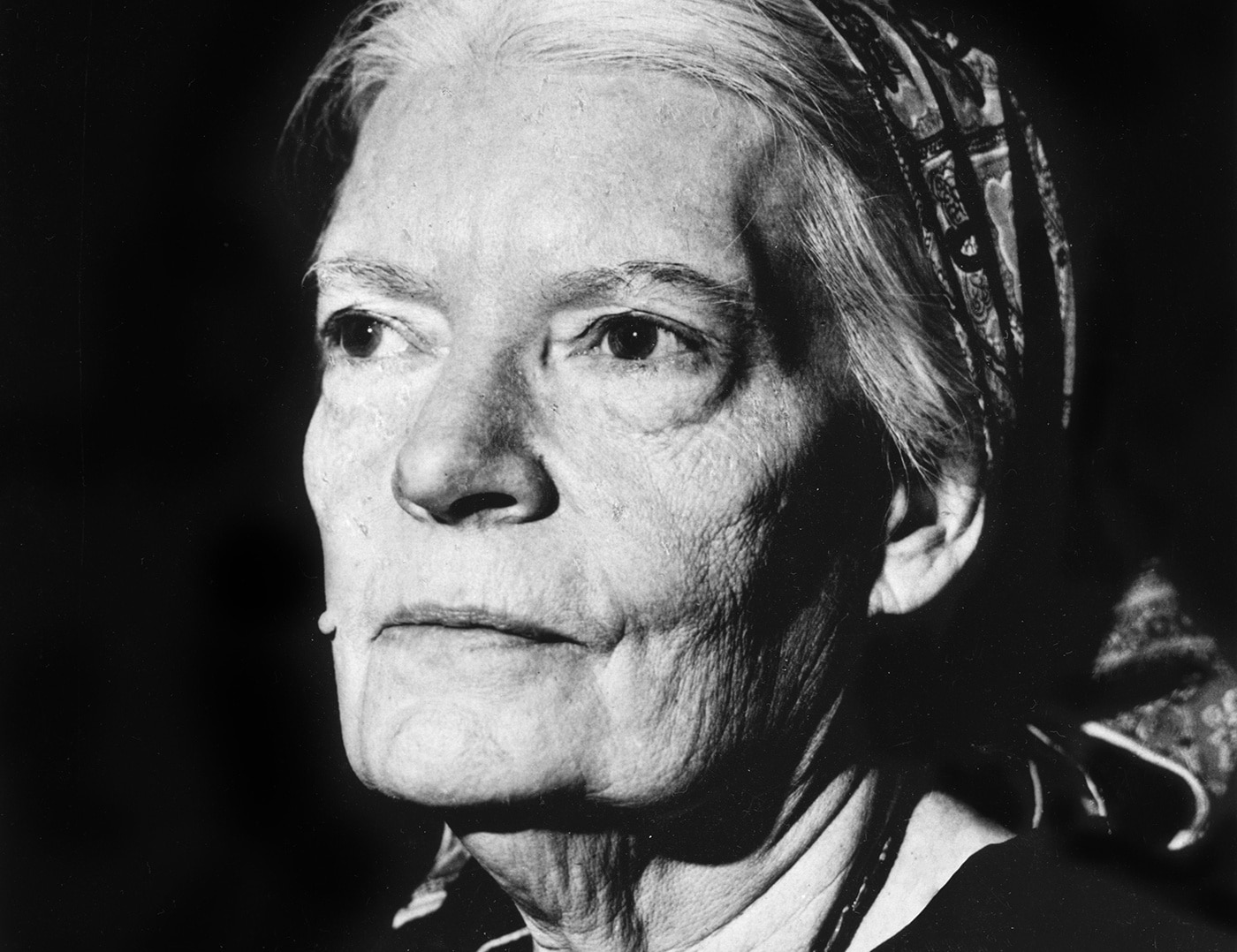

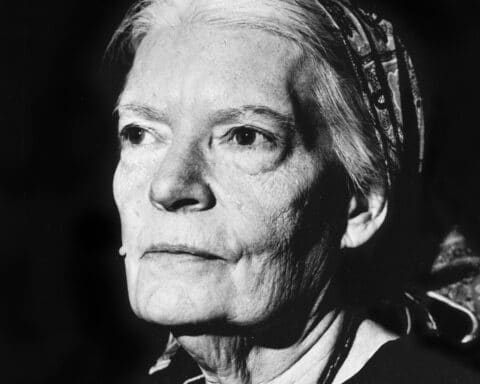

Dorothy Day once said she hoped she’d never be declared a saint, since if she were, people would stop paying attention to what she said. Whether Day gets her wish or not — as this is written, the process that could end with recognition of her sainthood appears to be on track in Rome — interest in this exponent of a radical brand of social justice appears nowhere near diminishing. Lately in fact it reached the point, admittedly short of canonization, of naming a Staten Island ferry in her honor.

