“Loyalty to the white race, to the traditions of America, and to the spirit of Protestantism … has been an essential part of Americanism ever since the days of Roanoke and Plymouth Rock.” Hiram Wesley Evans, the imperial wizard of the Ku Klux Klan, offered this definition of Americanism in the pages of North American Review, the oldest literary magazine in the United States, in 1926. The sentiment can be traced to the founding of the English colonies. To be American was to be white, Anglo Saxon and Protestant.

Many Americans believed Catholics were, at best, incapable of being truly American and, at worst, a threat.

Many Americans believed Catholics were, at best, incapable of being truly American and, at worst, a threat because their religion was superstitious, suppressed personal liberty and required loyalty to a foreign leader (i.e., the pope) who was hostile to Protestantism at home and abroad. In a country whose founding was shaped by both the intellectual Enlightenment and the religious movement known as First Great Awakening, Catholics could not be true citizens. Many leading figures and movements in the first 125 years of the nation’s history believed and acted on this belief, but the KKK embodied the most virulent and aggressive form of this hatred nationwide.

Fighting Catholic immigration

When most of us think of the Klan, we are thinking of it as an organization with a thru-line all the way back to 1865, but the truth is that the first iteration of the KKK was short-lived. Historian David Chalmers explains that it began as group of former Confederate soldiers who amused themselves by pretending to be ghosts with silly titles before evolving into something far more terrible when they realized their antics scared recently freed Blacks. It ultimately became a terrorist group intended to restore white supremacy in the South before being put down by President Ulysses S. Grant’s administration and the military in 1872.

On Thanksgiving Day 1915, William J. Simmons founded the second iteration of the Ku Klux Klan at Stone Mountain, Georgia. This former preacher turned salesman resurrected the ideals and methodology of the first Klan and combined them with made-up imagery from D.W. Griffith’s recent blockbuster film, “The Birth of a Nation,” which valorized them. When Simmons observed the nationwide tension over the question of immigration, he saw an opportunity for his organization ripe for the taking.

Americans’ concerns about immigration had grown as two massive waves of Catholic immigrants arrived in the United States over a period of 80 years, beginning in the 1840s. As Josh Zietz writes, “Until the 1920s, America’s doors were open to European immigrants, as long as they qualified under a statute passed in 1790 that reserved naturalized citizenship for ‘free white persons.'” The first wave consisted of Irish and German immigrants who swelled the ranks of Catholics in the United States by the millions prior to the Civil War. The second wave came between 1890 and 1924 and was even bigger, with most of the new arrivals coming from southern and eastern Europe and settling in eastern and midwestern cities.

Immigrants did not necessarily come to America with the aim of changing American culture (they came for simpler reasons), but change it they did.

Immigrants did not necessarily come to America with the aim of changing American culture (they came for simpler reasons), but change it they did. Most Americans believed their country was a white, English-speaking, Protestant country whose way of life was rooted in agrarian rhythms. This new wave of immigrants was mostly Catholic and Jewish, the majority did not speak English, had customs and loyalties that seemed odd, and made cities politically powerful at the expense of rural areas. Consequently, religious, ethnic and political tensions were combined into anti-Catholic sentiment. Senator Ira Hersey of Maine was hardly unique in complaining in 1924 that “we have thrown open wide our gates and through them have come other alien races, of alien blood, from Asia and southern Europe … with their strange and pagan rites, their babble of tongues.” His implication was clear: These people, including Catholics, could not be good Americans.

Hatred and suspicion increases

Although William Simmons believed anyone who wasn’t a white, Anglo-Saxon Protestant was a menace to the United States, his primary motivation was to create a fraternal organization that would make him rich by means of members’ dues. He was not successful at growing the Klan, however, and membership remained small and restricted to the South until 1920.

