“Our hearts are restless until they rest in you.” St. Augustine’s famous words addressed to God introduce his account of how a headstrong, self-indulgent young man became one of the most important Christian thinkers of all time and a saint. What follows — the story of Augustine’s conversion, as he tells it in his “Confessions” — is itself a landmark in Western spiritual and literary history.

Don’t look here for a flattering self-portrait, though. As one of this book’s many translators explains, the “Confessions” was written largely “to persuade Augustine’s admirers that any good qualities he had were his by the grace of God, who had saved him so often from himself.” In this, clearly, the volume succeeds beyond even the author’s hopes.

St. Augustine’s early life

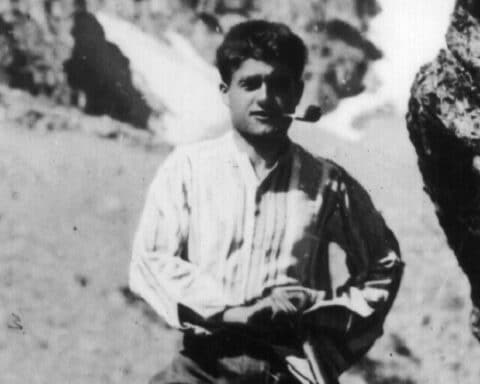

He was born in 354 in Thagaste (also spelled Tagaste), a Roman town in what is now Algeria. His pagan father, Patricius, was a landowner and minor official; his mother, Monica, was a devout Christian woman who eventually won her husband over to Christianity. Recognizing their son’s intellectual giftedness, his parents sent him, as a teenager, to study in Carthage — described by Augustine as “a hissing cauldron of lust,” where he indulged his own evil passions, took a mistress and fathered a son whom he called Adeodatus, which means “given by God.”

Read more from our Turning Points series here.

Amid all this, he nevertheless was at top of his class in rhetoric — an important discipline in those days, when the ability to speak well was an essential tool in practicing law, holding public office and many other pursuits. When he was 19, however, he read a book by the Roman statesman and philosopher Cicero that moved him to take up the pursuit of truth. Now began a tug and pull that would plague him for years. “Give me chastity and continence, but not yet,” he prayed.

Monica, his mother

Monica had seen to it that he became a catechumen as a child, but — not uncommon at that time — his baptism was put off till later. Now, reading the Bible and finding that it did not measure up to his sophisticated literary tastes, Augustine turned instead to the Manichees, a popular sect notable for its “dazzling fantasies” about the origins of evil. Horrified, his mother begged a Christian bishop to tell the young man to break off this attachment.

“Leave him alone,” he advised her. “He will see their errors for himself.”

The bishop was right. When a Manichean leader named Faustus with a reputation for wisdom visited Carthage, Augustine questioned him at length and found him intellectually shallow. Still, thinking he had nothing better to turn to, Augustine remained loosely associated with the Manichees.

Having taught rhetoric in Thagaste and Carthage and grown disgusted there at the rowdy behavior of the students, the young man moved to Rome to teach in 383. The following year, offered an attractive teaching position in Milan, at that time the seat of the imperial government, he moved there. He also made the acquaintance of the local bishop, Ambrose, and began attending church to hear him preach — not for the message of the homilies but for their literary style. After a while, though, the message of this future saint also started sinking in. So much, in fact, that now Augustine made a final break with the Manichees. But despite feeling increasingly drawn to Christian faith, he hesitated for fear of being wrong again. And besides — there were certain other ties he didn’t care to break.

Give me chastity, but not yet!

“Why do I delay?” he asked himself on turning 30. “Why do I not abandon my worldly hopes and give myself up entirely to the search for God and the life of true happiness?” But he already knew the answer: “Not so fast! This life is too sweet. It has its own charms.” Worldly esteem, marriage to a wealthy woman and respectable sensuality — enjoying a life like that, he told himself, he might even find a little time to spare for intellectual pursuits.

Through Monica’s efforts, he made a commitment to marry a young woman of good family, but since the girl was underage, their marriage was postponed for two years. He broke with his mistress, and she returned to Africa. But his “disease of the flesh” persisted and he took a new mistress in place of the old, even as he wrestled with theological perplexities about the nature of God. Augustine, in short, was suffering from an affliction not uncommon in super-brainy people — trusting intellect to solve their problems and settle their doubts instead of turning to God and putting themselves unconditionally in his hands.

The impact of St. Paul

Now he took what would prove to be a fateful step — he began reading and reflecting on the epistles of St. Paul. The words of the fiery convert who called himself “the least of the apostles” made a deep impression, and Paul’s praise of continence as a way of life especially struck home. Yet Augustine remained a man of “two wills … one the servant of the flesh, the other of the spirit.”

August of 386 found him staying at a wealthy friend’s country villa with Monica and his close friend Alypius. One day, tormented by questions and doubts, Augustine went into the garden and there, weeping bitterly, flung himself down under a fig tree. Suddenly he heard what sounded like a child’s voice singing the same refrain over and over: “Take it and read, take it and read.”

Augustine describes what happened next:

“I looked up, thinking hard whether there was any kind of game in which children used to chant words like these, but I could not remember ever hearing them before. I stemmed my flood of tears and stood up, telling myself that this could only be a divine command to open my book of Scriptures and read the first passage. …

“I had put down the book containing Paul’s epistles. In silence I read the first passage [in chapter 13 of the epistle to the Romans] on which my eyes fell: ‘Not in reveling and drunkenness, not in lust and wantonness, not in quarrels and rivalries. Rather, arm yourselves with the Lord Jesus Christ; spend no more thought on nature and nature’s appetites.’ I had no wish to read more. … It was as though the light of confidence flooded into my heart and all the darkness of doubt was dispelled.”

Conversion and baptism

Returning to the house, he told Monica what had happened. “She was jubilant with triumph,” he writes, still speaking to God, “for she saw that you had granted her far more than she used to ask in her tearful prayers and plaintive lamentations. You converted me to yourself.”

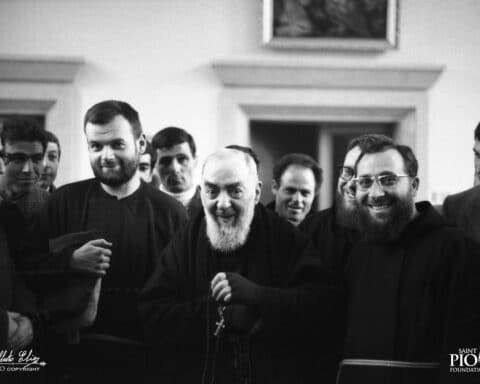

Augustine, Alypius and Adeodatus were baptized the following Holy Saturday. Monica, her dream fulfilled, died in the autumn. Augustine returned to Thagaste, and Adeodatus, who had accompanied him, died not long after. Augustine was living a kind of lay monasticism when the bishop of Hippo persuaded him to be ordained. In 396, he became the bishop’s assistant. The following year he succeeded him as bishop of Hippo.

During the next three decades, along with pastoral duties, he wrote prolifically, composing a stream of theological and scriptural studies as well of thousands of letters and homilies. On Aug. 28, 430, with Vandal warriors besieging his city, he died.

Augustine’s two greatest literary achievements are the “Confessions” and the massive “City of God,” a fundamental text during the Middle Ages that is still read with appreciation. But “Confessions” occupies a unique place as the first true autobiography — a gripping account of the struggle of a man of genius with intellectual pride and deep-seated lust before the turning point at which he placed himself unreservedly at God’s service.

Russell Shaw is a contributing editor for Our Sunday Visitor.