They were the ideal couple, the floor model, the textbook example, the paradigm. They had it all. But they didn’t want to be who they were. They wanted to be different people and, in a bold act of the will, transformed themselves into someone else. And then the wheels came off, not only for them but for their descendants, who all repeat the same mistake with the same results.

Adam and Eve were people who loved God and did what he asked, which wasn’t much. Just don’t eat the fruit of that tree over there. They had fulfilling work to do and spent the evenings walking with God in the garden. They had the perfect life.

Then they decided that in addition to being people who loved God, they were people who needed the knowledge he had kept from them. In eating the fruit of the tree of knowledge of good and evil, they alienated themselves from God. No more did they live the perfect life with him in the garden. No more walks in the evening; God sent them away. He would take care of them, in the most astonishing way possible, but they’d have to live the hard life they’d chosen.

They also alienated themselves from each other. Adam, who had been thrilled to have a mate, tries to excuse himself by blaming Eve, as well as God. “You stuck me with her and it’s all her fault,” he said when God asked him if he’d eaten of the tree. (I imagine Eve brought this up later.)

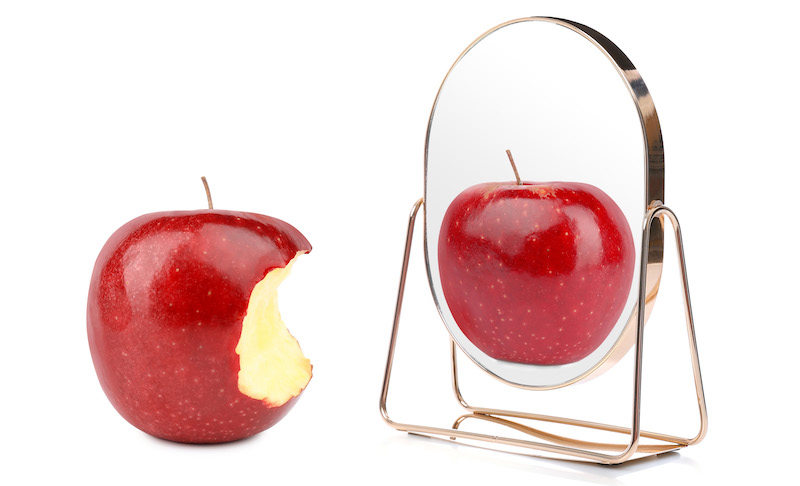

And they alienated themselves from themselves. They lost close contact with the person God made them to be. They could no longer see themselves, see who they really were, as a unique version of the image of God.

And of course the alienation would only grow once the two were out of the garden. Their first born son killed their second in a fit of jealousy. A fratricidal murder just one generation removed from the Garden of Eden, all because Adam and Eve wouldn’t be happy going through life as the persons God made them to be.

And we all do the exact same thing.

Remaking ourselves

The desire to remake ourselves must be something essential to our nature, certainly our fallen nature, since it appears in the Bible’s foundational story, in the lives of two people who had no reason whatsoever to want to be someone else. And yet they did want to be someone else.

It must also be something essential to our nature because we all do it. We see people living by corrupted ideas of who they are all the time and could see it in ourselves if we looked honestly. We don’t want to be exactly the people God made us to be. We prefer a different idea of who we are — life in the garden and something forbidden, too.

Many of the cases are really obvious, and usually sad. The man who thinks he’s God’s gift to women but never notices how women avoid him. The woman who thinks she’s the belle of the ball but doesn’t see the people who roll their eyes when she tries to dominate the room.

The intellectually mediocre young man who thinks he’s smarter than everyone else but complains that others don’t recognize his intelligence or feel jealous. The older man or woman who haughtily and a little judgmentally gives advice on matters on which he or she had noticeably failed. The “life of the party” whose presence will kill a gathering in half an hour.

Other cases don’t appear so clearly, but they’re usually subtler versions of the really obvious ones. We human beings go wrong in a limited number of ways, but some of us go wrong more subtly. We’re better at reading the room and showing people the us we want them to see.

The genuinely intelligent man who sees himself as morally superior to others just because he’s smarter than they are, for example, does more or less the same as the mediocre young man — makes knowledge a measure of worth — but other people respect him and will listen when he speaks. He gets credit while the young man gets pity or annoyance.

Complicating matters is the skill religious people can have of hiding from ourselves the ways we’ve created flattering false images of ourselves. Serious religious practice can mean growing abilities in rationalization and self-delusion.

The desire to remake ourselves must be something essential to our nature, certainly our fallen nature, since it appears in the Bible’s foundational story, in the lives of two people who had no reason whatsoever to want to be someone else.

I can think of examples in my own life, some of which still make my blood run cold with shame or embarrassment. In one case, I’d thought of myself, with not a little pride, as a good friend to a difficult friend, because I was more patient with him than anyone else and people praised me for it. I felt that I was just that kind of person. It was a flattering self-image, and it was wrong.

He erupted one day, and I realized I had not been the good friend I’d thought because though I was patient with him as he spoke, I hadn’t listened well. I hadn’t invested myself in him. He was a friend I cared for, but also — or maybe mainly — a character in the portrait I’d made of myself as David, the good and patient friend who gave his time to people others ignored.

I always thought St. Peter was a simple, good-hearted, impetuous man who loved his friend Jesus and wanted to do more than he could, who shamed himself on Good Friday but stayed with Jesus. A screw up, but a loyal screw up. I’ve loved him for that.

