The Resurrection is the most real event in human history. Christ’s bodily resurrection is bedrock reality, both of spirit and of matter. On this rock all other Christian beliefs, visions and practices are built. In reference to it alone do they retain meaning. The Resurrection is no mere metaphor. It is the story at the center of our cosmos; all our hope for this world and the next grows out of it. If we dilute or gloss over the reality of the Resurrection, we miss the core purpose and character of Christian faith. Yet it can be challenging to hold on to a lively and literal sense of an event that can seem so distant in history and so diffuse in its consequences. Literature can be of special help here, not so much to recapitulate the biblical narrative — which has its own unique strength — as to help us understand the inner logic of a world permanently changed by Christ’s resurrection.

The historical Gospel claim

Belief in the Resurrection’s reality requires a level of trust which the postmodern mind, accustomed to poking holes in both sacred and profane narratives, can find it hard to muster. This feels especially true in a moment of great and widespread respect for global religious traditions, many of which contain compelling resurrectionlike myths and tales of their own. How are we to maintain the claim that these traditions, whatever reverence we may lend them, are still to be seen as at most prefigurements and protoevangelia: cultural preparations, expressions of a deep human yearning, given to the world to help us embrace the reality of Christ as an ultimate truth? How are we to hold to the belief that Christ’s story is not just one more myth on the same level as others — no lesser than these, but also no greater — but rather, as novelist J.R.R. Tolkien styles it, “Myth become Fact”?

It may feel tremendously risky to stake so much on the historical verity of one moment in time of which we did not witness and can only document based on the reports of those of his followers, who claimed to have encountered the risen Jesus in the days and weeks between the Resurrection and the Ascension. Even the Catechism of the Catholic Church admits that “No one was an eyewitness to Christ’s Resurrection and no evangelist describes it. No one can say how it came about physically” (No. 647). Of his own purpose, Christ seems to have wanted to leave no evidence “perceptible to the senses” for us to rely upon (unless one considers, for example, the Shroud of Turin as evidence, which many reasonable people do).

So we have to rely on the established facts of the Gospel narratives, which are the vision of the empty tomb, the reports of Christ’s disciples as they saw and touched his hands and side and shared meals and conversations with him, and above all the witness of the martyrs. And of all these we have at least as much documentation as we have for many other demonstrably real events in the ancient world: no more, but also no less.

We have then to contend with the metanarrative fact that the Gospels, unlike many other time-honored world-religious texts, make the claim that their transcendent events really happened in history. The Gospels are not “once-upon-a-time” tales. Nor do they unfold on some unconfirmable though resonant mythic plane, caught halfway between time and eternity. Instead, they happened in the city of Jerusalem and its environs, which were part of the Roman Empire in the time of Caesar Augustus, King Herod and Pontius Pilate — historical places, historical figures, whose hard reality is confirmed by other documents of the time. While historians and archaeologists may debate about precise dates, locations and other such details, that only confirms the point. Historians do not do this about the stories of Baldr, Osiris, Persephone, Inanna or other such dying-and-rising mythological figures. The nature of those stories’ claims does not require historians’ input. The nature of the Gospel claims does.

The Christian narrative

Still, reason needs the help of Revelation here, even to confirm that the embrace of Revelation is a reasonable act. And that very Revelation itself came first to the relatively disenfranchised: the holy women led by Mary Magdalene who journeyed to Christ’s tomb on the first Easter morning to anoint his body and found it missing. I am among those inclined to trust the story all the more on this account. That the women would return to their community with their wild grief turned to wild joy, that their story would turn the community upside down, that some would desire to believe them and verify their words immediately, that others would need time and further evidence — all this responds to the test of common sense.

The emotional and psychological testimony of the first Christians’ experience, as found in the Gospels, simply rings true to a mind trained to recognize credible human stories. We hear of his followers’ grief and sorrow, as well as of their genuine belief that Christ’s dead body should have stayed where they had left it, as dead bodies are not known to move themselves. We hear of their reasonable belief that, if Christ’s body had stayed dead yet had moved, the cause of its moving should be found in some other person or persons’ agency. We hear of their failure to find any such person or persons. We hear of the fear of the Roman guards, who were certain they would be blamed for aiding in some supposed sleight of hand, when they had no evidence to give of any such trick. We can easily credit the notion that the guards were bribed by the chief priests to spread a false story about what happened to them — and that they would have been motivated to lie in order to save face (cf. Mt 28:11-15).