At that point, two things happened that led to the Klan’s explosive growth. First, Simmons was given a ready-made target with which to drum up fear: the national Red Scare that followed the end of World War I. Worried about the Communist revolution that created the Soviet Union, Americans had exchanged their hatred of Germans for hatred of politically radical immigrants. In 1919 and 1920, the situation came to a head with radicals mailing bombs to government officials, the most labor strikes in one year in American history and the arrest of Italians Nicola Sacco and Bartolomeo Vanzetti in Massachusetts for murder. Unfortunately, the most high-profile radicals came from eastern and southern Europe, the same place as most of the recent Catholic arrivals. As the summer of 1920 passed without major strikes or bombings, the Red Scare began to abate, but hatred and suspicion of immigrants did not. In the minds of many, anti-American and Catholic were as connected as ever.

Simmons understood the fears of the people he was trying to take advantage of, but his most brilliant move was to hire the Southern Publicity Association from Atlanta, owned by Edward Young Clarke and Mary Elizabeth Tyler, clever marketers who capitalized on the hatred and fear permeating the country. The publicists offered an aggressive new way of selling the Klan: that it would be fiercely pro-American, which to them meant rabidly anti-Black, anti-Catholic, anti-Jewish, anti-labor, anti-wet, and anti-immigrant of any kind. The organization would be suspicious of other transformations in the country as well, including big business and changing sexual norms.

The message resonated, but their true brilliance lay in the pyramid scheme set up of the new Klan. At the time, the initiation fee was $8, or roughly $122 dollars in 2023. Clarke and Tyler themselves would receive 80% of the initiation fee for every new member, which allowed them to create a pyramid of recruiters (or “Kleagles”) across the country with “King Kleagles” overseeing recruiting in each state, all of whom would get a cut of new members’ (“Ghouls”) fees. Those at the top of the pyramid became rich, including the leader of the Klan in Indiana, David C. Stephenson, who became one of richest and most powerful men in the state. Fees were not the only way Klan leaders profited off their members; Ghouls could only buy their robes and other paraphernalia from the Klan itself. It was a tremendously successful, if cynical, money-making scheme that played on old fears.

