Dear Friend,

We are like octopuses. We reach out for what we want. If one way of reaching out is closed to us, we find another way, and another, and another. Strong is our impulse to satisfy our urges. It takes concentrated effort to be free of these impulses. Actually, it takes practice and discipline. These are hard, hard things.

We like to be comfortable. No one likes to be uncomfortable. Our reflexes are bent toward comfort. The key is to retrain our reflexes. Always seeking after comfort makes us less than fully human.

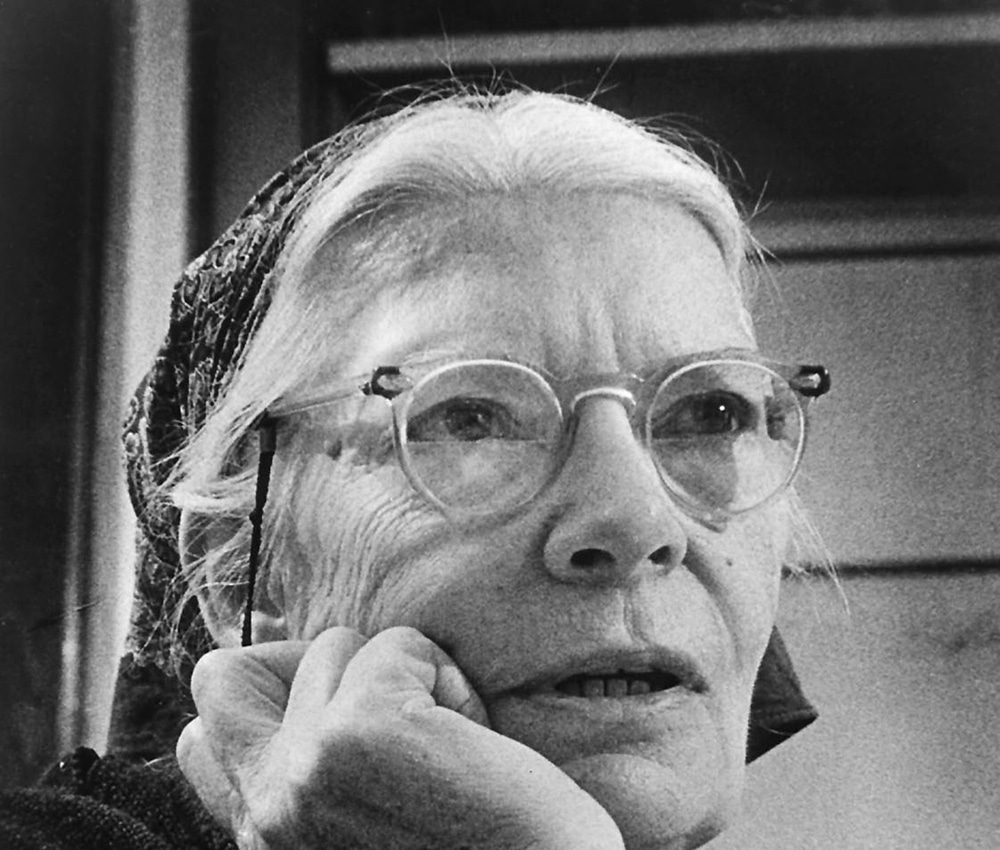

Dorothy Day knew all about this. She slowly learned to desire creating the kind of world where it was easier for other people to be good, to find joy, to be in community. Yet the thing that always got in the way of that desire was the urge to return to a place of comfort. To settle in and protect the little patch of happiness you presently have. To stop seeking what is truly great and beautiful for the sake of what is convenient, close at hand and presently gratifying. Dorothy knew she was like an octopus — we all are.

Here’s how she put it: “You can strip yourself, you can be stripped, but still you will reach out like an octopus to seek your own comfort, your untroubled time, your ease, your refreshment. It may mean books or music — the gratification of the inner senses — or it may mean food and drink, coffee and cigarettes. The one kind of giving up is not easier than the other” (all quotes from “By Little and By Little: The Selected Writings of Dorothy Day”).

Dorothy didn’t have anything against these things. Actually, she liked them. What she knew, though, is that craving any of these things too much, in the wrong way or at the wrong time, would stop her from promptly responding to the needs of others.

She wanted to care about the needs of others — to care about their good — but that desire did not always come easily or without obstruction. Her own impulses got in the way. It is usually easiest to just go back to what you like and prefer and crave. But the line between enjoying these pleasures and becoming a slave to them grows faint if we always let ourselves reach for what we want when we want it.

Read more from the Letters to a Young Catholic series here.

We don’t want what we don’t like. Like many of us, Dorothy did not like uncleanliness or ugliness. Though she desired to seek the good of others, she did not like touching or being near what repulsed her.

Dorothy recalls “kissing a leper” — as she calls it — not once but twice, consciously. The first time occurred when she was giving alms to “a woman with cancer of the face.” The woman tried to kiss Dorothy’s hand. Rather than pulling away, Dorothy went against her own impulses. “The only thing I could do,” she wrote, “was kiss her dirty old face with the gaping hole in it where an eye and nose had been.” This was a direct act of love built upon years and years of trying to tame her impulses and do the hard thing when the hard thing was called for. “One gets used to ugliness so quickly. What we avert our eyes from one day is easily borne the next when we have learned a little more about love.” She learned that love is not all about great feelings; it is about actively willing the good of the other.

