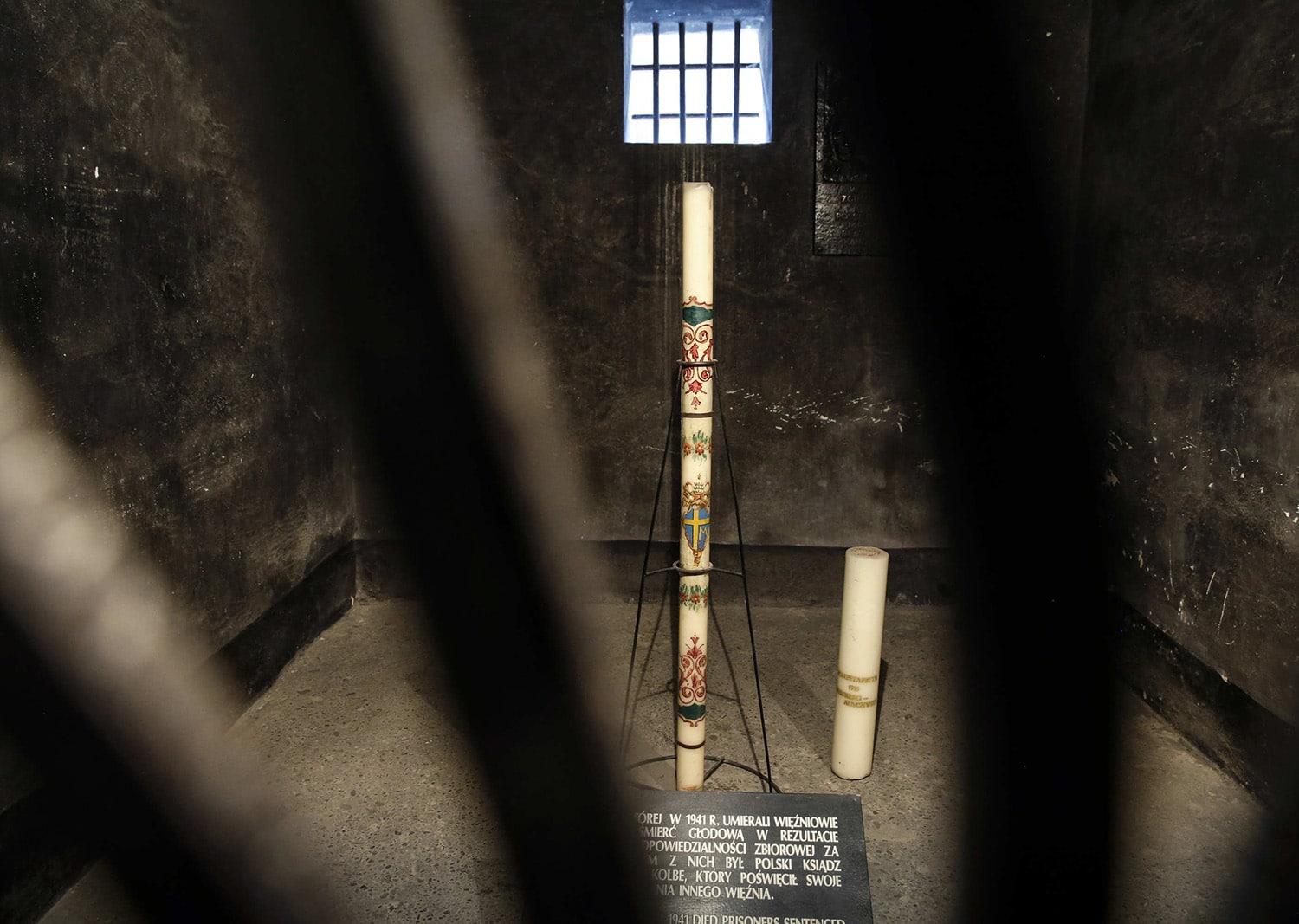

As I stood at the bars of the chilling confines of St. Maximilian Kolbe‘s cell within the walls of Auschwitz, I couldn’t help but be overwhelmed by an inexplicable mix of emotions. The gravity of the place and the memory it held were inescapable. And yet, at the same time, a profound sense of mission awakened in my soul as a newly ordained priest. As I knelt down to pray, the weight of history and the unmistakable presence of God converged in a way that words can scarcely describe.

