joined with your own in fraternal association, the high roads of the future will be clear, not only for us but for all, not only for our time, but for a century to come.”

As the march increased in importance, particularly as a rallying point for pro-lifers who wanted more action from federal officials, prominent Republicans began to appear to address the crowd. George W. Bush spoke to the rally remotely several times during his presidency. In 2017, Mike Pence became the first vice president to deliver remarks to the rally in person, and in 2020, Donald Trump became the first president to do so.

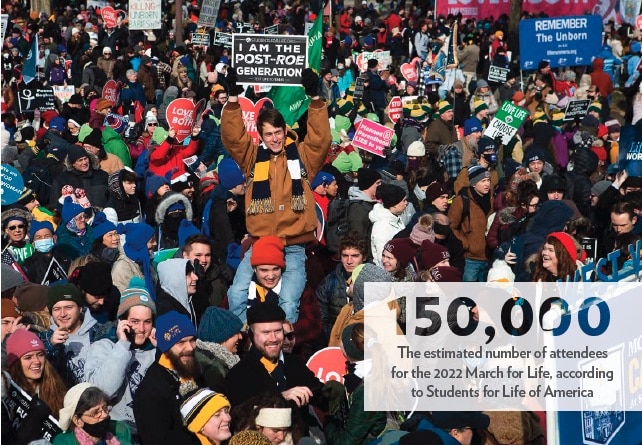

Abortion advocates often depict the pro-life movement as a monolith, made up of men who are older, white, often Christian and usually Republican. In reality, the coalition of Americans who believe in the dignity of life in the womb is quite diverse, and quite young. One report from 2010 estimated that as many as half of the attendees at the march were under 30 years old.

The anti-abortion movement is one of the most diverse political coalitions in the country, united not by creed or identity but by belief in the sanctity of human life. This is never on more prominent display than at the march, where Americans from markedly different cultural backgrounds, religious views, and political orientations gather and set aside their disagreements to campaign against abortion.

In more recent years, led by its new president, Jeanne Mancini, the march has begun to do more to communicate that diversity of perspectives, particularly through its annual themes such as “Equality Begins in the Womb,” “Unique from Day One: Pro-Life is Pro-Science,” and “Life Empowers: Pro-Life is Pro-Woman.” For the 2023 March for Life, the first since Dobbs, the theme will be “Next Steps: Marching in a Post-Roe America.”

“Even with the wonderful blessing of Roe v. Wade being overturned, which allows more freedom at the state level to enact pro-life laws, the necessary work to build a culture of life in the United States of America is not finished,” the March for Life website states. “Rather, it is focused differently.”

Forward in a post-‘Roe’ world

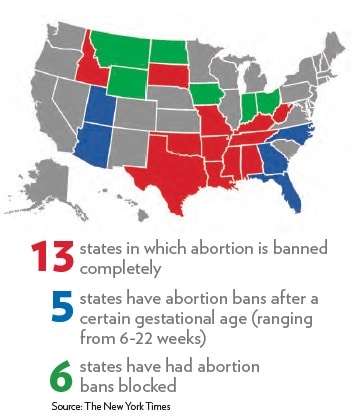

The organization’s leadership is right to recognize that the fight over abortion in the U.S. is far from over. Dobbs was a major victory and an essential first step toward building a pro-life country. But the end of Roe didn’t put an end to the fight over abortion. Instead, it triggered a new debate, which is now unfolding in every state, as Americans once more face the task of determining what they believe about abortion and what our laws should do. Much of that battle will take place politically, legally and legislatively as we have already witnessed in the wake of Dobbs. But there is also a major cultural battle to wage, and the March for Life has always been an essential part of that fight.

Here’s how the organization has explained why the annual march on Washington will continue in a post-Roe country: “Our most important work is changing hearts and minds. The goal of the national March for Life is to not only change laws at the state and federal level, but to change the culture to ultimately make abortion unthinkable.”

The group has also said it plans to expand its focus and organize more marches at the state level, which it had done occasionally in the few years before Dobbs. Already, there are 2023 marches planned in Arizona, California, Connecticut, Ohio and Virginia. In addition to this new initiative, the march promises that it “will continue to march every January at the national level until a culture of life is restored in the United States of America.”

This promise echoes a remark attributed to Nellie Gray in the early days of the March for Life: “We will be here until we overturn Roe v. Wade, and believe me, we are going to overturn Roe v. Wade.” Though she didn’t live to see Roe‘s downfall, Gray and her March for Life were a significant part of bringing about this new dawn for the pro-life movement.

The anti-abortion movement is one of the most diverse political coalitions in the country, united not by creed or identity but by belief in the sanctity of human life.

“The thousands of young demonstrators waving signs at the March for Life that said ‘I am the Pro-Life Generation’ were probably not sufficient to reverse the larger cultural shifts that led to abortion legalization,” Williams writes in the conclusion to Defenders of the Unborn. “But they were a sign that the movement was not going to lose its fervor anytime soon. They were a sign that the future political prospects for the movement might be better than some had once expected. They might have even been an indication that Roe v. Wade would not last forever.”

As it turns out, they were. The March for Life was then and is now a sign that the pro-life movement refuses to give up on the dream of a country in which every human being, born and unborn, is welcomed, valued and cherished. In the wreckage left behind by Roe, a new generation of pro-life Americans is ready to keep marching.

Alexandra DeSanctis is a fellow at the Ethics and Public Policy Center and a columnist for National Review. She is co-author, with Ryan T. Anderson, of “Tearing Us Apart: How Abortion Harms Everything and Solves Nothing.”