We know that the stone sealing the tomb would have taken more than one strong body to move, and yet we find no one anywhere near the situation who is willing to own up to having moved it, not even to save their own lives or livelihoods. We feel the morning dew and chill in the garden, as well as the evening heat and dust on the road to Emmaus; we get the results of Peter’s footrace with John and of Thomas’s hairpin turns of doubt and confession. We find even the grave-cloths neatly folded on the burial slab — a thoughtful detail in which it is possible to imagine an expression of Mary’s home training, along with more than a bit of the good humor she shared with her son: who else but Our Lord, having just defeated death itself, would bother to take the time to fold a towel?

It is just this combination of concrete, mundane detail and overwhelming, ultimate, humanly inexplicable transcendence that characterizes the entire arc of the Gospel stories and gives them their lasting resonance. As literary scholar Erich Auerbach reminds us in his book “Mimesis,” the Gospels are the first narratives of the ancient world that consider the common person and everyday life to be narrative material worthy of treating with dignity, rather than merely lampooning as comic relief. This dignity is rooted in the conviction that the baptized person, freed by baptism from sin and continuing to choose in accordance with that freedom, will not only one day share in the inner life of the Trinity in heaven — but that this life with the Trinity begins now, in the soul and in its relation to the things of this world. This reality lifts up every detail of our life and charges it with significance.

So it is small wonder that the narrative traditions that flower out of Christian cultures follow this step which the Gospels initiate in the long dance of human art. Understanding that Christian “lives are swept up by Christ into the heart of divine life” (CCC, No. 655), storytellers in the Christic tradition tend to see every detail of the physical world as charged with meaning, both within and beyond itself.

We could spend a long time tracing this development through its monastic, medieval and Renaissance expressions, into the early emergence of the novel and beyond. Such an effort would have to fill many books; I want to focus in here on just three peaks of literary expression of a Resurrection-charged world: John Donne’s poem “Resurrection,” Shakespeare’s late-career play “The Winter’s Tale,” and Wendell Berry’s 20th-century novel “Jayber Crow.”

Though not one of these pieces is confirmably written by a practicing Catholic (I bracket all ongoing disputes about Shakespeare’s lived practice of religion; whatever may be the ultimate import of these disputes, they are of limited relevance to the literary value of his work), all of these works nevertheless express a small-c “catholic” understanding of what the resurrection of the body is and means. As such, all are consonant with a large-C Catholic understanding of the reality of the baptized soul in relation to its life here and hereafter. And all are worthy of our close attention.

John Donne

Working poets, that disputatious bunch, may want to challenge my choice of poem here. For John Donne (d. 1631), Anglican poet-priest and champion of the importance of the body to Christian spiritual life, wrote about Christ’s resurrection and our resurrection in him not once but many times. His most famous such piece is the sonnet “Death, be not proud,” which has been justly adopted in centuries’ worth of anthologies, student texts and devotionals.

In a way, the poets would be right. No one with ears could deny the superior profundity, clarity or musicality of that piece. Yet for our purposes, I prefer this poem, “Resurrection,” for its conceptual focus: not on what we hope to escape from, but on what we hope to escape to.

RESURRECTION

By John Donne

Moist with one drop of thy blood, my dry soul

Shall (though she now be in extreme degree

Too stony hard, and yet too fleshly,) be

Freed by that drop, from being starved, hard, or foul,

And life, by this death abled, shall control

Death, whom thy death slew; nor shall to me

Fear of first or last death, bring misery,

If in thy little book my name thou enroll,

Flesh in that long sleep is not putrefied,

But made that there, of which, and for which 'twas;

Nor can by other means be glorified.

May then sin's sleep, and death's soon from me pass,

That waked from both, I again risen may

Salute the last, and everlasting day.

Donne’s sonnet “Resurrection” opens, not with its more famous brother’s commanding form of address, but with a modest plea from the “dry soul” addressed to Christ: “Moist with one drop of thy blood,” the soul hopes to defeat death by that blood’s power, not by its own. But, made bold by grace, the speaker does not stop at death’s defeat. “If,” by this same power, Christ will “in [his] little book my name enroll,” the speaking soul has reason to believe that it will be reunited with its proper body: “made that there, of which, and for which ’twas / Nor can by other means be glorified.”

