WASHINGTON (OSV News) — Are you looking to make an easy $1 million?

All you have to do is recreate a photographic negative image of an apparently crucified man on a 14-foot-by-3-foot piece of linen. And it has to have holographic features, so that when it is rendered as a three-dimensional profile based on the intensity of the shading, it should produce an accurately contoured 3-D image of a human form.

Oh, and — other than the linen, which will be provided — it all has to be done using only materials and methods that would have been available in medieval times, specifically between A.D. 1260 and 1390.

Maybe it’s not an easy million bucks after all.

That’s the challenge from David Rolfe, a British documentary film producer and researcher on the Shroud of Turin. He first announced the challenge to the British Museum in his 2022 documentary, “Who Can He Be?”

Dating the shroud

The British Museum supervised a carbon-14 dating of the Shroud of Turin in 1988, with a few labs from around the world. That testing pronounced that the shroud was not the genuine burial cloth of Christ, as many believe, because the testing showed it to be produced in the 13th or 14th century.

However, since then, many researchers have noted that the testing was flawed. Rolfe notes that carbon dating was new at the time, with only seven labs in the world capable of the work.

Any lab that got approval to work on the shroud would benefit from the publicity.

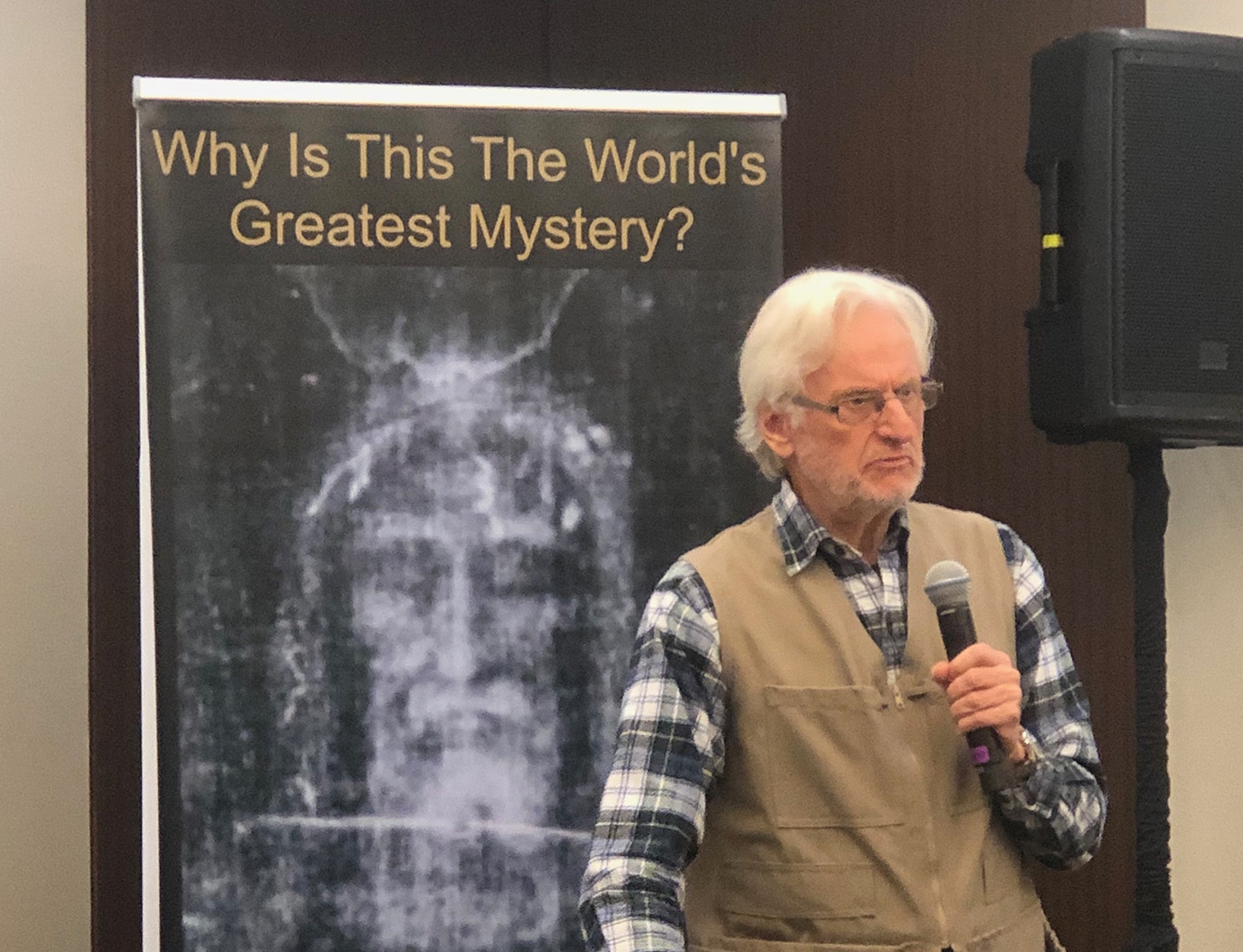

In Washington at a presentation after the National Catholic Prayer Breakfast Feb. 8, Rolfe said that the labs agreed on a protocol that would include taking samples from several different parts of the cloth for scientific accuracy. However, when it came time to take the samples, the custodian of the shroud, not wanting to harm its integrity, said a single sample should be taken from a corner of the cloth that showed signs of wear. One small sample from that area was divided into three samples for the labs to use.

