A central aspect of Lent (and Catholic spirituality more generally) is the surprisingly harsh way that grace sometimes presents itself to us. Of course, it is a staple of Catholic spirituality that suffering can be a medium of grace if it is properly received and ordered. When we join the suffering of Christ, whether in the desert or on the cross, we may discover that grace is communicated through the refinement of our own sense of helplessness. This is a kind of lesson by negation; and it is a hard one. Whether our own or that of a loved one, we discover that we cannot alleviate suffering alone — or, perhaps, at all. Lent teaches us how that sense of futility can be turned to moments of grace if we are attentive to it.

Paradoxical as it might sound, we may even receive grace through suffering the presence of sin and evil. This is not to suggest that we seek sin as a means of receiving grace. As St. Paul put it, “Shall we persist in sin that grace may abound? Of course not!” (Rom 6:1.) For most of us, that’s not an issue; the problem of evil is its abundance, not its scarcity. But the process of conversion — of continuing to order our moral and spiritual lives toward God — is often catalyzed by our exposure to evil.

This is illustrated, for example, in Marilynn Robinson’s novel, “Gilead,” through the book’s narrator, Pastor John Ames. As he becomes frustrated by the persistent and unrepentant sin of another character named Jack, Ames gradually discovers that his exposure to Jack’s sin is ultimately a means of communication of grace to himself. This is grace, he explains, that comes “as sort of an ecstatic fire that takes things down to their essentials.” And it caused in him “a sort of lovely fear,” by which he encountered his own need to be the gracious presence to the very person who caused him so much spiritual and moral frustration. Suffering both the effect and presence of Jack’s sin burnt in the grace by which Pastor Ames could be a redeeming presence to Jack.

Rodriguez’s Company C is led by a captain who maintains a “Most Contact Board,” challenging squads to increase contacts with the enemy. This leads a squad of Charlie Company to plant “contact bait” to facilitate conflicts, which increases casualties on both sides. Because it is frequently difficult to tell civilians from military combatants, these “contacts” often lead to the death of the former. Rodriguez is haunted both by the difficulty of being able to tell which is which and by the realization that civilians have been killed by his squad, perhaps even intentionally.

Rodriguez is not sure what he wants from Father Jeffery, but his soul is deeply disturbed by both the killing and the incipient guilt of contributing to the deliberate killing of noncombatants. And, of course, he is tormented by the catastrophic injuries and deaths of his fellow Marines. To put it simply, Rodriguez is suffering, and he does not know how to deal with it. Even his engagement with Father Jeffery is initially only about borrowing a cigarette, not seeking spiritual guidance. Father Jeffery, sensing something amiss, draws Rodriguez into his confidence.

To Klay’s credit, he does not use Father Jeffery as an easy (and thus implausible) source of resolution to Rodriguez’s suffering. Nor does Klay give us facile answers for the moral ambiguity that is a necessary part of the fog of war. Rather, Klay invites us to enter into the chaplain’s own moral and spiritual struggle in order to reflect on our own Christian witness. As a Marine officer, Father Jeffery tries to report possible violations to his superiors. As a priest, he tries to empathize with — and thus resolve — Rodriguez’s loneliness and guilt. Father Jeffery is frustrated by his own inadequacy in both respects. This struggle is illustrated through two texts within the story: a journal entry by Father Jeffery and a letter from the chaplain’s priest-mentor, Father Connelly.

While he knows of stories of nobility, Father Jeffery notes in his journal, “I see mostly normal men, trying to do good, beaten down by horror, by their inability to quell their own rages, by … their desire to be tougher, and therefore crueler, than their circumstance,” he writes. But yet, “I have this sense that this place is holier than back home … where we’re too lazy to see our own faults,” he continues. “At least here, Rodriguez has the decency to worry about hell.”

In his letter, Father Connelly cautions Father Jeffery not to reach hasty or harsh judgments about the Marines to whom he ministers. Remember that “these suspected transgressions, if real, are but the eruptions of sin. Not sin itself,” counsels Father Connelly. “Never forget that, lest you be inclined to lose pity for human weakness,” he continues. “Sin is … a worm wrapped around the soul, shielding it from love, from joy, from communion with fellow men and with God.” Father Jeffery’s job, the older priest admonishes, is “to find the crack through which some sort of communication can be made, one soul to another.”

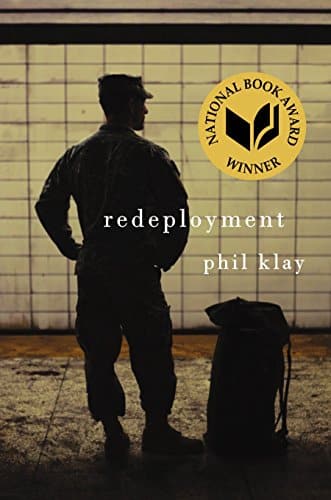

Phil Klay does not give us superficial answers or tidy solutions in “Prayer in the Furnace.” On the contrary, his purpose is to show that the furnace of sin is indiscriminate about whom it burns and fickle about how severely. But he writes with acute Catholic sensibility and deep spiritual insight, challenging his readers to find grace in the fire, and thus to become better Christians, both through our own suffering and through suffering the suffering of others. “In this world,” Father Jeffery reminds us, God “only promises us we don’t suffer alone.” Lent is our own prayer in the furnace, where our suffering can be refined into grace.

Kenneth Craycraft is a columnist for Our Sunday Visitor and an associate professor of moral theology at Mount St. Mary’s Seminary and School of Theology in Cincinnati. Follow him on Twitter @krcraycraft.