Above all, as authors of a recent Day biography say, she was someone who asked hard questions: “Her every statement, her every protest in the street, her lifelong rejection of comfort and respectability, ask: What kind of world do we really want to live in, and what sacrifices are we willing to make to achieve it?”

Early life

Born Nov. 8, 1897, in Brooklyn Heights, she was baptized in an Episcopalian church, but her parents thereafter showed no interest in her religious upbringing. Even so, from an early age, she displayed spontaneous receptivity to things of the spirit. Learning something about praying from a Catholic neighbor, she began inventing her own lengthy prayers while she and her younger sister, Della, played at being saints — “It was a game with us,” she explains in her autobiography “The Long Loneliness” (HarperOne, $16.99).

Her father was a newspaperman whose job took the family to San Francisco and then to Chicago. There, Day, a teenager by now, began to read writers such as Upton Sinclair and Jack London, whose books stimulated her emerging social consciousness. Even at 15, she writes, she felt that “God meant man to be happy … we did not need to have so much destitution and misery as I saw all around.” At the University of Illinois, she joined the Socialist Party, continued her reading in radical literature and scorned church-goers who had no interest in making a better world.

Bohemian lifestyle

Quitting the university after two years, Day moved to New York alone and began her career as a journalist writing for Socialist papers. From the start, her pieces displayed a keen eye for the physical trappings of poverty along with heartfelt empathy with the poor. Sometimes she wrote about pickets and sometimes she joined the picketing herself. In 1917, she took part in a women’s suffrage demonstration outside the White House in Washington, D.C., was arrested along with other demonstrators, and served time in jail, where she read the Bible and was deeply moved by the psalms.

These were the years when Day lived the life of a liberated woman, hobnobbing with journalists, writers, intellectuals and especially with men and women of the left — anarchists, socialists, communists and other radicals. She also pursued a bohemian lifestyle in which sexual promiscuity was taken for granted.

Although Day may eventually be declared a saint, her behavior was anything but saintly. At one point, she had an abortion — a harrowing experience that left her fearful of being unable to bear children. Many years later, writing from the perspective of intense Catholic faith, she said casual sex had “the quality of the demonic, and to descend into this blackness is to have a foretaste of hell.”

Conversion to Catholicism

Having received $2,500 for the movie rights to a novel she’d written, Day used the money to buy a beachfront cottage on Staten Island where she settled into an idyllic life in a common-law marriage with a taciturn anarchist named Forster Batterham. By now, she was praying regularly and sometimes attended Mass. Much to her joy, she became pregnant, and in March 1926, she gave birth to a daughter whom she named Tamar Teresa, in honor of St. Teresa of Ávila.

From the start, she was determined to have her child baptized, but faced with her companion’s opposition, she delayed. One day, walking to the village to buy groceries and saying the Rosary, she met an elderly nun named Sister Aloysia. The two became friends, and Sister Aloysia agreed to arrange the baptism, while at the same time, she repeatedly chided Day: “How can your daughter be brought up a Catholic unless you become one yourself?”

The nun drilled her in the Catechism, and in July 1927, Tamar was baptized. The following December, with Sister Aloysia as godmother, Day was conditionally baptized and made her first confession and Communion. As she had feared, the final break with Forster predictably followed.

She was a Catholic now, but hardly a conventional one. “I loved the Church,” she says in “The Long Loneliness,” yet she judged it to be an ally of “the forces of reaction” that she, a leftist radical, considered abhorrent.

Things came to a head as the Great Depression settled over the land. After covering a communist-organized hunger march on Washington, she knelt in prayer in the crypt church of the Shrine of the Immaculate Conception. The day was Dec. 8, 1932, the feast of the Immaculate Conception. Day writes, “There I offered up a special prayer, a prayer which came with tears and with anguish, that some way would open up for me to use what talents I possessed for my fellow workers, for the poor.”

