Kara is a 32-year-old mother of three. She goes to Mass weekly and has an active prayer life, but lately, she has been struggling emotionally.

“I just feel sad and depleted all the time,” Kara said. “I can’t motivate myself to do anything. I get the kids off to school, and I’ll sit down for a minute and an hour goes by. Thank God I work, or I think I might not get off the couch all day. I’m grumpy all the time. The other day, my daughter, Addy (6), said, ‘Mommy, did I do something wrong?’ I told her she hadn’t. She said, ‘Then how come you’re mad at me all the time?’ I wanted to crawl into a hole and die. I just held her and started to cry. I don’t want to be this person, but I don’t know what to do. I feel like I’m letting everyone down — especially God.”

Mario, 40, is a husband and father of two teenagers. Recently, work difficulties have spiraled into a much larger emotional crisis.

“My new boss has no clue how this company works, but that doesn’t stop him from trying to change everything overnight,” Mario said. “A whole bunch of people I respect have quit recently. I feel like it’s only a matter of time before I have to go, too, but I just hate the idea of starting over somewhere else. All those years I put into this place, it just feels so pointless. I tried to talk to my pastor about it, and he said he’d pray for me. I’m glad, I guess, but I’m not sure God answers my prayers. I feel like I’ve been stuck in this place for so long now. I’m not sure what I’m supposed to believe.”

To cope, Mario has been drinking more, which is increasing the tension between him and his wife. She fears that his behavior is causing him to check out of family life and serve as a bad example to their two teen boys.

“I hate that she thinks that about me,” he said. “But I just don’t know what to do. I hate feeling so down all the time.”

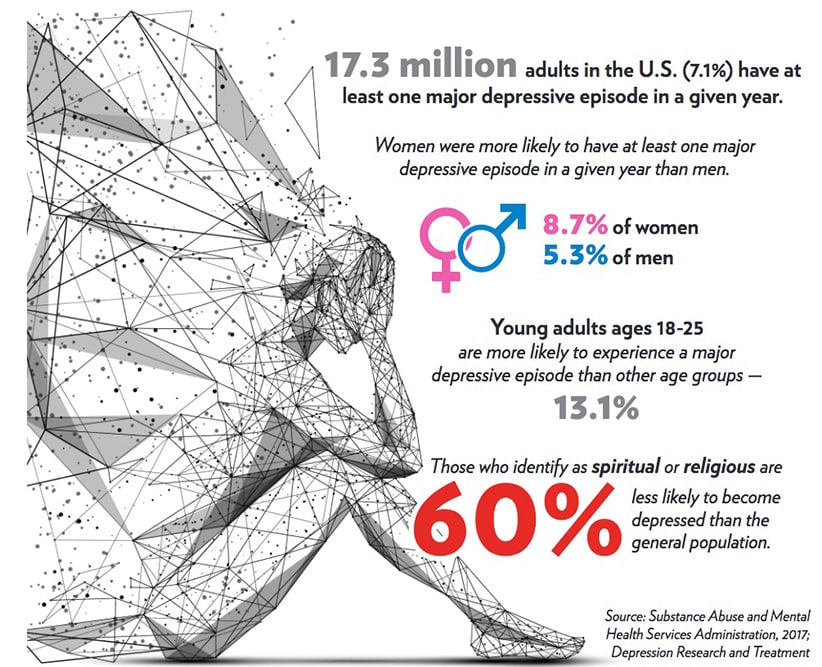

In the United States, more than 16 million adults are diagnosed with some form of depression every year. And those are only the ones who seek help. According to one study by Harvard Medical School, only 1 in 5 depressed adults pursue treatment for depression. That means, in any given year, there could be as many as 80 million people in the U.S. who are experiencing some form of depression with 64 million receiving no treatment whatsoever.

Although there are a range of depressive disorders that run the gamut from burnout and “the blues” to suicidal depression, depression of any type is a serious matter. According to the World Health Organization, depression is “a leading cause of disability worldwide and is a major contributor to the overall global burden of disease.”

What is depression?

Depression is an illness that affects both the mind and the body. It is not a character flaw nor a spiritual shortcoming. It is a disease. The fact that it is a disease that can be effectively treated by psychotherapy doesn’t mean that it is “made up” or imagined. Modern approaches to psychotherapy, such as cognitive-behavior therapy (the gold standard for treating depression) might be best understood as physical therapy for the brain. Functional imaging technology (fPET and fMRI) has shown that psychotherapy can improve neurological functioning in the regions of the brain that affect emotional processing and stress management in as little as 12 weeks. The exercises a CBT therapist can teach a client, along with medication, actually create observable changes in the brain that enable people to rebound from stressful events and prevent the emotional “flooding” that accompanies depression.

Everyone feels sad from time to time. Normal, transient feelings of sadness or grief are not depression. Depression is a persistent, and sometimes debilitating, feeling of sadness or loss of interest or pleasure lasting at least two weeks that undermines a person’s ability to be their best in their life, work, school or relationships. In addition to the emotional struggles that accompany depression, people can also experience symptoms like fatigue, concentration problems, digestive problems, sleep problems and other physical symptoms. Catching depression early is key to a speedy recovery. Generally speaking, if you find yourself thinking, “I wonder if I’m depressed,” or asking yourself, “How do you know when it’s really depression?” you should talk to your doctor about your concerns.

