Mapping the spiritual journey of C.S. Lewis doesn’t mean finding that one, special turning point at which he declared himself a believer — that’s clear enough — but tracing the long series of events that led up to it. Fortunately, like St. Augustine writing his Confessions centuries earlier, Lewis himself provides a detailed itinerary of the steps that finally brought him to the point of saying, “I believe.”

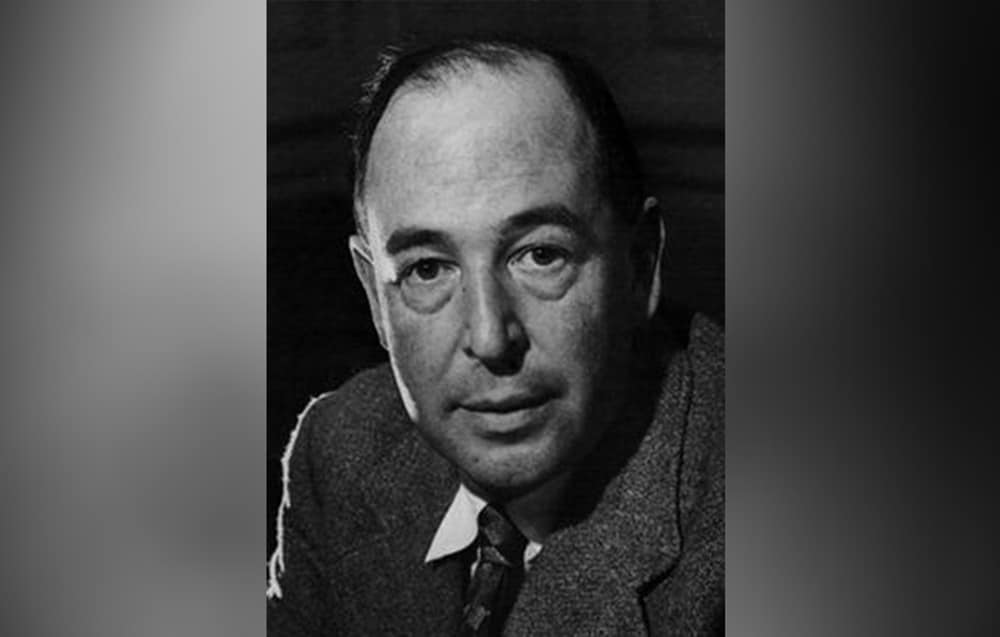

Lewis is remembered today as a writer and Christian apologist — arguably the finest of the 20th century. He was not only a prolific writer but remarkably diverse, with an output that included children’s books, scholarly volumes, science fiction, works on Christian doctrine and a moving, intensely personal account of his grief-ridden quarrel with God after his wife’s death.

His books have been adapted for stage, screen and television, and he has been the subject of several biographies. While there is no telling how many people he has reached, the number clearly is in the millions. But his emergence as a Christian writer was long in coming. In “Surprised By Joy,” the autobiographical story of his conversion, he provides a careful, candid explanation of how he “passed from atheism to Christianity.”

Early life

Clive Staples Lewis was born Nov. 29, 1898, in Belfast, Northern Ireland, the second of two sons of well-to-do parents with bookish tastes and a weakly Anglican religious attachment. On three occasions as a child, he experienced an intense desire for something — what, he couldn’t tell — that he calls “Joy” and that remained embedded in his memory. But with his mother’s death from cancer in 1905, he writes, “all settled happiness, all that was tranquil and reliable” vanished from his life.

Three years later, his father, a successful lawyer, sent him to an English boarding school — a “vile” place, Lewis calls it — where he adopted High Church Anglicanism as his religion. This was followed by a second boarding school, which Lewis liked much better and where, “with the greatest relief,” he stopped being a Christian. The reasons included a bout of scrupulosity, early interest in the occult, loss of belief in the antiquity of Christianity, and at age 14, a “successful assault of sexual temptation.” Under the influence of a favorite teacher, he became “a converted Pagan living among apostate Puritans.”

He also acquired a taste for the music of composer Richard Wagner and for the Nordic mythology that provides the story line for several Wagnerian operas. “Sometimes,” he remarked,

“I can almost think that I was sent back to the false gods … to acquire some capacity for worship against the day when the true God should recall me to himself.”