Glorification — the future participation of the believer in the embodied, communal life of the perfected Church in heaven — emerges here as a keystone of the poem, as it is of faith. The blood of Christ is a key agent in this process, cleansing and cloaking the “too fleshly” life of the believer in the embodied reality of the Incarnation; as such, this can be read as an implicitly Eucharistic poem, expressing a lively confidence in the perennial power of Christ’s sacrifice to save and transform human nature. This confidence is only enriched by a sacramental belief in the Real Presence, which is not metaphorical or allegorical but literal, in which we understand the body, blood, soul and divinity of Christ to be truly present in the bread and wine at every Mass though undetectable as such to the senses. To be sure, this reading goes beyond the author’s discernible intention. Yet the text will carry the reading, so we are within our rights to suggest it.

William Shakespeare

Poetry, because it is closer to song, always has a greater facility in communicating sacred things openly. Drama and the novel, which take a turn toward naturalistic and easily established forms of what historian Carlos Eire has called “social fact,” must show sacred things as we find them in life — that is, often hidden behind or commingled with the profane. In prose, the resonances of resurrection are more likely to occur on the symbolic than the literal level. Though we are about to see that some texts will challenge this pattern, Shakespeare’s drama “The Winter’s Tale” follows the general direction.

THE WINTER'S TALE

"'Tis time. Descend. Be stone no more. Approach.

Strike all that look upon with marvel. Come,

I'll fill your grave up. Stir, nay, come away.

Bequeath to death your numbness, for from him

Dear life redeems you."

-- Paulina, "The Winter's Tale," Act 5, Scene 3

The core plot of this play is one of misapprehension: King Leontes accuses his wife the queen, Hermione, of being unfaithful to him with their mutual friend Polixenes, a neighboring king. Maddened with jealousy, and interpreting signs of friendly affection as evidence of secret lust, Leontes comes to believe that the child Hermione carries is not his own but was fathered by Polixenes. Just days after the child’s birth, Leontes forces Hermione through a mock trial, in which he sentences the newborn to death by exposure and Hermione to execution.

Just because a resurrection experience has taken place, this does not mean the story is over.

But before the sentence can be carried out, a messenger rushes into the courtroom with news that the royal pair’s first son has died — apparently of shame over the public accusations and sorrow over his consequent separation from his mother. Hermione, her strength already taxed by the recent birth, faints so thoroughly that she too is thought to have died. The twice-grieving Leontes still sends his infant daughter away with a courtier, but she is rescued by a shepherd who does not know her identity.

Years pass. The lost princess, Perdita, as soon as she grows old enough to marry, meets the prince Florizel, who is the son of Polixenes with his own queen. Perdita and Florizel quickly fall in love, but Polixenes opposes his son’s marriage to a girl who is evidently common. So the pair follows advice to plead their case to Leontes, who despite everything still thinks kindly of Florizel.

The last act unwinds quickly: the discovery of Perdita’s identity, rather like the story of the Resurrection itself, happens offstage and is narrated to the audience by witnesses. But greater effects are in store, as the play’s last scene involves a literal revival of the supposedly dead Hermione, who has been living in hiding since her false trial. Leontes begs Hermione’s forgiveness, which she grants. Then Shakespeare whisks his characters offstage faster than in almost any of his other comic resolutions, on the fully valid note that they have much catching up — and, implicitly, much repairing of broken bonds and binding up of emotional wounds — to do. A lesson, not spelled out, feels implicit here: Just because a resurrection experience has taken place, this does not mean the story is over. Grace and nature alike will continue to develop and expand on the theme. Yet much of this work will necessarily be private, interior. This insight brings us naturally to the novelistic tradition, which is concerned above all with the territory of the human heart and its movements.

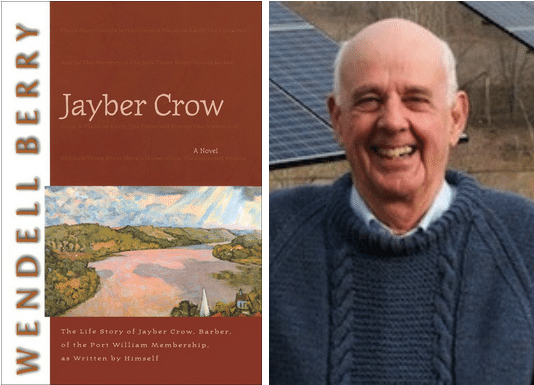

Wendell Berry

Earlier I said we would take a turn back toward more realistic forms of resurrection. This is true, if we remember that not everything realistic is literalistic. Though no one actually rises from the dead in Wendell Berry’s novel “Jayber Crow,” the work nevertheless illustrates in practical terms what it might mean for a soul to, as one of Berry’s best-known poems recommends, “practice resurrection.”

