“All that was in the past, and the past belongs to God,” the world’s most infamous former seminarian once said to Winston Churchill. “[T]ime is in the Father’s hands; it is in the present that we encounter him, not yesterday or tomorrow, but today,” the Catechism of the Catholic Church declares in the pillar on prayer, tying that encounter explicitly to sharing in the Paschal mystery of Christ.

For once, Joseph Stalin was not wrong, even if he spoke of the past while the Church speaks of the present. For our encounter with God in the Paschal mystery — the Mass, the Divine Liturgy — is an anamnesis, a making present here and now of the chief act of our salvation, carried out in the past by the God made man who was once the child in the manger at Bethlehem.

A cruciform star

The shadow of the cross, the Fathers of the Church said, fell upon the manger where that newborn child lay. Traditionally, the star of Bethlehem, the sign seen in the East that guided the Magi to the King of the Jews that they might worship him, has been represented with four or eight points, with the bottom point longer than the rest, so that it looks less like the five-pointed star that every child learns to draw and more like the cross on which Mary’s son, stripped of his swaddling clothes, would one day die. Even Bing Crosby, 19 centuries later, asks us if we see what he sees: “A star, a star, dancing in the night / with a tail as big as a kite.” The shape of the star tells us just what kind of king this newborn child will be, and how he will save his people.

In a world that still celebrates Christmas but has increasingly forgotten Christ, we remind one another that “Christ is the reason for the season” and urge our fellow man to “Keep Christ in Christmas,” but the way to do so is to keep the Mass, the “-mas,” in Christmas as well. We celebrate our Savior’s birth by gathering together at midnight to commemorate his death. We greet our newborn king by placing ourselves at the foot of his cross and making present here and now the sacrifice through which he redeems every moment of time, past, present and future, washing our sins in his blood and opening for all who believe the gates of heaven.

The great Catholic historian John Lukacs, while acknowledging the paramount theological importance of Easter, used to say that, on both a human and a philosophical level, he preferred Christmas, the feast of the Incarnation, the fulcrum on which all of human history rests. For many years, I agreed with him, in part because of the historical association of Christmas with home and hearth and family; in part because there could be no cross, no tomb, no Resurrection without the Incarnation.

The sacrament of the present moment

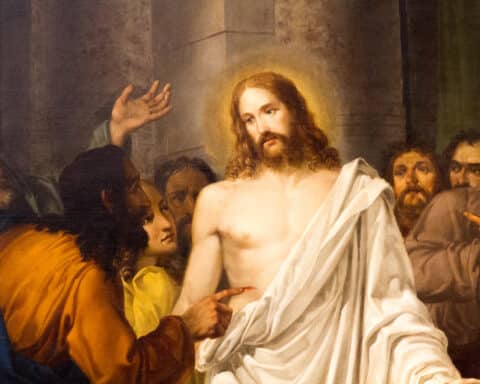

But the older I become, the more I see the shadow of the cross falling on the manger, and the more I recognize that our encounter with Christ here and now is inseparable from the Eucharist, the sacrament not only of Christ’s sacrifice but of his continuing presence in every moment of time. Christmas and Easter are two poles of the same reality. That Christ might have come even if man had not fallen was the subject of interesting and fruitful theological reflections by the Franciscan John Duns Scotus and, before him, many of the Eastern Fathers of the Church. But the reality is that man did fall and Christ did come, and just as his death cannot be separated from his birth, our fall means that his birth cannot be separated from his death.

“[T]ime is in the Father’s hands; it is in the present that we encounter him,” the Catechism says, and we hear in it an echo of the words of T.S. Eliot in the first of his Four Quartets, “Burnt Norton”:

“Time past and time future / What might have been and what has been / Point to one end, which is always present.”

Man fell, and man is falling; our redemption occurred, and is occurring; Christ came, and Christ is coming. All of human history, including the birth of Christ in Bethlehem, led to and is summed up in his sacrifice on the cross, and that sacrifice is made present for us here and now, that we may encounter Christ and rejoice in his birth, and our rebirth.