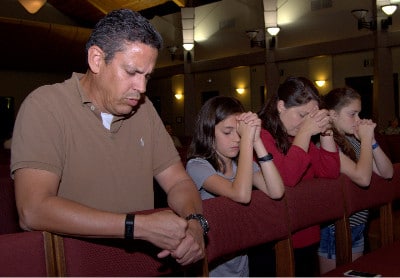

Most families’ attempts to practice the Catholic faith at home are like this. In my many conversations with Catholic families, a consistent theme emerges. Catholic families feel spiritually inferior. We think that holiness is exclusively exemplified by either priests, monks or religious and that family life is holy only to the degree that we can retrofit monastic and clerical practices into family life. We wonder if we could ever be one of those families who can get all their kids to daily Mass and weekly adoration, or do one of those well-meaning but exhausting programs that promote a family “rule of life.” We never feel like we can do enough ministry at the parish or in the community because the need to minister to our spouses and kids keeps “getting in the way.” We think, “Sure, um, we can fit the Liturgy of the Hours in … somewhere.”

People don’t realize that monastic spirituality is a specialized version of the natural family. That’s why religious orders are made up of father abbots, mother superiors and reverend sisters and brothers. In pagan Rome, “family,” with few exceptions, referred to blood relations only. You were either in the tribe or out. One of the things that made Christianity so controversial early on was that it reinvented the family. It claimed that grace was thicker than blood. Through baptism, all Christians became sons and daughters of the Father and brothers and sisters to each other. The religious and monastic movement was an outgrowth of this vision of family. Christian men and women (brothers and sisters in Christ) gathered together in religious communities and celebrated life as little branches of the family of God. They structured their spiritual families around the rituals and routines of the natural family. Their “rule of life” served as a kind of spiritualized version of a chore chart. Community members witnessed to the value of Christian service by caring for each other and their homes. They saw this everyday work as an integral part of their spiritual practices — as any good family should. They developed their charisms and missions — for example, education, hospitality, health care, social work, etc. — which are essentially religious takes on the medieval idea of a family business passed down for generations from father to son.

Families who think we must look more like monasteries to be holy have it entirely backward. The basic framework of monastic holiness is familial. It came from us.

None of this is to say that monastic life is a mere copy of the natural family. It isn’t. And because the dynamics of monastic life are different from the family (e.g., in general, they focus more on their vertical connection to one another rather than the natural family’s more horizontal focus), the monastic movement was able to foster spiritual approaches that were unique to it. Even so, families who think we must look more like monasteries to be holy have it entirely backward. The basic framework of monastic holiness is familial. It came from us.

Unfortunately, too many families completely discount the million-and-one ways natural family life is holy. We write off the countless sacrifices that creating a loving family requires. We think all that work is somehow “selfish” because “it just benefits me.” We say, “It’s not like I’m out there feeding the hungry,” as we wear ourselves to a frazzle trying to lovingly make a meal that our hangry kids will actually eat.

While families can certainly gain tremendous inspiration from our monastic and religious brothers and sisters, when families try too hard to adopt monastic spiritual practices — for example, a more regimented “rule of life,” exclusively contemplative approaches to prayer, emphasizing service to the parish or community over service within the family, etc. — we become like Mark Twain’s ill-fated, ill-translated story. We take an approach to spirituality that has been translated from family life and then retranslate and impose it again on actual family life. The result is clunky at best, suffocating at worst.

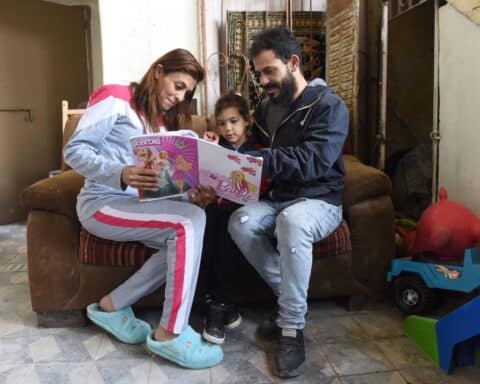

That’s why I believe projects like the Liturgy of Domestic Church Life and the CatholicHOM app that supports it are so important. Families must remember that long before God created monasteries, the Church or even the sacraments — back to the beginning of time — he created family life as the original path to holiness and the primary way he communicated his love to the world. Families deserve to discover and celebrate the paths to holiness that are integral to family life itself.

Dr. Greg Popcak is the executive director of the Peyton Institute for Domestic Church Life and the founder of the CatholicHOM app.