The determination that the shroud had been created by a forger in medieval times, meant that “the shroud went from hero to zero,” Rolfe said.

But Rolfe added that the sampling created several problems. Engravings from centuries past show people holding the shroud for display, clutching the corners. People want a closeness to holy relics, he said, and “the tighter you grip it, the more benefit you get.” This introduced medieval pollutants to the cloth. He said restorers were very good at fixing important cloths and tapestries, to the point of repairs being nearly invisible.

If, as museum officials said in 1988, some resourceful artist in the 1200s “faked it and flogged it off,” then Rolfe and other shroud enthusiasts claim it should be reproducible, including the unique characteristics that show the image of a man on the cloth does not contain any paint, ink, dye, stain or pigments, and that there is no image underneath the blood stains.

Accepting the challenge

After almost two years of no response from the British Museum, the challenge is being extended to the United States by the National Shroud of Turin Exhibit, a group hoping to create a permanent museum space “in a city of museums” for a shroud replica and education, according to Myra Adams, executive director. The group currently has a mini-exhibit featuring an actual-size photographic replica of the shroud on display at the Catholic Information Center in Washington through the end of February.

The group announced the expanded challenge Feb. 8. Any person, organization or institution in the U.S. can apply to undertake the $1 Million Challenge to create the image of a crucified man that appears on the linen shroud. Up to three applicants will be accepted, each of which will receive three pieces of linen the same size as the shroud as the base for the recreation.

Rolfe said that many media outlets, especially in Britain, ran stories about the initial challenge to the British Museum, but none have followed up to find out if the museum has taken up the task, and if not, “Why is it leaving a million dollars on the table?”

A donor who helped Rolfe finance his 2022 documentary also agreed to put up the money for the prize. The same donor agreed to cover the U.S. prize, if anyone succeeds. “He thinks his money is safe,” Rolfe said.

Rolfe and other shroud experts say the unique characteristics of the shroud are more clearly revealed through modern science.

In May 1898, Italian photographer Secondo Pia, took the first photograph of the shroud. When he looked at the negative, he saw an appearance suggesting a positive image.

In more recent decades, other methods, including 3-D scanning for relative density have been used to study the shroud. “It keeps on revealing,” Rolfe said.

He added that the image is encoded with three-dimensional information. The blood stains on the cloth came first, the image at a separate time after that.

While the blood came from contact with a body, the image shows that the areas closer to the cloth are denser than others that are farther away, which is seen especially around the nose and eyes.

The prevailing theory is that an instantaneous burst of energy — possibly radiation — at the instant of the Resurrection, created the image on the shroud.

Analysis has shown that the image does not include any paints or other traditional media.

“The medium is energy. The image is not an additive process; it’s scorched,” Rolfe said.

But, it is scorched to the depth of only two microns — which corresponds to the thickness of the primary cell wall of the linen fiber, according to the challenge criteria — on the surface of cloth that is 200 micrometers thick.

A miracle for our age

“I think the shroud was created for the age we are in. Only our age has the tools to decipher the shroud,” Rolfe said.

He said that when the British Museum announced the carbon-14 results in 1988 and declared it to be a forgery, its scientists gave no indication that it was complex.

However, Rolfe and others such as Russ Breault, president of the Shroud of Turin Education Project, have looked at potential artists from the 14th century. They have found no art or artists from that time who worked with the kind of tools and techniques that could have created the shroud. And none of the extant artworks from that time period are done in the same style as that seen on the shroud, Breault said.

He added that forensic pathology shows wounds consistent with crucifixion, a practice the Romans ended in the 400s. And a recent archaeological find in Rome of a body that was crucified also shows similar wounds, including placement of the nails in the feet.

Rolfe said the judging process will be overseen by Paolo Di Lazzaro, a physicist who has studied the shroud.

But he said, in some ways, “We don’t need a judge. The essential characteristics of the shroud,” including the depth of penetration of the image and other criteria “are either right or wrong. It can’t be just something that looks like the shroud.”

The challenge website sets out seven criteria for a successful bid. “Contestants must be able to replicate the above seven features simultaneously in a single full-size front/back image, that is, with the same size and shape as the front/back figures of the Shroud of Turin using only materials and methods available to an alleged medieval forger.”

Rolfe said each applicant will receive three pieces of linen for the final project, to allow for some trial and error. He added that if applicants want to work on a 1-foot square, for example, “they ought to be able to get proof of concept.”

Christopher Gunty is associate publisher and editor of Catholic Review Media, the publishing arm of the Archdiocese of Baltimore.