In his autobiography, Apologia Pro Vita Sua, St. John Henry Newman recalls the great turning point of his life in precise, surprisingly laconic terms:

“I had begun my Essay on the Development of Doctrine in the beginning of 1845, and I was hard at it all through the year till October. As I advanced, my difficulties so cleared away that I ceased to speak of ‘the Roman Catholics,’ and boldly called them Catholics. Before I got to the end, I resolved to be received.”

A few days later, he entered the Catholic Church.

Read more from the Turning Points series here.

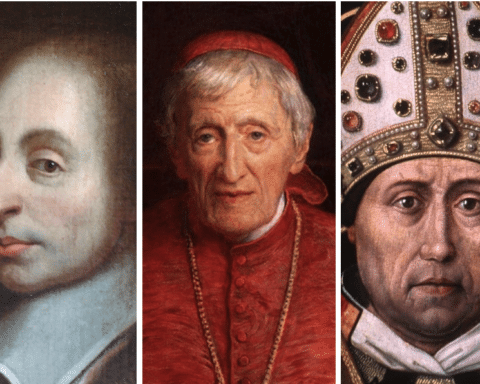

Today, Newman is considered one of the most important Catholic theologians of modern times, a thinker whose ideas strongly influenced the Second Vatican Council. His Apologia has a place of honor alongside St. Augustine’s “Confessions” as an account of a spiritual journey. Yet for all that, his long life was surprisingly marked by conflict and controversy.

A bit of controversy

He was born Feb. 21, 1801, the eldest son in a family of three sons and three daughters, and was raised an Anglican. At 15, he had a conversion experience — the “beginning of divine faith in me” — that moved him to embrace an evangelical form of Christianity with a Calvinist tinge.

He studied at Oxford, in April 1822 was elected a fellow of Oriel College, and in 1825 was ordained an Anglican priest. Several years later, he and several friends began what became known as the Oxford Movement — a loosely organized group of reform-minded Anglicans who sought adoption by the Church of England of teaching and liturgical practices with a Catholic touch. The cause was helped along by a series of pamphlets initiated by Newman and called “Tracts For the Times.”

The Oxford Movement and the tracts flourished from 1833-41. Then came Tract 90. In it, Newman argued that the 16th-century document known as the Thirty-Nine Articles — a key statement of Anglicanism’s fundamental beliefs — was not criticizing doctrines of the Catholic Church as taught by the Council of Trent but only some popular errors of that day. And this, readers quickly realized, was equivalent to saying that the founding document of the church to which Newman belonged implicitly endorsed the teaching of the Catholic Church.

An uproar followed. The Anglican bishop of Oxford ordered that the publication of the tracts be halted. Newman withdrew from controversy and settled into a life of study and prayer at Littlemore near Oxford.

A full conversion

Some say Newman’s Anglican allegiance ended then, but he saw it differently, for he was still wrestling with obstacles to becoming a Catholic. These, he concluded, were largely historical in nature and concerned the fact — if fact it was — that the Catholic Church of the 19th century taught things Jesus and the apostles and Church Fathers hadn’t taught. And if that was so, how could the Catholic Church, as it now was, claim to be in continuity with — indeed, substantially the same as — the Church of apostolic times?

Steeped in the history of early Christianity, Newman now went to work to puzzle that out. The result of his research and reflection was “An Essay on the Development of Christian Doctrine.”

At its start, he states the “assumption” he proposes to test in the book: “that the Christianity of the second, fourth, seventh, twelfth, sixteenth, and intermediate centuries is in its substance the very religion which Christ and His Apostles taught in the first, whatever may be the modifications for good or for evil which lapse of years, or the vicissitudes of human affairs, have impressed upon it.”

That changes had taken place was obvious. But the changes he found to be developments of things already present in the Church’s belief and teaching at the start. Rather than leave this as simply an assertion, he carefully demonstrated how development had occurred in the case of numerous specific instances — papal authority, the Immaculate Conception, the canonical books of the New Testament, the two natures in Christ, infant baptism, purgatory and much else besides.

Newman also made it clear that the idea of development is not a blank check for just any sort of change. Rather, he insisted, certain conditions had to be met: “A development, to be faithful, must retain both the doctrine and the principle with which it started.”

So now at last, his doubts and hesitations had been resolved. In a “postscript” to the introduction of the first edition of the “Development of Doctrine,” speaking of himself in the third person, he notes that the writer had become a Catholic, then adds this:

“It was his intention and wish to have carried his volume through the press before deciding finally on this step. But … he recognized in himself a conviction of the truth of the conclusion to which the discussion leads, so clear as to supersede further deliberation. Shortly afterwards circumstances gave him the opportunity of acting upon it, and he felt that he had no warrant for refusing to do so.”

Productive late career

Newman biographer Ian Ker calls what happened “not just the right time but the providential time to make the final break.” On Oct. 9, 1845, Newman was received into the Catholic Church by Father Dominic Barberi, an Italian Passionist priest who’d lately done the same for a friend of Newman’s. One long journey had ended and another had begun.

Several months after becoming a Catholic, Newman traveled to Rome. There he was ordained a priest and joined St. Philip Neri’s priestly society the Oratorians. Returning to England, he established the Oratory in London and then in Birmingham, where he made his home.

His subsequent career had ups and downs. At the invitation of the Irish bishops, he established a Catholic university in Dublin, but, although the university still exists, Newman’s tenure was not a great success, and he soon returned to England. One offshoot of the episode nevertheless was a set of brilliant lectures collected as a volume called “The Idea of a University.”

During the run-up to the First Vatican Council, Newman was identified with the “inopportunists” who believed the time wasn’t right for a formal definition of the dogma of papal infallibility. But the formulation adopted by the council and approved by Pope Pius IX in 1870 suited him, and he had no reservations about defending the doctrine vigorously.

Newman’s skills as a controversialist also were displayed in his exchanges with Charles Kingsley, an Anglican priest and popular writer, conspicuously hostile to the Catholic Church, who had impugned the truthfulness of Catholic priests in general and Newman in particular.

The result in 1865 was the Apologia Pro Vita Sua (“Account of His Life”), Newman’s “history of his religious opinions” and a masterpiece of self-analysis and religious exposition. Of his conversion to Catholicism, he writes, “It was like coming into port after a rough sea; and my happiness on that score remains to this day without interruption.”

Other important works followed, including the “Essay in Aid of a Grammar of Assent” (1870), a subtle, innovative study of the psychology and epistemology of religious faith, and the “Letter to the Duke of Norfolk” (1875), a spirited defense of the patriotism of British Catholics. He also published novels, poetry, historical studies and several collections of sermons.

In 1879, Pope Leo XIII named Newman a cardinal. Newman chose as his motto a saying attributed to St. Francis de Sales: Cor ad cor loquitur (“Heart Speaks to Heart”). In his latter years, he lived quietly at the Birmingham Oratory while continuing to write and publish. He died there of pneumonia on Aug. 11, 1890, and was declared a saint by Pope Francis in 2019.

Russell Shaw writes from Maryland.