Among the most beautiful of all Catholic practices are the Solemnities of the Most Holy Body and Blood of Christ, the Most Sacred Heart of Jesus and the celebration of Divine Mercy. They are part of the Church’s liturgical calendar because God graced three young women, in different eras, to be his instruments in the development and implementation of these special devotions. Juliana of Cornillon (1192-1258), Margaret Mary Alacoque (1647-90) and Faustina Kowalska (1905-38) were holy women, and though originally unknown to many, were not unknown to God. Each of them claimed to have received visions and messages from Jesus. While the Church does not ask us to believe personal revelations, the results of their visions and impact on the Catholic faith are undeniable.

Through the divinely inspired revelations of these three young nuns, Holy Mother Church offers prayers, practices, and special celebrations that elevate us above worldly things, and calls us to the loving heart of Jesus, to his body and blood, to his Divine Mercy.

St. Juliana of Cornillon | Corpus Christi

Beginning in 1208, Jesus would use a pious, holy and humble nun, St. Juliana of Cornillon, as his instrument to take advantage of the increasing visual adoration of the Blessed Sacrament and, at the same time, return the People of God to regularly receiving holy Communion. Juliana would be Christ’s source to establish the feast of Corpus Christi.

Pope Benedict would say of Juliana, “She is little known, but the Church is deeply indebted to her, not only because of the holiness of her life, but also because, with her great fervor, she contributed to the institution of one of the most important solemn liturgies of the year: Corpus Christi.”

Born in 1192, near Liege, Belgium, Juliana was orphaned at age 5 and placed in the Augustinian monastery at Mount Cornillon, where she spent most of her entire life. Beginning when she was a teenager, and for several years, she experienced a near continuous vision of a bright moon with a dark line across it. Eventually she had a dream where the Lord explained to her that the moon represented the Church year with all its feasts and the line depicted the lack of such a special day that honored the Eucharist. Jesus asked Juliana to establish a feast day during which the faithful would adore the Blessed Sacrament, when they would seek pardon for the times they had distanced themselves from Jesus in the sacrament.

She was uncertain that she could accomplish the task that Jesus commanded and, on several occasions, asked that the cause be given to someone else. Juliana prayed: “Lord release me, and give the task you have assigned to me to great scholars shining with light of knowledge, who would know how to promote such a great affair. For how could I do it? I am not worthy, Lord, to tell the world about something so noble and exalted. I could not understand it, nor could fulfill it” (“The Feast of Corpus Christi,” Barbara R. Walters, Vincent Corrigan and Peter T. Ricketts). But Jesus had made his choice, and he would be with her, guide her and place others along the way to help.

Juliana waited nearly 20 years, when she had been selected as the superior of her convent, to make her visions known. She delivered the secret to her confessor, Canon John of Lausanne, who, in turn, explained the visions to others outside the convent. The reception was mixed, but one who believed Juliana and recognized the value in a feast day to honor the Eucharist was Robert de Thorete, bishop of Liege. He ordered such a feast within the Liege diocese to begin around 1246. Unfortunately, Bishop Thorete died before the feast was implemented, and it was not added to the diocesesan calendar. The idea more or less was shelved; in fact, some argued that Holy Thursday was already the feast of the Eucharist, as that day celebrated the institution of the Eucharist by Jesus. But Holy Thursday is part of the Triduum, a sad period focused on the passion of Christ. It did not celebrate Jesus in the Eucharist.

As God designed, at the time Juliana made known her visions, there was an archdeacon named Jacques Pantaleon in the Diocese of Liege who favored a feast day dedicated to Jesus. Jacques would become Pope Urban IV (r. 1261-64), and in 1264 he issued a decree supporting the feast day and, at the same time, rejecting the argument about Holy Thursday already recognizing the Eucharist. He issued a papal bull adding the feast to the universal Church calendar, but as was the case with Bishop Thorete, Urban died before the feast was instituted. It would be left to Popes Clement V (r. 1305-14) and John XXII (r. 1316-34) to institute the Corpus Christi feast in the universal Church. In most of the world Corpus Christi is celebrated on the Thursday after Trinity Sunday and is a holy day of obligation; in the United States the solemnity is moved to Sunday.

Over the centuries, and stemming from Juliana, we have many rituals and devotions during which we eagerly and publicly honor the Eucharist — for example, through processions such as those on the feast of Corpus Christi, and the exposition of the Blessed Sacrament (Eucharistic adoration) including Forty Hours of adoration. These rituals and special events draw us closer to Jesus. Of course, such activity is capped by receiving Jesus in holy Communion.

St. Margaret Mary | Sacred Heart of Jesus

It was a young nun named Margaret Mary Alacoque of the Visitation order at Paray-le-Monial, France, who would become Jesus’ conduit to spread devotion to the Sacred Heart throughout the Roman Church.

