VATICAN CITY (CNS) — Although his film is called “Francesco,” director Evgeny Afineevsky said the main character of his new documentary “is us, humanity,” and Pope Francis simply is the one “trying to point us in the right direction.”

Describing himself as “a Jewish boy” initially reluctant to do a film about the pope, Afineevsky said he was looking for a subject that would give him “hope and light” after he finished “Cries from Syria,” a 2017 documentary about the war.

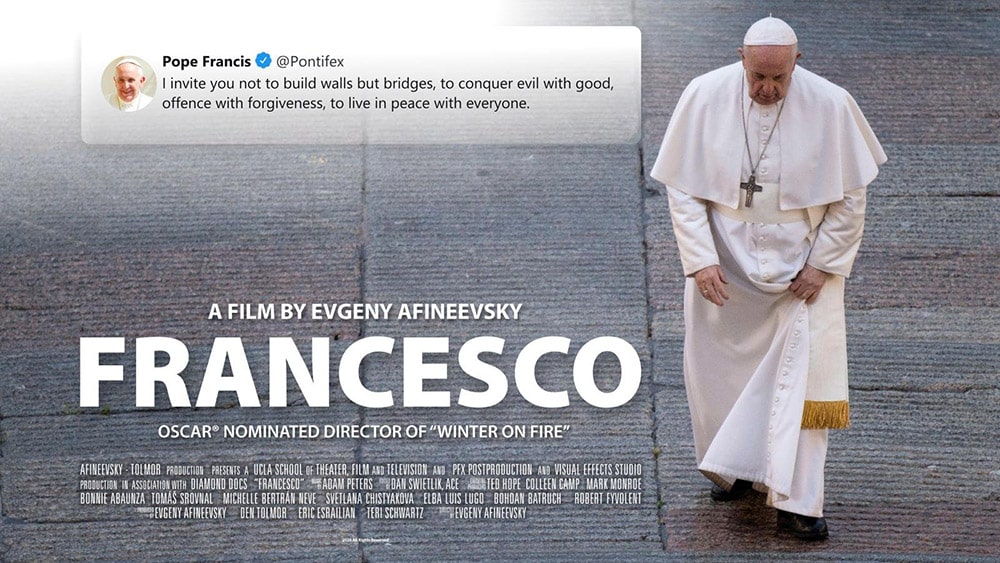

“Francesco,” featuring Pope Francis, debuted at the virtual Rome Film Festival Oct. 21.

Because of the COVID-19 pandemic, Afineevsky said it is not the film he started making in 2018, but the global crisis underscored the director’s main message and provided stark and startling images to drive his point home.

The “zombie towns” created by severe pandemic lockdowns, environmental degradation, immigration and the clerical sexual abuse crisis recur throughout the film.

“It is a story of humanity, which is failing these days,” Afineevsky told Catholic News Service before the film’s debut.

And he sees Pope Francis as someone, “who, through the lessons of his life, has learned a lot from his mistakes and is trying to point us in the right direction.”

Without setting out to do so, Afineevsky has made an allegory to illustrate the main points of Pope Francis’ new encyclical, “Fratelli Tutti, on Fraternity and Social Friendship.”

Many of the crises discussed in the encyclical are grappled with in the film, but even more striking is the film’s illustration of the power of seeing each person as a brother or sister and listening to, learning from, respecting that person and extending a helping hand.

The director said he sees Pope Francis “as an amazing, humble human being who is a perfect role model for older and for younger people” at a time when “we have lost a moral compass.”

Being a perfect role model does not mean being perfect, however.

The film is punctuated by the story of how the clerical sexual abuse crisis in Chile unfolded. Afineevsky includes clips from the pope’s 2018 trip to the country, his cool reception there and his remarks to reporters that survivors reporting abuse had lied.

Through interviews with Juan Carlos Cruz, one of those survivors, and with Archbishop Charles Scicluna, the abuse investigator at the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, the film shows how Pope Francis began to understand he was wrong and took steps to become informed, apologize and take action.

“We’ve seen a leader who knows how to learn and that’s a beautiful thing,” the director said.

The #MeToo movement showed that the same kind of learning needs to take place in the entertainment industry and in society at large, Afineevsky said.

A willingness to listen, recognize another’s pain and take steps to help also are virtues Afineevsky said he hopes to promote in relation to other pressing crises: the need to protect the environment, welcome and integrate refugees, safeguard human rights and end wars — all themes present in the words and actions of the pope and in the film.

The director interviewed more than 50 people for the film not so much to have them explain who Pope Francis is, he said, but to have them help illustrate the qualities Pope Francis has that can help the world. He also did two sit-down interviews with Pope Francis, although he used only a few clips from those encounters.

In one of the clips, the pope insists that gay people “are children of God,” who deserve love and the care of the church. As he did in a 2014 interview with the Italian daily Corriere della Sera and in a 2017 book of interviews with Dominique Wolton, a French sociologist, Pope Francis insisted “marriage” can only be between one man and one woman.

But he also said in the interviews and in the film that “civil unions” may be an appropriate way to protect the legal rights of gay people in committed relationships.

The film begins and ends with Pope Francis in St. Peter’s Square — on March 27 when he prayed in the rain for an end to the pandemic and March 13, 2013, when he greeted the crowd standing in the rain immediately after his election.

“That’s when he began his journey as pope and that’s where we are in the journey right now,” the director said.

“Through this contrast, through these images that are shockingly strong for the viewer, I want to make people understand” that, as Pope Francis often says, the crisis is also an opportunity for people to change the way they are living and interacting with each other.

Afineevsky uses another image from the pandemic lockdown as a sign of hope: people in cities all over the world standing on their balconies or front porches applauding health care and other essential workers.

The applause shows that people still are capable of appreciating the action of strangers, he said, and that even in a divided world, there are good things that bring people together.

Afineevsky described himself as “a nonbeliever fascinated by someone who does not put labels on people” but looks at them and embraces them as a brother or sister.

“He’s saying that together we can make a difference,” the director said. “It is a call to action, and that gives me hope.”