The second time she “kissed a leper” was much like the first. About both incidents, she ends up saying that “we suffer these things, and they fade from memory. But daily, hourly, to give up our own possessions and especially to subordinate our own impulses and wishes to others — these are hard, hard things; and I don’t think they ever get any easier.”

Why does this matter for us? Because we are no different than Dorothy. She liked things; we like things. She was called to a greater love; we are called to a greater love. She had to discipline her impulses in order to seek the better part, and so do we.

“You were not made for comfort, you were made for greatness.” Pope Benedict XVI said that, but it might as well have been Dorothy Day, or even Francis of Assisi. Greatness is found in seeking and acting on the good of others. That is where our own good is found. Addictions to comfort get in the way of what is good.

But how are we to be uncomfortable? There are no shortcuts here. The only way is through practicing self-denial and practicing gratitude. Those sound like different things, but in truth they are two sides of the same reality.

Self-denial

No matter what measure of wealth you possess or scarcity you endure in your life, everyone enjoys some comforts. There are probably some super hard-line people who would tell you that Christian life is only about suffering, and so any enjoyment is a sin. That’s nonsense, and those people are delusional. But the truth of the matter is that every comfort, no matter how glamorous or relatively unglamorous, can slowly come to control you if left unchecked. As a Christian, you are called to be free of all attachments and ready to heed the Lord’s call. If you cannot let go of a comfort, then you are not free.

This is why self-denial is so important. We are familiar with this mostly as a Lenten practice: Many people “give up” something they otherwise enjoy. These things that are given up are not, in themselves, bad or harmful, which is why giving them up is a sacrifice. If you gave up defacing property or mocking children, that’s something different. That’s about becoming a decent human being.

But giving up something enjoyable, something that provides some comfort, which you like, is an act of self-denial. The point is not to give these things up forever. Rather, we give them up periodically so as to keep our attachment to these things in check, and to offer our small suffering to the Lord, or for the intention of someone else’s well-being, or both.

Consider St. Francis of Assisi. He may very well be the patron saint of self-denial. He knew himself so well that he distrusted himself around comforts. He knew that he would very quickly get attached to things in the wrong way and he would no longer be free. Once, when he laid his head on a soft pillow, he noticed the comfort, and he immediately sought to free himself from the attachment. So he went outside to sleep with his head on a rock instead. When someone praised him, he would beg one of his brothers to insult him and remind him of his faults. He knew that he would quickly grow attached to praise, so he wanted to counteract it with a heaping dose of humility.

That might all sound crazy to you. It should. It sounds crazy to me. But don’t get distracted and turned off by the intensity and seriousness of Francis’ self-denial. Instead, heed the lesson.

Francis desired the freedom of Christ so much that he would not let other attachments get in the way. We can pursue that kind of freedom by taking small steps. Even outside of Lent, choose one thing each month (or for one week each month) to just give up. Choose something enjoyable, which will make you a little uncomfortable when you give it up. This is the only way we slowly learn to love freedom more than we love all our little and big comforts.

Gratitude

Gratitude can be just as inconvenient and uncomfortable as self-denial. Do you recall those episodes in the Gospels where Jesus heals people and only some of them return to say thank you? It happens, for example, with the 10 lepers he cures. Only one of them returns to give thanks. The others just go on their way, enjoying their new benefits, which are quite grand; they were healed of leprosy, and thus restored to society, so they rush along to enjoy that. But one leper came back and used his new freedom to offer thanks to the one who healed him. That cost him something (cf. Lk 17:11-19).

There is also a woman who had been suffering from a blood disease for decades. This made her ritually impure, and thus she was excluded from social life. She was so desperate that she pushed her way through a crowd of people to lunge after Jesus as a last hope. She barely grazed the fold of his garment with her finger. But when she touched something that was touching him, she was healed. When Jesus turned around, the woman was lost in the crowd. She had gotten what she so desperately wanted, and she likely feared that she had done something improper. Yet, when Jesus calls after the one who touched him, she comes forward. She returns to the one who healed her, and that is the greater wonder. She looks him in the eye and hears him speak to her, personally. That is an exchange of gratitude (cf. Mk 5:25-34)

Gratitude is time consuming, it is often inconvenient, and it costs us something. It is a form of self-denial. You could just enjoy the benefit you received, but instead you choose to suspend your enjoyment to say “thank you” to the one who gave you something. The regular practice of gratitude is a central practice of the Christian life. We become the kind of people we are created and called to be when we offer our gratitude to people who give to us — and, ultimately, to the Lord who gives all.

I close with a hard but undeniable truth: If being Christian does not cost you anything, then you are not really following Christ. The practices of self-denial and gratitude school us in the small and sometimes great costs of following Christ. They help us become fully ourselves, rather than octopuses.

Sincerely,

Leonard J. DeLorenzo, Ph.D., works in the McGrath Institute for Church Life and teaches theology at the University of Notre Dame. Subscribe to his weekly newsletter, “Life, Sweetness, Hope,” at bit.ly/lifesweetnesshope.