Depression and faith

People of faith often struggle with what to make of depression. Do faithful people get depressed? Does religion play a helpful or hurtful role in the struggle against depression?

Because depression is an actual disease that impacts the brain’s ability to process emotions and manage stress, it affects people of faith to a similar degree that any other disease can. The good news is that, in most cases, studies show that faith plays a tremendously helpful, positive role in both staving off depression and recovering from it.

A 2011 study published in the Journal of Religion and Health looked at the emotional wellbeing of almost 100,000 women. They found that the women who were weekly churchgoers (regardless of denomination) were 56% more optimistic than women who attended church less frequently or not at all. Because of this, they were also significantly less likely to become depressed, and much less inclined to exhibit a cynical or hostile outlook on life than their unchurched counterparts.

Another article published in the journal Depression Research and Treatment looked at almost 500 separate studies exploring the link between faith and depression. Similar to the above study, the meta-analysis conducted by the researchers found that people who identify as spiritual or religious are 60% less likely to become depressed than the general population. The same study found that when spiritual or religious people do get depressed, they are less likely to become as severely depressed, much more likely to have a positive response to treatment and tend to recover more quickly than those who do not have an active faith life.

Five paths of healing through faith

But why does faith help fight depression, and how can people of faith who are depressed make more effective use of the spiritual resources available to them? Of course, as Christians, we know that God’s grace facilitates healing and wholeness. Unfortunately, social scientists can’t directly observe how grace accomplishes this. Even so, there are many natural benefits conveyed by a healthy religious faith.

Research has found a strong social benefit to religious practices. Psychologist Ken Pargament is an expert on religion and coping, having authored more than 200 studies and two groundbreaking books on the subject. In his book “The Psychology of Religion and Coping: Theory, Research, Practice,” Pargament identifies five pathways that allow people to connect with the healing power of faith.

The first of these has to do with supportive relationships. People who attend church weekly often report having stronger support networks than people who don’t. Regular churchgoers are presented with additional opportunities to connect with others, to check in with each other and to offer support early when problems appear. Also, religious people are regularly encouraged to serve others. Research shows that looking for ways to make a difference in the lives of others can improve our mood and make us feel more effective in addressing our own problems.

The second way faith aids in coping is by helping people find meaning in the suffering. As psychoanalyst Victor Frankl discovered in his personal experience and studies of people who survived the concentration camps, the human person appears to be capable of withstanding almost any degree of even unimaginable suffering if they are able to draw meaning from it. Religion helps people see suffering as an opportunity for personal growth even when a person’s problems are not easily solved. This capacity for meaning-making facilitates hope. If I can hold on to the bigger picture even in suffering, I can believe there’s a reason to work toward a brighter tomorrow.

A third way faith facilitates emotional healing is by encouraging regular religious practices. Research by psychologist Barbara Fiese shows that rituals have a powerful stabilizing influence. Depression often attacks a person’s ability to maintain a normal rhythm of life. Religious faith strongly encourages active participation spiritual habits and character-building activities — participation in the sacraments, church activities, charitable service, personal prayer and study. It also strongly discourages dropping these habits in times of trial. People of faith have strong external motivation to keep up their stabilizing rituals and routines, even when they might personally prefer to give up.

Fourth, religion helps people discover, hold on to and replicate sacred moments. Every person, regardless of their degree of personal faith, experiences “aha” moments; times where we feel caught up in beauty, inspired by excellence or transformed by spontaneous feelings of peace and rightness. Where nonbelievers may enjoy these moments as one-off experiences, religious faith challenges people to explore the deeper meaning and significance of these moments. In addition to facilitating meaning-making, this ability to “conserve the sacred” (as Pargament puts it) facilitates gratitude, which is a powerful antidote to depression. Research by psychologists Robert Emmons and Michael McCullough shows that simple exercises like keeping a gratitude journal or even thanking people for the little things they do throughout the day significantly increases a person’s “happiness set-point” — that is, the normal level of happiness that people experience and/or tend to return to within a few months of experiencing either a major blessing or major crisis. Religion enhances gratitude by reminding people to praise and thank God for both big and small blessings.

Finally, Pargament argues that religious faith promotes coping by helping people connect the dots of their life’s story. This ability enables them to more readily recall how they responded to past crises through God’s help. Instead of treating each crisis as an independent event, people-of-faith are more likely to reflect on what God might be trying to teach them through good and bad experiences. This helps them to potentially approach new problems with a toolbox full of important lessons, insights and resources they have picked up along the way.

When faith is part of the problem

There are times, however, when faith can be part of the problem. The most common issues have to do with extrinsic faith and insecure God attachment.