The Catholic Worker

Then she returned to New York. And there, waiting to meet her at the suggestion of a mutual friend, she found Peter Maurin. Neither knew it then, but this was Day’s turning point — the Catholic Worker had been born.

Maurin was a French Catholic peasant and self-taught theorist with an idea for a reform movement combining radical social restructuring with intense Catholic faith. “He was my master, and I was his disciple,” Day recalls.

Peter Maurin was to die in 1949, but by then, thanks largely to Day’s energy and drive, the Catholic Worker had become a significant presence in American Catholicism, not only helping the poor and outcast but providing a rallying point for other activists and young idealists. It was famous for The Catholic Worker newspaper, which began publication in 1933 and sold for 1 cent per copy, and its houses of hospitality, refuges for the needy and homeless, whose regimen Day described as “living from day to day, taking no thought for the morrow, seeing Christ in all who come to us, trying literally to follow the Gospel.”

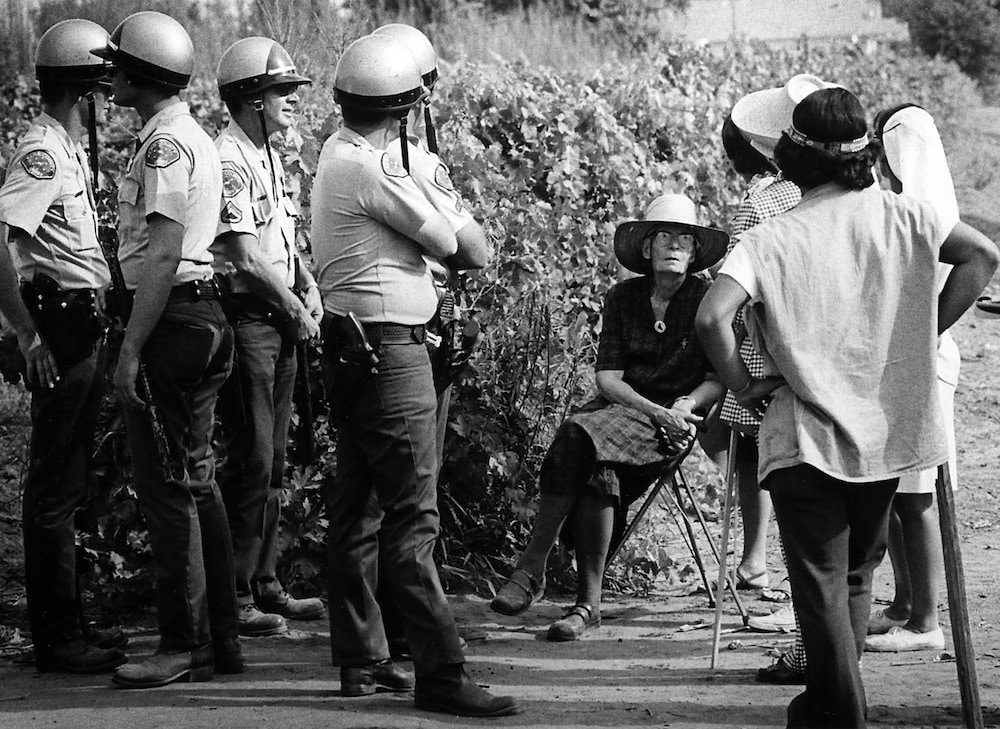

Day did not sacrifice her sometimes unpopular principles for the sake of social acceptability. She refused to repudiate the communists who had been her friends, endorsed pacifism and nonviolence, and opposed U.S. entry into World War II and the dropping of atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. A frequent participant in peace demonstrations, she was arrested several times and in 1956 had the “hellish experience” of 30 days in a women’s house of detention.

At the same time, she remained faithful to the Church and its doctrines. “I believe in the Roman Catholic Church and all that she teaches,” she wrote. “I have accepted her authority with my whole heart. … We are taught that faith is a gift and sometimes I wonder why I have it and some do not. I feel my own unworthiness and can never be grateful enough to God for his gift of faith.”

Day died of a heart attack on Nov. 29, 1980. According to a biography published in 2020, there were then 150 Catholic Worker houses and farms across the United States and another 29 in other countries, while The Catholic Worker had a circulation of 25,000. Day is buried on Staten Island. The headstone on her grave in Cemetery of the Resurrection reads simply, “Dorothy Day, November 8, 1897-November 29, 1980/Deo Gratias.”