(OSV News) — A candidate for sainthood who emerged from slavery to become a successful businessman known for his generosity toward others “has many things to offer the ordinary man and woman,” said a champion of his cause.

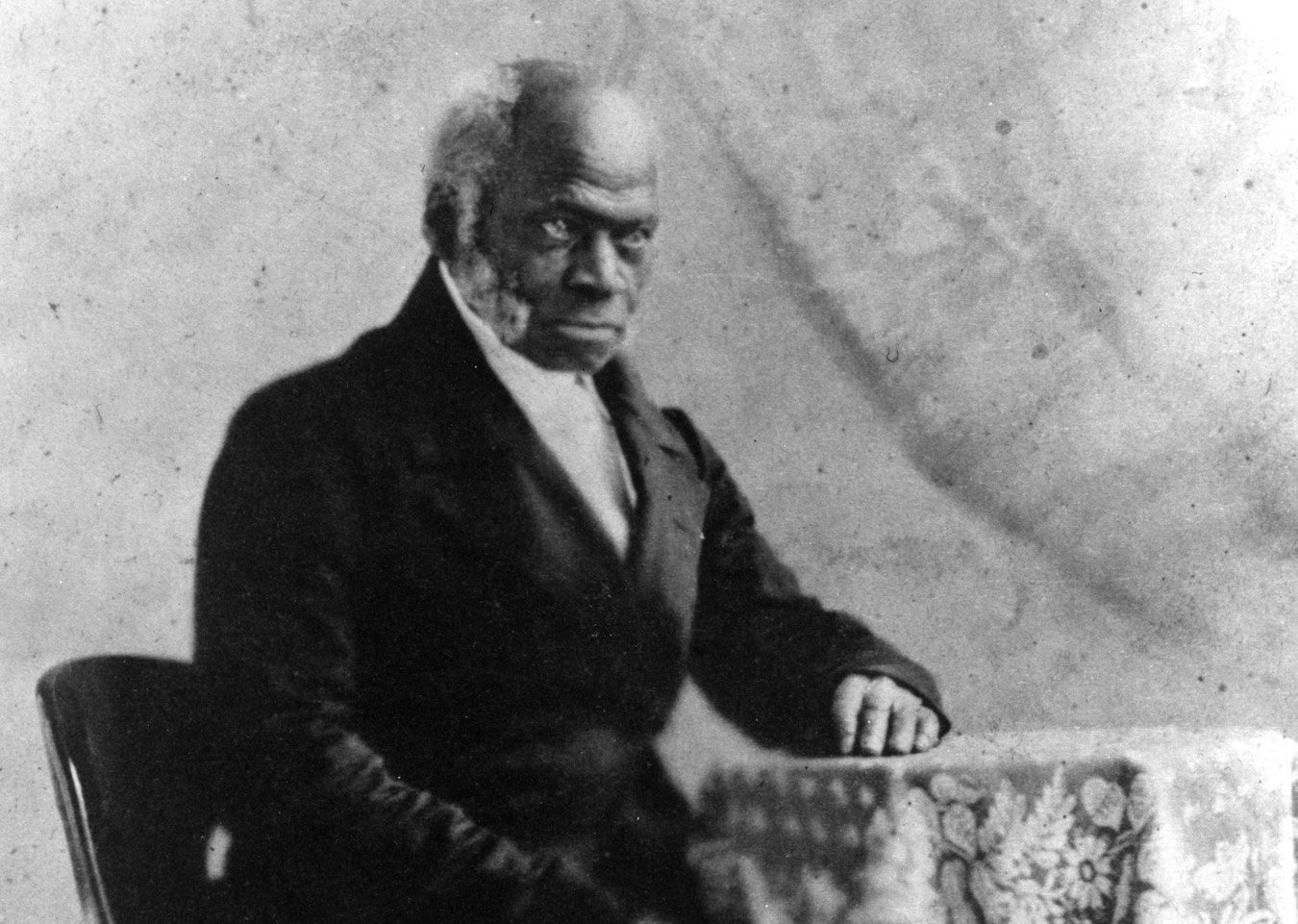

Pierre Toussaint, declared “venerable” in 1997 by St. John Paul II, was born into slavery in St. Mark, Haiti, (then known as the French colony of Saint-Domingue) in 1766 and died a free man in New York in 1853.

