MEXICO CITY (OSV News) — Mexican electoral campaigns started March 1 for a historic election: The country is likely to elect its first female president as women lead the two main party coalitions.

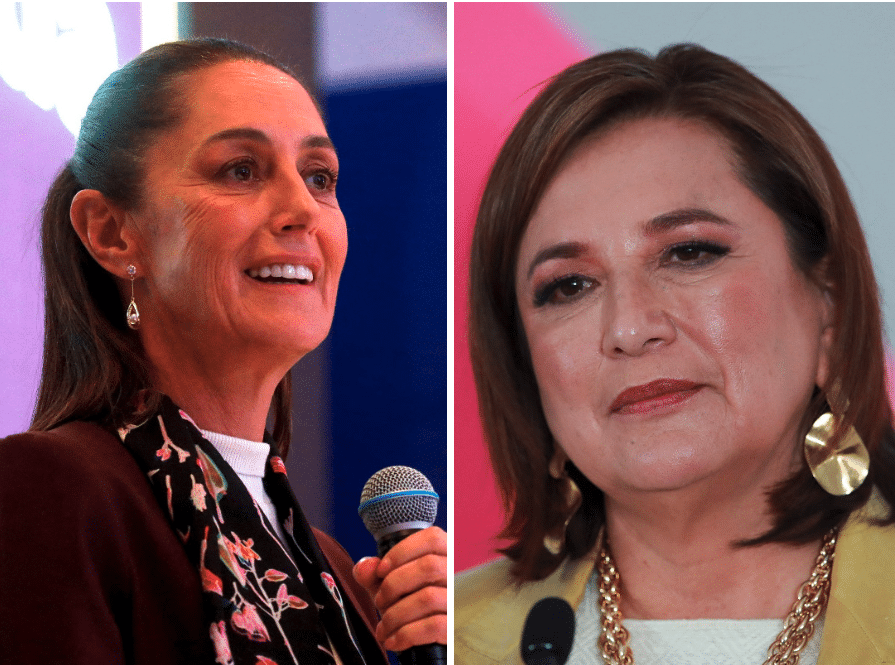

Ruling Morena party candidate Claudia Sheinbaum would become Mexico’s first Jewish president if she wins June 2. Xóchitl Gálvez, candidate for a three-party coalition, is of Indigenous Otomi descent. Jorge Álvarez Máynez of the small Citizen’s Movement party also is on the ballot.

The Mexican bishops’ conference has urged citizens “to actively and committedly participate in the upcoming electoral elections … as a gesture of service, justice and peace.”

But the campaigns are unfolding amid divisions in Mexico, where populist President Andrés Manuel López Obrador — who is constitutionally prohibited from seeking reelection — has overshadowed the candidates running to replace him.

Much of the preelection period has been marked by political bickering and rising violence. Two mayoral candidates were murdered in western Michoacán state Feb. 26, reflecting the increasing incursions of drug cartels into electoral politics.

“This is a completely polarized country,” said Father Raúl Martínez, a priest in the Diocese of Valle de Chalco on the southeastern outskirts of Mexico City.

López Obrador used the preelectoral period to introduce a suite of 20 constitutional reforms, which would allow for the election of supreme court judges, shrink the electoral authority and eliminate the country’ transparency institute.

Citizens from civil society organizations held marches in cities across Mexico Feb. 18 in defense of democracy and against the president’s reforms.

López Obrador responded by lowering the massive flag normally flying over the massive Zócalo main square in central Mexico City — site of the biggest demonstration — and accusing the protesters of defending the democracy of the “corrupt.”

Solidarity with pro-democracy marchers

The bishops’ conference “expressed its solidarity” with the demonstrators, saying in a Feb. 19 statement, “The Catholic Church in Mexico is committed to the consolidation of democracy in the country. We call on all Catholics and citizens in general to become informed on the candidates’ proposals, analyze their governing plans and vote in a free and reasoned way on election day.”

The statement continued, “We hope that the electoral process that is about to begin will be carried out in a context of civility, respect and adherence to the law. Democracy requires reliable institutions and citizens committed to the common good.”

The bishops’ conference did not make a spokesman available for comment. But the statement reflected some of the somewhat distant relationship the bishops have had with López Obrador in comparison to other presidents since Mexico and the Vatican established diplomatic relations in 1992.

“At the official level of the church, there has not been a dialogue where we can sit down to raise issues and look for alternative solutions,” Archbishop Carlos Garfias Merlos of Morelia told OSV News.

Meetings with the pope

Sheinbaum and Galvez met with Pope Francis at the Vatican in February in visits arranged without the Mexican bishops’ participation.

They released simultaneous social media posts afterward. Sheinbaum, who has previously identified as nonreligious, expressed admiration for the pope and tweeted passages from his “Fratelli Tutti” encyclical; Gálvez spoke of the experience deepening her Catholic faith. Both candidates have expressed support for abortion decriminalization, which expanded to the national level after a 2023 supreme court decision.

The Vatican visits revealed the complex role of religion in Mexico’s public life. Issues of faith were considered verboten in Mexican politics until recently. But seeking audiences with the pope reflected the importance of appealing to the Catholic population, which, according to church observers, expects candidates to show a respect for Catholicism but objects to priests and prelates preaching politics from the pulpit.

“Both are aware that the people they aspire to govern are mostly Catholic,” Archbishop Garfias said.

The bishops planned to meet with the three candidates March 4 to sign on to a National Commitment for Peace, “which seeks to propose public policy strategies to stop the painful violence that has left thousands of victims.”

Priests murdered

The proposal follows up on a National Dialogue for Peace convened after the 2022 murders of two elderly Jesuit priests in their parish church in the rugged Copper Canyon in the mountains of northern Mexico. López Obrador rebuked the bishops afterward for urging him to reconsider his “hugs, not bullets,” security policy.

Jesuit Father Jorge Atilano, who participated in the dialogues, told OSV News that he hears “concern” from people ahead of the elections. “There is more control by criminal groups” over daily life in parts of Mexico and “involvement of these groups in the elections,” he said. “Campaigns haven’t even properly started and the first candidates are being killed.”

Polls show Sheinbaum entering the race as the frontrunner; a survey in the newspaper El Financiero gave her a 16-point advantage over Galvez.

A climate scientist and former mayor of Mexico City, Sheinbaum has promised to continue López Obrador’s policies such as providing cash stipends to seniors, single mothers and students. She also has spoken of expanding the policing model in Mexico City, where crime has fallen over recent mayoral administrations, to the rest of the country.

Her career has been tied to López Obrador from the start, according to analysts, and she has never publicly contradicted the president — even on environmental issues — leaving her presidential agenda somewhat of a mystery.

“(Her) main electoral asset for 2024 is the continuity of López Obrador’s policies,” said Aldo Muñoz, political science professor at the Autonomous University of Mexico State.

Gálvez grew up in an impoverished Otomi Indigenous village, selling tamales to help her family. She won a scholarship to study computer engineering and founded a successful tech company before entering government in 2000 as commissioner for Indigenous affairs. She later became a borough chief in Mexico City and a senator.

Her pre-campaign has sputtered at times with her policy statements shifting from left to right, while her electoral coalition appears rocky, according to analysts as it spans the political spectrum. The opposition also remains unpopular after being beaten badly by López Obrador in 2018 and being full of politicians with checkered pasts.

“She was the best candidate the opposition had,” said Diego Petersen Farah, columnist with the Guadalajara newspaper El Informador. Also working against Gálvez, “Claudia has the state apparatus behind her,” Petersen Farah said. “Xóchitl doesn’t.”