Extrinsic faith refers to a person engaging in faith practices not because of any personal meaning they draw from it, but from a sense of obligation, duty or the hope that they will be able to achieve some secondary benefit — for example: family approval, social connections of financial gain. Extrinsic faith is exhausting. It makes people feel like they are constantly jumping through hoops or aiming at a constantly moving target. People whose faith is extrinsic often end up thinking of religion as just one more reason to feel like they are failing at life.

“God attachment” has to do with a person’s perception of God. When a person has secure God-attachment, they experience God as a loving, merciful, forgiving presence. God may want the best from us, but he also makes it safe to make mistakes. He is patient with our failings, and he gives us the grace we need to grow closer to him over time.

By contrast, a person with insecure God-attachment may tend to experience God as an angry judge who is always ready to reject them for not crossing every “t” or dotting every “i.” Some types of insecure God-attachments can even cause the believer to relate to God as a trickster who is always changing the rules and willing them to fail.

The type of God-attachment we experience is largely rooted in the way we were parented. The degree to which our parents responded to our emotional needs promptly, generously and consistently tends to predict secure God-attachment, while the degree to which our parents were hesitant, halting or halfhearted about meeting our emotional needs tends to predict insecure God-attachment. People with insecure God-attachment are more likely to experience religion as a contributor to depression because it offers additional confirmation of the belief that the universe has set them up to fail.

How to heal

Research asserts that for mild to moderate forms of depression, psychotherapy alone is the preferred and most effective course of treatment. For more persistent moderate or severe depression, a combined approach of psychotherapy and medication is usually best.

It’s important to note that psychotherapy and medication treat different symptoms of depression. Medication tends to treat the bodily experience of depression — the feelings of lethargy and fatigue, the aches and pains, the brain-fog and other physical sensations of feeling physically “off.” These feelings are more closely associated with the part of the lower brain known as the limbic system. The limbic system helps facilitate communication betwen the brain and the body and is the seat of basic drives (hunger, anger, sex), as well as the fight, flight or freeze response.

According to the National Institutes of Health, medication appears to be less effective at addressing the way depression affects the higher brain, known as the cortex. The cortex is our “rational brain.” It’s responsible for helping us make sense out of our experiences, gathering resources to solve problems, making plans to set and meet goals, and helping us rebound from stressful emotional experiences.

Again, for mild to moderate depression, which tends to produce symptoms related to higher brain functioning, research supports psychotherapy alone as the first line treatment. For persistent moderate and more severe depression, which tends to affect both the higher and lower brain and can affect the whole body, studies recommend both psychotherapy and medication.

To understand how medication and psychotherapy work together it can be useful to compare this relationship to the one between pain medications and physical therapy for treating a physical injury. Pain medication can make it easier to do the exercises that facilitate healing, but the medication itself doesn’t do anything to actually strengthen the muscles or heal the bones. That’s, largely, physical therapy’s job.

In a similar way, antidepressants can ease the physical symptoms of depression that make it hard to develop healthy habits, but it can’t teach you how to manage stress more effectively or process emotions more efficiently. That’s psychotherapy’s job.

In fairness, unlike pain medications, antidepressants are not addictive. They do have some side-effects that need to be considered, but no one should be afraid of taking antidepressants if they are suffering from any level of depression as long as they are prescribed by your physician (and not just “borrowed” from a relative’s medicine cabinet). Even so, mental health professionals largely agree that the effectiveness of antidepressants alone for treating depression has been oversold. The best treatment always involves psychotherapy with medication playing an important, but supportive, role.

Getting the right help

There are many different kinds of mental health professionals. How can you find the right professional to help you in your fight against depression?

Psychologists, clinical social workers, mental health counselors and marriage and family therapists are all state-licensed mental health professionals. Although there are some differences in their educational backgrounds, all of these mental health professionals draw from a similar body of techniques. All of them are qualified to treat depression and other common emotional disorders.

People of faith might prefer to work with a pastoral counselor. A pastoral counselor is a therapist who is licensed in one of the above disciplines, but has additional, post-graduate training in how to ethically and effectively integrate faith and spirituality into clinical practice. The Association for Clinical Pastoral Education is the national accrediting body for pastoral counselors. They also have a nation referral network. Several studies show that clients work best with therapists who can support their values. Pastoral counselors can help clients draw strength from both psychological and spiritual resources.

That said, none of these mental health providers prescribe medication. In most cases when medication is indicated, your general practitioner is more than capable of helping you. In fact, according to the National Association Of Mental Illness, about 20% of visits to a general practitioner are related to depression. If your situation is more complicated, your physician can make a referral to a psychiatrist. These days, most psychiatrists neither do therapy nor are they trained in it. Their practice focuses exclusively on using medication to address more serious and chronic mental illness.

The Lord is close to the brokenhearted

Life can sometimes give us challenges that are hard to bear on our own. The most important thing any person can remember when they are struggling with depression is that there are good treatments, and that God loves them, is walking with them and wants to deliver them. As the psalmist says, “The Lord is close to the brokenhearted, saves those whose spirit is crushed” (Ps 34:19).

Dr. Greg Popcak is the author of many books and the director of CatholicCounselors.com, a national, pastoral tele-counseling practice.

| Scripture to Pray Amid Depression |

|---|

|