Some 170 years after his death, Toussaint — a husband, entrepreneur, philanthropist and above all a man of deep faith — continues to provide inspiration to Catholics, especially laypeople, said Christian Brother Tyrone A. Davis, director of the Archdiocese of New York’s Office of Black Ministry, which is home to Toussaint’s canonization cause.

“To some extent, there is a danger that the vast majority of the faithful see a life of holiness as something that is not meant for them, but rather that it’s the priests and religious who are meant to be the saints,” Brother Tyrone told OSV News. “And the reality is that we’re all called to be saints.”

Trained as a hairdresser

Toussaint, a Black Catholic layman who trained as a hairdresser upon moving to New York with the family he was enslaved to, “worked and struggled and was determined to be good at his craft,” said Brother Tyrone.

Most of Toussaint’s clients “were white women of means, and they grew in their respect for him, and in their respect for the church by way of him,” Brother Tyrone said.

“Some of the pleasantest hours I pass are in conversing with Toussaint while he is dressing my hair,” recalled one client quoted in an 1854 memoir of Toussaint written by Hannah Farnham Sawyer Lee.

Toussaint cultivated the faith instilled in him by his grandmother, Zenobe Julien, and found ways to share that faith with all he encountered, said Brother Tyrone.

“He had a lot of time with his clients, and what he did with that time was evangelize,” Brother Tyrone said. “Those women to whom he tended learned more from him about faith and about Scripture than they probably learned from anyone else. And so obviously Pierre understood that hairdressing was a means to his holiness, but it also was also an opportunity to help someone else along the way.”

A life of freedom and compassion

Toussaint’s compassion also extended to the very family whose slave he had been. He financially assisted the widow who owned him (and freed him upon her death) after she lost her fortune and faced enormous debts. As her health waned, Toussaint proved a wise, compassionate confidant — a witness that prompted one friend to describe him as “a Catholic, full in the faith of his church … always acting from the principle that God is our common Father, and mankind our brethren.”

Upon Toussaint’s freedom, he did not take the surname of his former owners. He chose for himself the surname Toussaint — a name made particularly famous by Toussaint L’Ouverture (1743-1803), a devout Catholic, military-political leader and father of Haiti’s revolution, which overthrew slavery and led to Haiti’s independence from France by 1804.

Pierre Toussaint also purchased the freedom of both Rosalie, his sister, and Juliette, his future wife, whom he married in 1811. He and Juliette later adopted her orphaned niece, and dedicated themselves to numerous charitable efforts throughout their lives — raising funds for a Catholic orphanage, launching New York’s first Catholic school for free Black children, supporting the Oblate Sisters of Providence and helping to pay for the building of Old St. Patrick’s Cathedral in Lower Manhattan.

Strengthened by the Eucharist

Amid a yellow fever epidemic, Toussaint chose to remain in New York and care for the sick and the dying.

“He had the means to be able (to flee), but he chose not to,” said Brother Tyrone. “He didn’t run away … (but) remained committed. And we know people today who went to work during the height of the COVID pandemic. … So even that (aspect) is another opportunity that (modern) people have to connect with Pierre.”

Toussaint — whose philanthropy led him to be dubbed by some as the father of Catholic Charities in New York — was ultimately “nurtured at the Eucharist,” said Brother Tyrone. “He was a regular Mass attendee.”

Strengthened by the Eucharist, Toussaint possessed a spirituality “that was grounded in the ordinary tasks of life,” Brother Tyrone said.

“It was a spirituality that had at its center the life that God gives us, and the life that we give to one another and share with one another,” he said. “So it was very much a life-driven spirituality.”

Now buried in the crypt at St. Patrick’s Cathedral in Manhattan — the only layperson to be so honored — Toussaint continues to invite others to life in Christ, said Brother Tyrone.

“The beauty of Pierre being there is another lesson for people. … Here is a Black man, a layman, who is buried in the crypt under the main altar of St. Patrick Cathedral,” he said. “If that does not tell you that you belong, then I’m not sure what else can do that. Who else can take that away from you?”