Getting away with murder

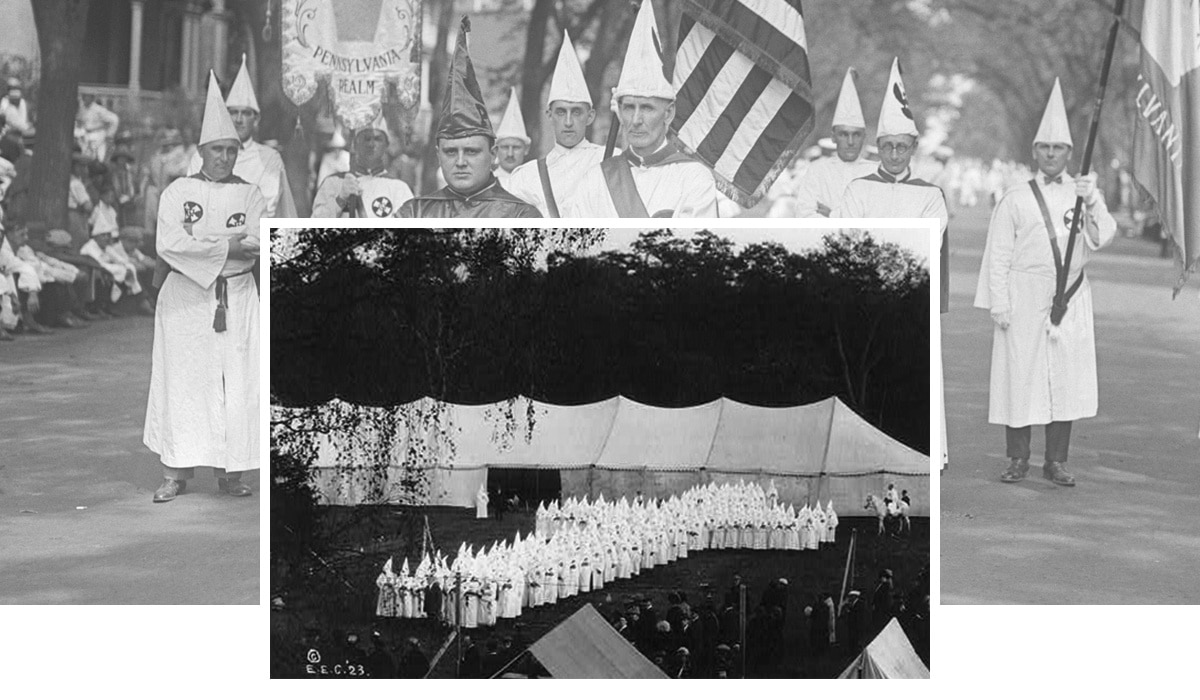

The new Klan grew like wildfire in the early 1920s. It spread far beyond the South as far northwest as Oregon and northeast as Maine, but surprisingly, given our modern mythology, the greatest number of members was in the Midwest: Ohio, Indiana and Illinois. Unlike previous and later versions of the Klan, this one grew in cities, as well. The most reliable estimates suggest that at its height there were as many as 4 million members of the Klan, or 15% of the eligible population. During the decade, it even exercised great power at the ballot box, helping to elect governors and congressmen in every region of the country except the Northeast.

Although some people joined out of a sense of civic obligation or desire to strengthen business connections, too many members across the nation took seriously the incendiary rhetoric that incited violence and division in their communities. The claims may have been made by insincere recruiters interested primarily in money, but they had very real consequences for Blacks, Catholics and others who were targeted. The KKK used arson, lynching and boycotts to intimidate its victims. Like the lies drummed up against Blacks, the Klan attacked priests and nuns as diabolical creatures. It even threatened Catholic universities, such as Notre Dame, the University of Dayton and Regis University.

The KKK used arson, lynching and boycotts to intimidate Catholics. Like the lies drummed up against Blacks, the Klan attacked priests and nuns as diabolical creatures.

The average member may not have been involved in violence, but the Klan’s numbers gave it political influence, and their money made it rich. The Klan could do as it wished, at least for a little while. It literally got away with murder, as the 1921 shooting of Father James Coyle demonstrates. Father Coyle was an Irish priest who was not afraid to combat Klan lies about the Church in the Birmingham, Alabama, press. He also baptized Ruth Stephenson, daughter of Southern Methodist Episcopal minister and Klansman, Edwin Stephenson, into the Church. Months later, Father Coyle celebrated Ruth’s marriage to a Puerto Rican Catholic named Pedro Gussman. Hours later, Stephenson found Father Coyle reading his breviary on the porch of his rectory and shot him three times, killing him. In the ensuing trial, Stephenson was defended by Hugo Black, a future member of the Ku Klux Klan and eventually a Supreme Court justice, and tried by a Klansman judge and an all-white jury. Despite there being no question that Stephenson had killed Coyle, he was acquitted based on a claim of temporary insanity.

| ‘Regarding the Ku Klux Klan’ |

|---|

|

Excerpt from an editorial by Father John Francis Noll, founder of Our Sunday Visitor, Aug. 21, 1921 The consensus of public opinion, as represented by the Press, is quite plain. The Klan is not wanted. It is regarded as unnecessary. It is regarded as thoroughly un-American, not only because of its assumption of the functions of the judicial machinery of the State, but also of the utter lack of responsibility which its secrecy protects. Its activities are denounced as outrages. Its members, and especially its flamboyantly titled officers, are invited to strip off their masks and come out in the open. And all this quite independent of the fact that the newspapers, for the most part, do not especially notice the anti-Catholic aspect of the organization. But there can hardly be any doubt that at bottom the Klan is nothing more nor less than a recrudescence of the old A. P. A. [American Protective Association] dressed up in white masks and with an organization of officers who, as Imperial Wizards and Kleagles and what-not of an “Invisible Empire” enroll their subjects (we had almost written “dupes”) in a citizenship, the regulations of which, being secret, can only be judged by the lawless and un-American actions which result from it. What the outcome of the Klan movement may be it is too soon to say, but Catholics may rest assured that the sober common-sense, and the deep underlying sense of justice, which are characteristics of the American people, will not endure indefinitely the situation which these nameless bigots seek to impose upon the country. |

Political victories

There were political ramifications, as well, particularly in states where the KKK controlled the government. The Compulsory Education Act requiring all children in Oregon to attend public school was the most famous example. Education had long been a point of contention between Protestants and Catholics in the United States, and it became the focal point of the Klan’s crusade to “Americanize” Catholic immigrants in Oregon. The bill never explicitly mentioned Catholic schools, but it clearly targeted them by preventing children from attending private schools. The Klan submitted their bill directly to the public in a ballot initiative in 1922. To the surprise of many observers, Oregonians approved the bill.