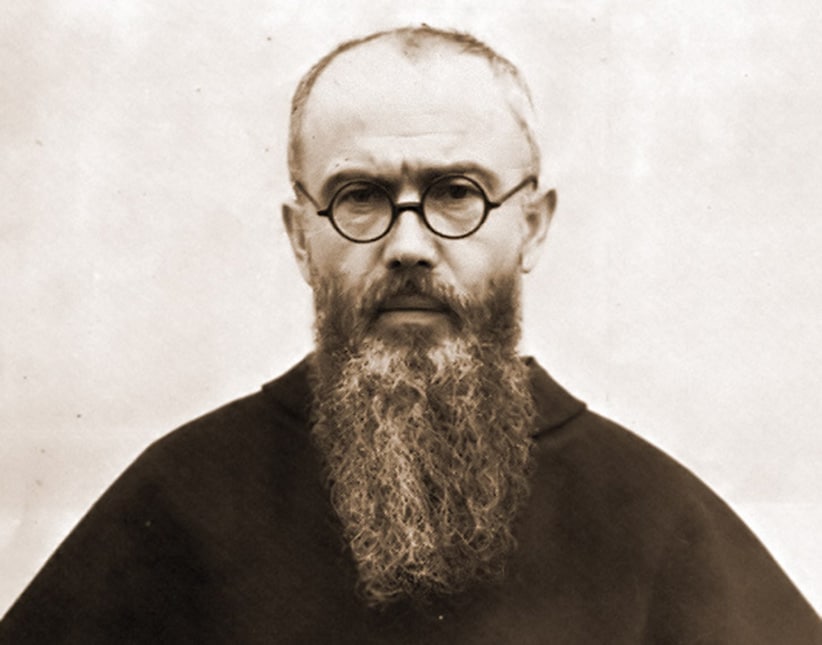

Auschwitz, a name that carries the burden of suffering, genocide and unimaginable cruelty, stands as a stark reminder of the darkest moments in human history. In this sea of despair, St. Maximilian Kolbe’s heroic sacrifice shines like a beacon of light amidst the shadows of evil. A Franciscan friar who offered his life to save another prisoner during World War II, his legacy still combats the horrors of this infamous place.

Praying in St. Maximilian Kolbe’s cell brought forth a powerful realization of the endurance of faith in the face of adversity. His unwavering commitment to the Gospel, even amid the brutalities of Auschwitz, served as a profound inspiration for me, a newly ordained priest just entering into ministry. I wondered: “Would I be able to imitate his courage were I to ever face such evil?”

The light of Christ

In the darkness of Auschwitz, I realized in a profound way that prayer is not merely an individual experience but a connection to the communion of saints. As I prayed in Kolbe’s cell, I felt solidarity with all those who had suffered within those walls. Surrounded by their memory, I was able to sense their current intercession, urging me to remember their stories, to honor their legacy, and to draw strength from their resilience.

When he first joined the Franciscan novitiate, St. Maximilian received his habit and the name by which he is now known. He was also handed a lighted candle. During the ceremony, the provincial who vested him said, “Receive my dear brother, the light of Christ as a token of your immortality, so that dead to the world you may live henceforth for God.” Years prior, at his baptism, a candle had been lit, signifying the light of Christ which had come into his heart. And there, in that cell, he himself had become a light of Christ, with the gifts of faith, hope and charity shining brightly from his heart for all to see.

How fitting then, that Pope St. John Paul II brought a paschal candle to the cell during his visit in 1979. The pope kissed the cell’s concrete floor, and placed the candle, which remains there to this day. That Easter candle — the sign of Christ’s victory — stands in the very place where the Virgin Mary’s beloved servant, St. Maximilian, faced the shadow of death. The words of the Gospel echoed in my ears, “The light shines in the darkness, and the darkness has not overcome it” (Jn 1:5). Pope Benedict too, left a paschal candle in the cell when he visited.

Making the shadows flee

In a letter before his arrest, St. Maximilian wrote, “Faced with suffering and humiliation, human nature is frightened, but in the light of faith, they should be welcomed with gratitude for the purification of our soul!” Confident that the light of faith would transform whatever he faced, the saint’s heart was being prepared for his coming deeds of heroism.

I left Auschwitz having learned an unforgettable lesson. Those walls are an enduring testament that the world is still marred by suffering and cruelty, but it is our sacred duty to combat these evils with love and mercy illuminated by the light of faith.

In the darkest chapters of history, we find the brightest examples of men and women who have been transformed by the light of faith. That light doesn’t explain suffering. It doesn’t demonstrate how human beings could inflict such cruelty on one another.

But it makes the shadows flee. And for me, that is enough.