The plot of “Jayber Crow” traces an arc of what is sometimes called “spiritual miracle” — an arc which, though it works outside the Catholic sacramental order, nevertheless demonstrates how grace may build on nature, often without the conscious awareness of the one in whom grace is building. The eponymous Jayber — whose given name was Jonah, but who loses his original identity in the tortuous paths of orphanhood — is a skeptic of institutional Christianity, a man insistent on following his own nature where it leads, and yet, as time goes on, a believer almost despite himself.

Jayber undergoes several symbolic deaths — one when his parents die, another when his adoptive parents do, still another when the orphanage renames him, still another when he first seriously considers a vocation to preaching only to discover that serious doubts about matters of religion block this path for him. After this, Jayber passes through a literal flood — a literary trope for baptism and rebirth, but one deftly deployed by Berry’s light authorial touch — as he returns to his hometown of Port William, Kentucky.

The town remembers Jayber and grants him not only his nickname but also a role, a livelihood and a kind of security. As the town barber, he plays a kind of pseudo-ministerial role, hearing the men’s unofficial confessions, keeping their confidences both overt and inadvertent. Later, he also takes on the role of town gravedigger, which before long makes him responsible for closing the earth not only over heads he had once trimmed, but also — and more poignantly — over those he had once loved.

It is no coincidence, then, that burying the dead — one of the classic works of corporal mercy — becomes key to Jayber’s turn toward reverence. Constant, unavoidable familiarity with the memento mori, along with the practice of mercy, goes to work on him in a manner that is tenderly indifferent to whether Jayber really wants or intends to change — which at first he does not. Without spoiling any events, it’s also fair to say that Jayber eventually takes one of the more peculiar vocational vows in the history of Christian promises around chaste living. Though this vow more consciously motivates him to transform his life for the better, it too works on him in a way that laughs at any thought of “self-improvement” actively sought.

Jayber Crow

"Just as a good man would not coerce the love of his wife, God does not coerce the love of His human creatures, not for Himself or for the world or for one another. ... His love is suffering. It is our freedom and His sorrow. To love the world as much even as I could love it would be suffering also, for I would fail. And yet all the good I know is in this, that a man might so love this world that it would break his heart.

-- Wendell Berry, "Jayber Crow"

And in the grip of this vow, Jayber does not change, but is changed, by what he calls “the way of love.” He comes to see the inner logic of the whole of reality differently: as one in which the mystery of things is tied inextricably with God’s love and Christ’s suffering. More, Jayber begins to find it possible to live this logic, not only to think it. He begins to suspect that the solution to the problem of evil in the world might start with his own life — and not with mere subtraction of the evil in his heart, though that proves its own challenge. But what if, Jayber asks himself, he could demonstrate God’s love for the world by becoming in himself a kind of living proof of that love?

This is the question of a saint, and it receives an answer in kind. What there is of plot in the novel’s final third cannot be done justice by description. It insists on being read on its own terms. And its own terms are a kind of hymnody. Rare among the offerings of contemporary prose fiction (though Marilynne Robinson’s “Gilead” also approaches this territory), Jayber’s song of the goodness of creation is simple without being sparse, pure without loss of realism, and, without a hint of unearned sweetness, deeply moving.

Motifs of resurrection can provide a eucatastrophic turn to stories. That is, they can reverse the downward trend of events, rescue a tailspinning plot, and restore a sense of hope where all seemed lost. A little proper curiosity will turn up these eucatastrophic elements all over our beloved popular narratives. They range from the obvious, like Aslan’s and Gandalf’s returns from the dead in “The Chronicles of Narnia” and “The Lord of the Rings” — or more humorously, Westley’s revival from a “mostly dead” state in “The Princess Bride” — to the subtle, like the “rebirth” experienced by characters in novels like Robert Penn Warren’s “All the King’s Men” or Toni Morrison’s “Song of Solomon.” Again, we should be utterly unsurprised to find resurrection motifs all over the art of a people shaped by the practice of the Sacrament of Baptism. For the logic of that sacrament is the logic of resurrection: in it, Christ’s people participate in his death, not for the sake of dying, but for the sake of rising again.

We tend not to trust the eucatastrophic turn, which is why it can so easily be caricatured, parodied or mythologized out of all recognition, and thereby made to seem remote or unattainable. Nothing could be further from the truth. Participation in the life of grace is open to all who are willing to embrace what it implies. And it is in and through a sacramental imagination that we remember that all things speak of grace, not in a vaguely suffusive or pantheistic manner, but with a clear and recognizable voice whose followers know it when they hear it.