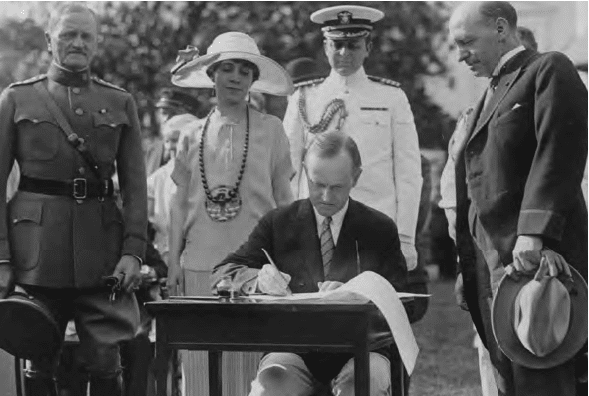

The first half of the 1920s saw other political victories for the Klan. The group managed to throw the 1924 Democratic National Convention into disarray by opposing Al Smith, the governor of New York, who was the Catholic son of immigrants and opposed to prohibition. At the same convention, it prevented adding a denunciation of itself to the party’s platform. Most significantly, 1924 saw the passage of the Immigration Act, which beginning in 1929 would limit the annual number of immigrants who could be admitted from any country to 2% of the number of people from that country who were already living in the United States in 1890. The bill essentially ended immigration from Southern and Eastern Europe because few people from those areas had arrived in America by 1890, which meant Catholic immigration stopped as well. Immigration from Asia and Africa was completely banned. With the support of Congress and the White House, the Klan’s ultimate goal had been accomplished.

Catholics fight back

Catholics did not passively accept the Klan’s attacks. They combatted its influence in the press, in the courtroom and at the ballot box. They told the truth over and over, usually calmly. When the Klan published a falsehood in a magazine or local newspaper, countless clergy and laypeople insisted on running a piece countering it. Jesuit Father Martin Scott, a professor at the College of St. Francis Xavier, rebutted Imperial Wizard Evans’ North American Review essay — cited in the opening paragraph of this article — in the following issue. Father Coyle had done this in Alabama, as well as attending to the sacramental life of his parishioners, even when he knew it might cost him his life. Indeed, it was later noted that Father Coyle’s murder created a “revulsion among the right-minded” in Alabama, diminishing the Klan’s influence there for the rest of the decade.

The Denver Catholic Register, edited by Father Matthew Smith, and the Georgia Laymen’s Association were particularly effective as well. The organizations never attempted to appeal to Klan members; instead, they were trying to appeal to reasonable people who could be persuaded. Father Smith and others were also clear-eyed about the profit as a primary motive for Klan leadership, routinely referring to them as money grabbers and accusing them of selling their souls for money. Holy Cross Father Arthur Hope, in describing the fight between the Ku Klux Klan and Notre Dame students, neatly summarized the former as “a campaign of hate for the purpose of raising money.”

Catholics did not passively accept the Klan’s attacks. They combatted its influence in the press, in the courtroom and at the ballot box. They told the truth over and over, usually calmly.

Catholics saw some of their greatest success combating the Klan through the legal system. After the passage of the Compulsory Education Act in Oregon, Archbishop Alexander Christie of Portland enlisted the National Catholic Welfare Conference’s (the forerunner of the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops) support in challenging the constitutionality of the law. In December 1923, lawyers for the archdiocese filed an injunction against the law on behalf of the Sisters of the Holy Names of Jesus and Mary, who oversaw multiple schools in Oregon. The archdiocese won a series of cases, culminating with the Supreme Court decision Pierce v. Society of Sisters in 1925 that overturned the law and guaranteed the right of private schools to exist.

Catholics were less successful politically: Hundreds of candidates who were supported by the Klan or were Klansmen themselves were elected to local and state offices in the first half of the 1920s. Catholics and other allies against the Klan had a little more luck at the national level. Al Smith may not have been the Democratic presidential candidate in 1924, but his supporters prevented the Klan from nominating its preferred candidate, William McAdoo.

