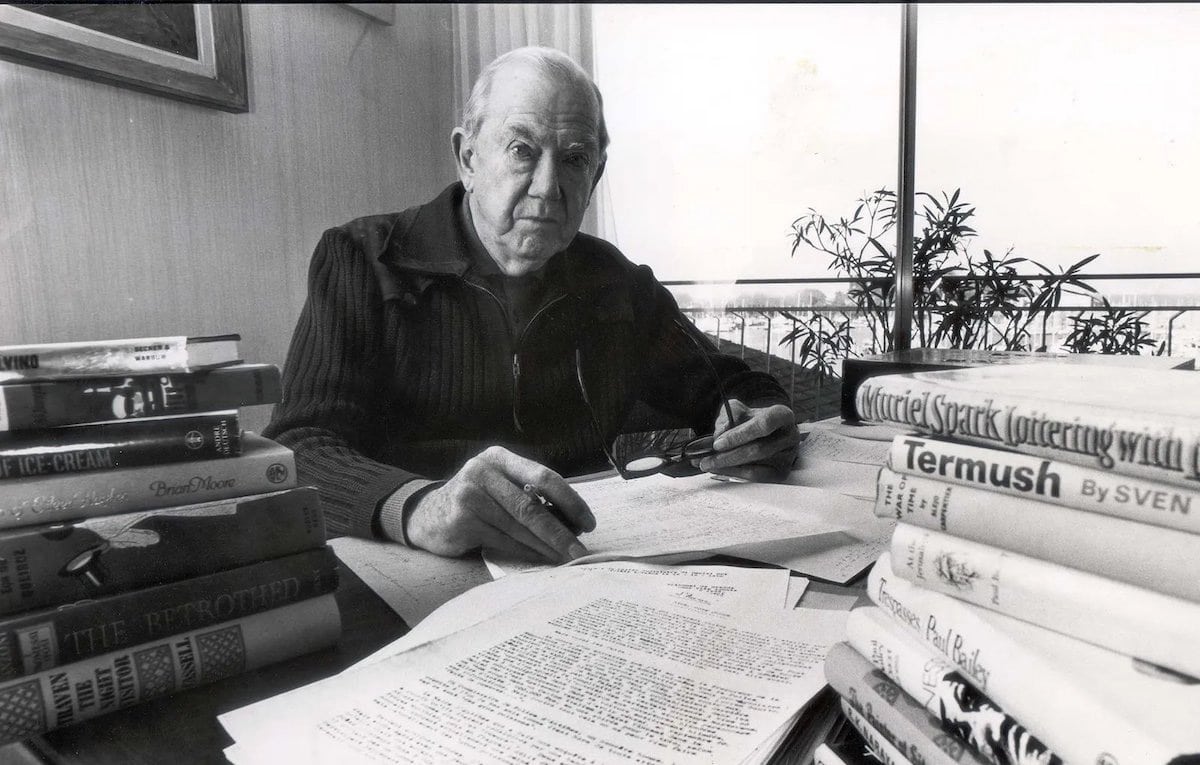

(OSV News) In July of 1948 Evelyn Waugh reviewed Graham Greene’s new novel, “The Heart of the Matter” for “Commonweal” magazine. Waugh used the opportunity not merely to review the book, but to discuss the purpose of the Catholic artist. “There are … Catholics … who think it the function of the Catholic writer to produce only advertising brochures setting out in attractive terms the advantages of Church membership,” Waugh observed.

“To them this profoundly reverent book will seem a scandal,” he continued, “for it not only betrays Catholics as unlikeable human beings but shows them tortured by their faith.” Waugh predicted that “The Heart of the Matter” would “be the object of controversy and perhaps even of condemnation.”

I hope I can be forgiven for saying that Waugh’s review truly gets to the heart of the matter, both with regard to Greene’s book and its argument that good Catholic art may portray Catholics as disagreeable and haunted by their faith.

Waugh’s own greatest novel, “Brideshead Revisited,” can be described in precisely this way. The most (relatively) sympathetic character in “Brideshead” — its protagonist and narrator, Charles Ryder — is an adulterer who abandoned his wife and children before his conversion to Catholicism, and is churlish and rude after. And I know of no character in Catholic literature more tortured by his faith than Sebastian Flyte, the novel’s other central character, who can neither accept nor reject God’s grace.

One might suggest that the Catholic novel is plausible only to the extent that it is filled with unpleasant Catholics who wrestle with their faith. “I do believe, help my unbelief,” pleads the man in Mark 9:24. Greene wove the essence of this prayer into all of his novels, including “The Heart of the Matter.” If that is not the continuing prayer of every Catholic, pleasant or otherwise, we probably do not understand the nature of faith.

Unpleasant characters are not necessarily uninteresting, and Greene’s characters are always acutely drawn and richly developed. Whether the “whiskey priest ” in “The Power and the Glory,” Pinkie in “Brighton Rock,” Bendrix in “The End of the Affair,” or Query in “A Burnt-Out Case,” they demonstrate Greene’s acute insight into the psychological, moral and spiritual nature of the fallen human person. Greene unfailingly places them in a complex web of conflict and tension, probing the depth and richness of Catholic theology and morality that resonates with the scope of the human condition. As Waugh notes, Greene’s “characters are real people whose moral and spiritual predicament is our own because they are part of our personal experience.”

“The Heart of the Matter” may be the best example of Greene’s gift, and possibly his finest novel, thus the anniversary of its publication is an opportune time to revisit its characters and themes. Its protagonist, Henry Scobie, is the deputy police commissioner in a fictional West African port city during World War II. He converted to Catholicism to marry his cradle-Catholic wife, Louise, but his conversion seems sincere and his faith genuine. Indeed, as the novel develops, the authenticity of Scobie’s faith becomes the central device of the novel’s narrative arc. Louise is insufferable; she endlessly complains of climate-illness and constantly nags Scobie to send her to South Africa for a holiday to cure her unnamed ailments. Scobie’s efforts to finance this holiday lead to a series of unfortunate events — among them bribery, blackmail, adultery and murder — culminating in Scobie’s fate.

While the external narrative events are important, Scobie’s moral and spiritual struggles drive the novel. More to the point, Scobie’s sins expose both the depth of Greene’s theological reflection and his skill at probing the shared boundaries of belief and unbelief, salvation and condemnation, heaven and hell. Greene placed a quotation from Charles Péguy in the front matter of the book: “Le pécheur es au coeur même de chrétienté …, Nul n’est aussi compétent que le pécheur en matière de chrétienté. Nul, si ce n’est le saint,” which translates as, “The sinner is at the very heart of Christianity …. No one is as competent as the sinner in matters of Christianity. No one except the saint.”

I do not think, as some of Greene’s critics contend, that Greene included the aphorism to imply that Scobie’s sins were a perverse kind of virtue. Rather, the quote reflects his understanding that the glory of God’s grace is only known in relief to the depths of man’s depravity. Scobie’s transgressions do not bring him closer to God. Rather, they suggest to us that God’s mercy is most acutely known by those who need it most.

As Waugh would concur, this is the heart of Greene’s “profoundly reverent book,” and it’s as true today as in 1948.