In the title of a 2020 article in The New Yorker, journalist Paul Elie asked, “How Racist Was Flannery O’Connor?” The question-begging title was intentional. In his blunt and brutal essay, Elie left no room for any discussion of whether O’Connor was guilty of the vile sin of racism. In his mind, the only issue is what aggravating factors we should consider in condemning O’Connor and her art as incorrigibly racist. Nor should any mitigating factors be considered. Attempts by her defenders to contextualize racist themes and statements in her stories and letters, he argues, are mere rationalizations; attempts to defend what cannot be defended.

Elie’s article precipitated many reactions from O’Connor’s supporters and detractors alike. Among the former was Jessica Hooten Wilson, who replied to Elie with a carefully qualified essay in First Things, entitled, “How Flannery O’Connor Fought Racism.” Wilson took Elie to task for his misreading of some of O’Connor’s fiction (most notably her story, “Revelation”) and some of her letters, especially to O’Connor’s long-time epistolary friend and intellectual foil — Maryat Lee. While not dismissing O’Connor’s shortcomings — even her sins — Wilson pointed out that O’Connor’s thoughts on race and race relations contain nuance that Elie ignores or fails to acknowledge. Indeed, Wilson persuasively argued that some of O’Connor’s stories — including “Revelation” — are indictments of racism, rather than participants in it.

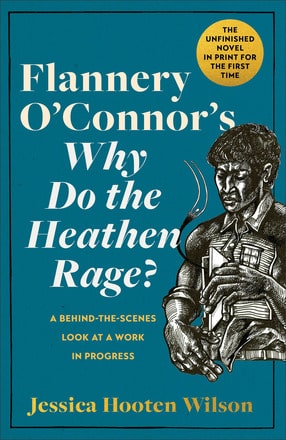

Wilson dives more deeply into O’Connor’s intellectual and artistic struggle with race and racism in her important new book, “Flannery O’Connor’s Why Do the Heathen Rage: A Behind-the-Scenes Look at a Work in Progress” (Brazos Press, Jan. 23, 2024). Along the way, Wilson also considers the problem of attempting to predict the direction of an artist’s work from unfinished fragments and sketches. Neither are simple tasks.

Not an ‘unfinished novel’

It is important to note that Wilson’s book is not the publication of an “unfinished novel” called “Why Do the Heathen Rage?” For this reason, I have a minor quibble with a note on the cover announcing that the book is “the unfinished novel in print for the first time.” There is no unfinished O’Connor novel called “Why Do the Heathen Rage?” Arguably, there’s not even a begun one.

O’Connor was indeed struggling with the idea of a novel by that title, which would have been her third after “Wise Blood” and “The Violent Bear It Away.” And Wilson’s book includes some of the character sketches and discreet scenes that O’Connor may have intended to be part of the new novel. But they are nothing more than that. As Wilson quotes one O’Connor scholar, Marian Burns, the fragments for “Why Do the Heathen Rage?” are “only an untidy jumble of ideas and abortive starts, full scenes written and rewritten many times, several extraneous images, and one fully developed character.” Or, as Wilson herself puts it, “O’Connor left us only a handful of odd scenes.”

In some of these rough sketches, new characters are sometimes substituted for others. At least one important character was made the protagonist in O’Connor’s short story, “Parker’s Back.” And even the “one fully developed character” is borrowed from (or inserted into) at least two other O’Connor stories. In any event, the material is so scant and fragmented, that one cannot even really say that the novel was “begun,” much less that it was left unfinished. There is no narrative arc, nor even an articulated or outlined plan for a plot. And, as Wilson rightly notes, “to publish her unfinished work as a scholarly artifact would be unfaithful to O’Connor’s intentions for the story.”

Having said that, Wilson’s is still an important book, and she has done a service to O’Connor readers in providing us with this brief but penetrating study of an artist struggling to find a particular kind of voice. In short, near the end of her very short life, O’Connor was trying to deal with the problem of race and racial identity in a more direct way than she has previously done in any story or the two novels.

O’Connor’s ‘blind spots’

Wilson reconstructs O’Connor’s attempt — and failure — for a white southern novelist to write a story from the standpoint of a Black character. O’Connor’s inability to finish the novel may have more to do with her short life than her literary or moral imagination. But Wilson demonstrates that O’Connor was not merely struggling with a novel, but deep questions of race and racism that haunted the south in the early 1960s.

The chief protagonist of the projected novel is a young white man, named Walter, who deceitfully poses as a Black house servant in a series of letters to a white civil rights activist. In one scene, O’Connor brings the two characters to the verge of meeting one another — and thus betraying Walter’s deceit. But she does not finish the scene. And in no other fragment do we get any indication whether they did meet, or if Walter’s deception was exposed.

Wilson skillfully reads this unfinished business as something of the struggle with confronting race and racism in O’Connor’s own mind. Wilson does not leave O’Connor off the hook. She suggests that O’Connor perhaps had “too many blind spots, too many missing pieces, too little time to reflect on rather than parody her characters.” She continues, “O’Connor appears to write for white readers without imagining Black readers.” And when she writes of Black characters, “O’Connor fails to envision their perspective and does not try to enter their minds.”

The scenes and fragments included in the book are laced together by Wilson’s own extensive commentary, based upon her exhaustive knowledge of O’Connor’s stories, letters and essays. And to her credit, Wilson frankly acknowledges her own moral risk even in publishing this book in the way she has. “Any work that brings O’Connor’s unfinished ideas before readers will be presumptuous,” she confesses. “We know little of her hopes and aspirations” for the proposed novel; “even less can we step into her shoes and revise it as she would have preferred.”

Wilson’s project is a risky one, in other words, and she approaches it with the proper measure of humility and caveats. In making choices about what to include and omit, she leaves herself vulnerable to trying to shape O’Connor a certain way. But I am glad she took the risk, because she shows O’Connor not only as an artist struggling to create a story, but as a moral agent struggling to live a life.