The Klan falls apart

Ironically, at the very height of the second Ku Klux Klan’s success, the movement began to fall apart due to the hypocrisy, hate and greed at its core. Father Smith of Denver described the Klan’s demise with startling accuracy in a 1924 article. In it, he explained how important it was that Catholics take an active role in presenting the truth about the Church to Americans and avoiding violence, which would turn Klansmen into victims. Catholics did this admirably during the 1920s. At the same time, Smith forecasted that the Klan could not last because it was “founded on hate” and “built on principles which must inevitably bring discord among its own members.” Over the next few years, the Klan proved him right.

Americans began to desert the Klan as its inner workings were made public and the personal immorality of its leaders was exposed. Lawsuits and internal struggles between William Simmons, Hiram Wesley Evans and David C. Stephenson played out in the press, undermining claims to the Klan’s moral authority and making clear how central pursuit of profit was to their enterprise. The press also exposed conduct counter to the traditional Protestant values it claimed to uphold. Clarke and Tyler, the publicists so effective in growing the Klan, were forced out of the Klan for drinking and financial and sexual misconduct. More significantly, David C. Stephenson, perhaps the most charismatic and the most politically powerful of the national Klan leaders, was arrested and convicted in 1925 after kidnapping and raping a young woman who had worked for the Klan who then committed suicide. Stephenson’s conviction, combined with growing publicity around the Klan’s violent activities, made it increasingly difficult for the average member to believe the Klan was a bastion of patriotism and traditional Christian values.

There was one other important, disappointing reason for the second Ku Klux Klan’s demise: it was a victim of its own success. What tied together so much of the Klan’s hatred for a variety of ethnic and religious groups was its opposition to immigration. The passage of the Immigration Act of 1924 and the practical end of overseas immigration to the United States for the next 40 years meant it had succeeded and was now robbed of its primary reason for being.

Shrewd as serpents, simple as doves

The Klan held on for a few years, most famously demonstrating its power with a parade down Pennsylvania Avenue in Washington, D.C., in 1925, but its influence waned quickly. It could not stop the presidential nomination of Irish Catholic Al Smith in 1928, and six of the eight states Smith carried were in the Deep South. Membership fell almost as quickly as it had risen, withering from 4 million in 1924 to 30,000 in 1930. The Klan receded into the rural South with some klaverns in the rural Midwest. It eventually ceased to exist as a national organization in 1944 after being successfully prosecuted for failure to pay federal taxes, but the hateful ideology never fully disappeared. People’s fear of the other remained, as did people’s willingness to exploit that fear to make a buck. The Ku Klux Klan would remain dormant until the third version emerged in the 1950s and 1960s. This version returned to the Klan’s anti-Black roots, opposing the Black civil rights movement. The group did not quite leave behind anti-Catholicism, occasionally threatening Catholics, particularly if they supported the civil rights movement. Sadly Southern Catholics’ record was mixed on that front.

In this moment of social upheaval, the examples of Catholics who dealt with the Klan can be instructive. They embodied Christ’s admonition to the disciples in Matthew 10:16 to “be shrewd as serpents and simple as doves.” In countering the Klan’s campaigns and propaganda, they saw the racket. They knew this was cynical, hateful nonsense intended to profit off of people’s fears. They also knew that it could have real consequences: Father Coyle and others were attacked, businesses were destroyed, immigrants (including European Jews fleeing Nazi persecution in the 1930s) were turned away from the United States. These Catholics were faithful and brave enough to state the truth publicly.

As far as being doves, they did this without violence or malice, and often while trying to love their neighbors. It is here that a story relayed by Mark Pattison is particularly useful: “a woman marching at a 1928 KKK rally felt faint and was taken to a nearby house to rest. Upon reviving, she said to her host ‘You’re a Christian, lady, a real Christian; maybe you’re a member of my own church ….’ The unnamed hostess replied, ‘I’m just a plain old woman who tries to do right, but I’ll say this: There is no happier member of St. Patrick’s Church than myself.'”