This is an ancient devotion that began when the Roman soldier stuck his spear into the side of our crucified savior and God’s grace, in the form of water and blood, flowed from his side, from his heart. Saints, theologians, writers and individuals have long recognized the Sacred Heart as the source of endless blessings, mercy and love. But for centuries it was mostly a personal devotion.

In the 17th century, Catholicism was under attack from the spread of Protestantism and the heretical beliefs of Jansenism. The Jansenists, who were Catholics, claimed that only a chosen few people would reach heaven and that God was to be feared. They degraded the humanity of Jesus, including his heart, and wanted the Church to return to rigorous penances of the past. Both Protestantism and Jansenism impacted the fervor the faithful had for many Church teachings, including devotion to the Sacred Heart of Jesus. Jesus would confront this falling away through Sister Margaret Mary.

Beginning in 1673 and over a period of more than 18 months, Sister Margaret Mary claimed to have received visions during which our Lord Jesus displayed his Sacred Heart as the symbol of his love for mankind and told Sister Margaret Mary that she was to be his instrument to spread a universal devotion to his divine heart.

In one vision, Jesus appeared with his “divine heart, enthroned, as it were, in flames, was surrounded by a crown of thorns, and the wound it had received was still open, while a cross more brilliant than the sun, surmounted all” (“The Beauties of the Catholic Church,” F.J. Shadler). According to Margaret Mary, Jesus told her that despite loving mankind so much that he gave his life for them, he was being treated with irreverence, coldness and ingratitude. He wanted the world to recognize the love he continually poured out for them symbolized by his Sacred Heart and for mankind to make amends for their ingratitude.

He urged Sister Margaret Margret to begin a personal devotion to his divine heart by receiving holy Communion every first Friday and spending an hour in prayer the night before, both focused on seeking his pardon and making prayerful reparations for mankind’s desertion of his love.

In another vision, Jesus asked her to establish a Church feast day to honor his Sacred Heart, one to be held on the third Friday following Pentecost. On that day, those faithful to Jesus would attend Mass, receive holy Communion, profess their love and offer reparations for the way he had been insulted by mankind. These visions are the basis for the first Friday devotions and the solemnity of the Sacred Heart of Jesus we have today. The love and compassion of Jesus’ heart dispels the heresies of Jansenism.

When Margaret Mary first attempted to explain the visions, many around her were skeptical. It was St. Claude de la Colombiere, her spiritual adviser, who recognized the holiness, fervor and sincerity of Margaret Mary. Even when she was believed, as a cloistered nun there was little she could do to foster her visions outside of her order. Thus it was St. Colombiere, along with St. John Eudes, who would continue promoting a Sacred Heart feast day to the faithful and to the Holy See. Pope Pius XII (r. 1939-58), in his encyclical Haurietis Aquas, wrote: “The most distinguished place among those who have fostered this most excellent type of devotion [Sacred Heart] is held by St. Margaret Mary Alacoque who, under the spiritual direction of Blessed Claude de la Colombiere who assisted her work, was on fire with an unusual zeal to see to it that the real meaning of the devotion which had had such extensive developments to the great edification of the faithful should be established and be distinguished from other forms of Christian piety by the special qualities of love and reparation” (No. 95).

Universal approval eventually came from the Vatican in August 1856 during the reign of Pope Pius IX (r. 1846-78). In 1899, Pope Leo XIII (r. 1878-1903), encouraged by Catholics around the world, consecrated the human race to the Sacred Heart. In our time, the devotion is celebrated every first Friday Mass, and the solemnity is part of the Church liturgical calendar. The devotion is acknowledged through numerous prayers and depicted in thousands of images, including the image of Our Lord holding his flaming compassionate and merciful heart. Many homes are consecrated to the Sacred Heart. During Eucharistic adoration we revere the Sacred Heart in our Benediction prayers: “May the heart of Jesus, in the most Blessed Sacrament, be praised, adored and loved with grateful affection, at every moment in all the tabernacles of the world, even until the end of time.”

