VATICAN CITY (CNS) — The accusation that Christianity is a “foreign religion” in China has been repeated for hundreds of years, and for just as long missionaries and popes have tried to assure the government and the people that a person can be fully Chinese and fully Catholic at the same time.

What is more, for some 700 years the efforts to make the church truly Chinese have drawn criticism; even today, there are critics who accuse Pope Francis of betraying China’s most faithful Catholic communities and the ideal of religious freedom itself by allowing the Chinese communist government to have a say in the appointment of bishops.

Commemoration of the Council of the Chinese Catholic Church

A daylong conference at Rome’s Pontifical Urbanian University May 21 commemorated the 100th anniversary of the Council of the Chinese Catholic Church and kept returning to one of the council’s key points: helping the Catholic community in China transition from being a “foreign mission” to a “missionary church,” as Cardinal Pietro Parolin, Vatican secretary of state, described it.

The Vatican’s current accord with the communist government, forged in 2018 and renewed in 2020 and again in 2022, was alluded to, but not discussed at the conference. Bishop Joseph Shen Bin of Shanghai was one of the speakers at the conference, particularly because the Council of the Chinese Catholic Church was held in Shanghai in 1924.

But Bishop Shen’s appointment to Shanghai in April 2023 marked a low moment in the recent history of Vatican-China relations since the government decided on his transfer without Vatican agreement, apparently in violation of the joint accord. The situation was resolved three months later when the pope agreed to the transfer “for the good of the diocese.”

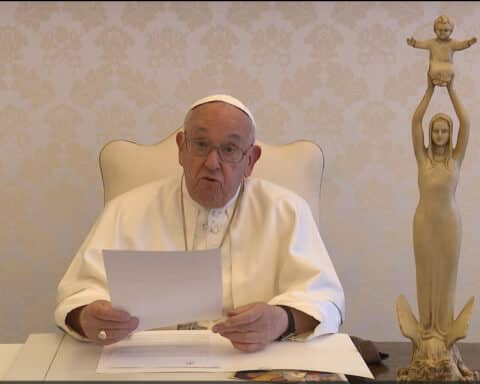

Cardinal Parolin and Pope Francis himself have said that giving up full control over the choice of bishops is not what the Vatican would have hoped for, but it seemed to be a good first step toward ensuring greater freedom and security for Catholics in China, and it was a way to ensure that all the mainland’s Catholic bishops — those recognized by the government and those operating in the more “underground” communities — were in full communion with the pope.

Archbishop Celso Costantini’s vision

In his speech to the conference at the Urbanian University, Cardinal Parolin spoke at length about Archbishop Celso Costantini, the then-apostolic delegate in China, who led the council with the aim of revitalizing the mission of the church in China in light of Pope Benedict XV’s assertion that faith in Christ “does not belong exclusively to a certain nation” and that becoming a Christian does not mean submitting to “foreign tutelage.”

The bishops who participated in the Shanghai council illustrate the problem, as Cardinal Luis Antonio Tagle, pro-prefect of the Dicastery for Evangelization said: There were 17 French, 10 Italian, five Spanish, five Belgian, four Dutch and two German bishops. The two top-ranking Chinese clergy were serving as apostolic prefects, not as the heads of dioceses.

Archbishop Costantini was clear about the need to root Catholicism in Chinese culture, Cardinal Parolin said. “According to him, until then the work of evangelization in China gave the impression of having ‘transplanted’ a tree already developed and full of foliage which, however, had never had the possibility of penetrating its roots into the depths of the soil.”

The first six Chinese bishops were ordained two years after the council and, Cardinal Parolin said, the inculturation of the Catholic faith could not ignore “a fundamental requirement, or rather a necessary and implicit condition, which supported its entire structure: the link with the Successor of Peter. It is no coincidence that the ordination of the first Chinese bishops, who would initiate the indigenous apostolic hierarchy, took place in Rome, in the Vatican basilica and at the hands of the Supreme Pontiff himself.”

Addressing “Westernism” in missionary work

Cardinal Tagle, closing the conference, said the council “took into account the cultural and also political reality of China, then in the midst of change and full of unknowns, and recognized the need to get rid of what Costantini scholars define as ‘Westernism,’ that is, ‘the inclination to transfer all the cultural trappings of Western Christianity to the new churches which were emerging among non-European peoples.'”

“The passion for the proclamation of the Gospel,” Cardinal Tagle said, “led to the recognition that, in the time preceding the council itself, erroneous paths had been taken. The confusion, often experienced, between missionary works and the colonialist strategies of Western powers had been detrimental to the mission.”

In many parts of the world, the arrival of missionaries with foreign explorers and troops led to a situation where anything that made Christianity appear “as a religious banner of external policies and interests fueled distrust, hostility and even hatred toward the church and missionaries,” the cardinal said.

A century of encouraging local clergy and religious in China, demonstrating deep appreciation for Chinese culture and continuing those policies even in the face of hardship and persecution is bearing fruit, Cardinal Tagle said. “I believe that Constantini and so many fathers of the Council of Shanghai would be happy to recognize that today the community of baptized Catholics in China is fully Catholic and fully Chinese.”