The next stop was an English public school that disgusted Lewis by its emphasis on achieving and retaining high social status. Needless to say, he remained an atheist, although one plagued by contradictions: “I maintained that God did not exist. I was also very angry with God for not existing.” To prepare him for Oxford, his father next sent him to a retired headmaster, William T. Kirkpatrick, who proved to be an excellent though idiosyncratic tutor, as well as an atheist of what Lewis describes as an old-fashioned “rationalist” variety. Without any overt effort, he gave the boy “fresh ammunition” for his lack of faith.

Having become an atheist and a materialist with a reviving interest in magic and the occult, Lewis — in what he calls “one of the worst acts of my life” — now allowed himself to receive confirmation and first Communion “in total disbelief” so as to avoid having to explain his situation with his father. This was typical of his relationship with a parent who, while wishing to a good father to his sons, was too absorbed in his own ideas and prejudices to have real understanding of them.

Career at Oxford

In 1916, with World War I underway, Lewis entered Oxford with his sights already set on the army. After an officer training course, he found himself on his 19th birthday arriving as a second lieutenant in the trenches in France. During an assault the following April, he was seriously wounded by a British shell that fell short of its target.

A brilliant postwar academic career at Oxford followed. As always, he read widely. Among the authors who impressed him were the Scottish fantasy writer George MacDonald, Catholic essayist and novelist G.K. Chesterton and French philosopher Henri Bergson, whose work persuaded him to abandon materialism in favor of idealism and led him to believe, if not precisely in God, then at least in “the absolute.”

Battle for God

Reflecting on this period of his life, he issues a tongue-in-cheek warning: “A young man who wishes to remain a sound atheist cannot be too careful of his reading.” For now, he made the disconcerting discovery that all his favorite authors, past and present, were religious while the non-believers were “thin.”

After graduation, Lewis taught at Oxford. There he became one of the Inklings, an informal group of literary men who met for conversation and the reading of one another’s works-in-progress. Along the way, Lewis read Chesterton’s “The Everlasting Man,” finding there a persuasive Christian vision of history. Now, too, the “hardest boiled” atheist he’d ever known rattled him by remarking that “the evidence for the historicity of the Gospels was really surprisingly good.” And fellow Oxford professor and Inklings member J.R.R. Tolkien, a Catholic and future author of “Lord of the Rings,” began encouraging him to convert.

To believe, or not to believe

Eventually, he realized that he was facing a choice: whether to believe or not. Lewis writes: “In the Trinity Term of 1929 I gave in and admitted that God was God, and knelt and prayed: perhaps, that night, the most dejected and reluctant convert in all England. … The hardness of God is kinder than the softness of men, and His compulsion is our liberation.”

But there was still one step remaining to be taken — the final turning point in a long journey. One sunny morning in 1931, Lewis and his brother, Warren, decided to visit Whipsnade Zoo, a popular 600-acre zoo and safari park in Derbyshire. Lewis tells what happened: “When we set out I did not believe that Jesus Christ is the Son of God, and when we reached the zoo I did. Yet I had not exactly spent the journey in thought. Nor in great emotion. … It was more like when a man, after long sleep, still lying motionless in bed, becomes aware that he is now awake.”

Lewis became, and was to remain, a conservative Anglican with traditional theological views. After teaching at Oxford for 29 years, in 1954 he became first holder of the chair of medieval and Renaissance literature at Cambridge University. Two years later, he married Joy Davidman, an American woman who had divorced her abusive husband. In a book called “A Grief Observed,” he recorded his painful struggle to accept God’s will after her death in 1960.

Besides scholarly works, his books include an immensely popular series of children’s stories set in an imaginary land called Narnia, three science fiction novels, “The Screwtape Letters,” an analysis of the psychology of temptation cast in the form of letters from a senior demon to his nephew, and “Mere Christianity,” perhaps the best known of his several works of popular theology and apologetics.

Lewis died of kidney failure on Nov. 22, 1963, the day President John F. Kennedy was assassinated. In 2013, he was honored with a place in Poets’ Corner in Westminster Abbey. The spot is marked by a Lewis quote: “I believe in Christianity as I believe that the Sun has risen, not only because I see it but because by it I see everything else.”