Margaret Mary died in 1690 and was canonized in 1920. Some argue that, like in the 17th century, our fervor for the Sacred Heart is again waning today. Turning to the visions and words of Margaret Mary, once again we can rally to this symbol, this source of Christ’s love.

| Promises of Jesus to Margaret Mary for anyone who practices devotion to the Sacred Heart |

|---|

1. I will give them all the graces necessary in their state of life. 1. I will give them all the graces necessary in their state of life.2. I will establish peace in their homes. 3. I will comfort them in all their afflictions. 4. I will be their secure refuge during life and above all in death. 5. I will bestow a large blessing upon all their undertakings. 6. Sinners shall find in My Heart the source and the infinite ocean of mercy. 7. Tepid souls shall become fervent. 8. Fervent souls shall quickly mount to great perfection. 9. I will bless every place where a picture of my heart shall be set up and honored. 10. I will give to priests the gifts of touching the most hardened hearts. 11. Those who shall promote this devotion shall have their names written in my Heart, never to be blotted out. 12. I promise you in the excessive mercy of my Heart that my all-powerful love will grant to all those who communicate on the first Friday in nine consecutive months the grace of final penitence; they shall not die in my disgrace without receiving their sacraments; my divine Heart shall be their refuge in this last moment. Source: “Modern Catholic Dictionary,” Father John A. Hardon

|

St. Faustina | Divine Mercy

Between 1931 and 1938, a young nun named Sister Maria Faustina claimed to have experienced a series of visions, messages and conversations in which our Lord Jesus asked her to establish a devotion to his Divine Mercy.

The messages imparted to Faustina were received during an era of growing unrest throughout Europe: economic disaster, Hitler and the Nazis were taking over Germany, as were Mussolini and the fascists in Italy. The first concentration camps were built, and the German anti-Jewish Nuremberg laws were passed. Control of most European countries was increasingly in the hands of tyrants, which led to the horrors of World War II. All this came on the heels of World War I that had ended less than 25 years earlier. Jesus told Faustina that “mankind will not have peace until it turns with trust to my mercy” (Diary, No. 300).

The diary reflects that to attain the divine mercy of Jesus, mankind needs a trustful relationship with Our Savior. Jesus tells Faustina repeatedly that we can depend on his love, his mercy if only we turn to him, repent of our sins and trust in him: “Sooner would heaven and earth turn into nothingness than would my mercy not embrace a trusting soul” (Diary, No. 1777). He also repeatedly told her that he wanted her to establish a feast of mercy and hold that celebration on the first Sunday after Easter. He said: “My daughter, tell the whole world about my inconceivable mercy. I desire that the feast of mercy be a refuge and shelter for all souls, and especially poor sinners. On that day the very depths of my tender mercy are open. I pour out a whole ocean of graces upon those souls who approach the fount of my mercy. The soul that will go to confession and receive holy Communion shall obtain complete forgiveness of sins and punishment. … My desire that it be solemnly celebrated on the first Sunday after Easter” (Diary, No. 699) The mercy of Christ that we receive is then shared with our neighbor; as he is merciful to us, we are to be merciful to them.

After St. Faustina died in 1938, the original diary was rewritten by members of Faustina’s order and, based on the contents of that version, both the diary and proposed devotion in 1959 were banned by the Vatican. It was 19 years later that a review of the original documents of Sister Faustina led to the lifting of the ban.

On April 30, 2000, Faustina would be the first person canonized in the new millennia. Pope St. John Paul II (r. 1978-2005) not only elevated Sister Faustina Kowalska to the altar of sainthood, but he said during his canonization homily that “from now on throughout the Church [the second Sunday of Easter] will be called Divine Mercy Sunday.” Certain religious groups are advocating for St. Faustina to be named a Doctor of the Church.

When we attend a Divine Mercy celebration on that special Sunday, we are touched by the beautiful prayers that Jesus gave to Faustina: “Eternal Father, I offer You the Body and Blood, Soul and Divinity of Your dearly beloved Son, Our Lord Jesus Christ, in atonement for our sins and those of the whole world.” And then, “For the sake of his sorrowful passion have mercy on us and on the whole world. Holy God, Holy Mighty One, Holy Immortal One, have mercy on us and on the whole world” (Diary, No. 476).

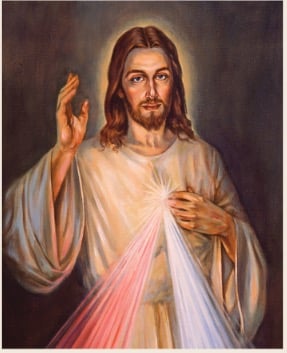

| Divine Mercy Image |

|---|

In many Catholic churches, there is a picture known as the Image of Divine Mercy. According to St. Faustina’s diary, this is how the picture came about: “In the evening, when I was in my cell, I saw the Lord Jesus clothed in a white garment. One hand [was] raised in the gesture of a blessing, the other was touching the garment at the breast. From beneath the garment, two large rays, one red, the other pale. In silence I kept my gaze fixed on the Lord; my soul was struck with awe, but also with great joy. After a while Jesus said to me, ‘Paint an image according to the pattern you see, with the signature: Jesus, I trust in You. I desire that this image be venerated, first in your chapel, and [then] throughout the word'” (Diary, No. 47). |