But now I wonder if maybe he had an image of himself as a simple, good-hearted man who’d do anything for his friend — a common one among people I know — whose experience of denying Jesus shattered his self-image in a way that made him even more open to grace and prepared him to become the leader of the apostles.

Faithful living

It seems to me an important subject to think about as we try to live as faithful Catholics in modern America. Today we live in a society possibly unique in history in its power to make us want to be other people. How we live as Catholics requires us to see clearly the world in which we live, the world that wants to make us worldly. That means making us want to be other than the people God made us to be.

A great part of this worldliness is economic. Enormous portions of our economy depend on our endless consumption of new things, which means buying things we don’t need. A vast effort has been made to perfect the sales pitch.

What is the most effective sales pitch to get people to spend more money than they should? How do companies best convince good people to serve mammon? By making us dissatisfied with ourselves, anxious about ourselves, embarrassed by ourselves. By making us, in other words, want to be different people, to feel we must be different because we don’t measure up as we are. And by doing so in ways we don’t notice.

How we live as Catholics requires us to see clearly the world in which we live, the world that wants to make us worldly.

Women’s magazines are a notorious example. The stories are intended to make women feel bad about themselves. She’s too fat. She’s too wrinkled. Her clothing is out of style or unflattering. Her [selected body part] looks bad. Her hair needs straightening, or curling, or dying, or a new, fashionable and also expensive cut. Men won’t like her. The right men won’t notice her. She’s too independent. She’s too dependent. She’s not having it all. She’s missing out on a great sex life. (All cleverly mixed with enough affirmation to keep readers coming back. These people know what they’re doing.)

Basically, whatever the woman does, she’s wrong. And not only wrong, but defective. And — surprise! — there’s a new product to fix every one of her problems.

In the same way, a lot of television commercials intend to make you feel so bad about some part of yourself or your life that you want to change it, and as it happens the product being advertised will change you. Just buy it and your problems go away. So they say.

Toxic ideas

But the magazines and commercials don’t just make people want to be different people, more concerned than we should be with one’s thighs or status. They teach toxic ideas of the ends of human life, about how we should live, so consistently and insistently that most of us accept them to some degree. It’s propaganda preaching a different gospel that’s very hard to resist because it’s not just sophisticated but nearly constant.

The propaganda influences our idea of who we are and makes us want to be different people — more materialistic people. It preaches that the good life requires more and better things. Nearly everything we hear outside church tells us this.

No, it doesn’t make us think the good life requires a huge house and a Lamborghini. That’s obviously wrong. But it does teach us to feel that normal life requires more and bigger things than we would have thought if we only heard the Church’s teaching. It tempts us to relativize all the troubling biblical passages, like “As you’ve done to the least of these” and “it is harder for a camel.” It makes us a different person than we would be without its subtle, pervasive influence.

Who are you?

St. Francis de Sales famously said, “Be who you are, and be that well.” He gave the instruction in a letter to a woman he was counseling in the spiritual life.

“Let us be what we are and be that well, in order to bring honor to the Master Craftsman whose handiwork we are,” he wrote her. “Let us be what God wants us to be, provided we are His, and let us not be what we would like to be, contrary to His intention. Even if we were the most perfect creatures under heaven, what good would that do us if we were not as God’s will would have us be?”

I loved the line when I first read it. The saint affirmed our lives and our selves in a way much of the Christianity I had known had not done. Those traditions had been critical, more interested in examining your moral life and making sure you didn’t violate the rules than in encouraging you to live an active, godly life. Their response to “Be who you are” would have been “That’s the last thing we want you to be.”

“Let us be what we are and be that well, in order to bring honor to the Master Craftsman whose handiwork we are.”

— St. Francis de Sales

But who are we? The handiwork of the Master Craftsman, yes, but what has he made us to be? How do we know who we are when we know ourselves so little and usually believe many things about ourselves that aren’t true? And when we want to be different people than who God created us to be, how do we rid ourselves of the ideas the world preaches so well?

The answer

In other words, how do we know who we are so that we can be that well? As far as I can find, that’s not a question St. Francis de Sales thought to answer directly. He doesn’t seem to have thought the matter as problematic as I do, but then he was a saint and had a better idea of who he was than I do. And he lived in a time when identities were more given, more settled, and the world hadn’t the power of modern advertising.

If he’d been asked, I think he would give his typical instruction: Do faithfully and prayerfully what you’re supposed to do. Grow in holiness through your life. That will teach you a great deal about who you really are.

“The great secret is this: find out what God wants, and when you know, try to do his will gaily or at least bravely.”

— St. Francis de Sales

“The great secret is this: find out what God wants, and when you know, try to do his will gaily or at least bravely,” he wrote to one of the many people he counseled. “Over and above that we must love God’s will and the obligation it lays upon us, even if we have to herd swine all our lives and do the most abject things in the world; for it must be all the same to us.”

In another letter to a spiritual directee, he wrote: “We must love all that God loves, and he loves our vocation. So let us love it too and not waste our energy hankering after a different sort of life, but get on with our own job. No cross is too hard to bear.”

| A Daily Examen |

|---|

|

St. Ignatius Loyola is known for developing the habit and process of making a daily examen — a time to review your day with God, recognizing both the good parts and where you missed the mark. Here’s a brief explanation of the process: Prepare: Begin your time of prayer by calling to mind God’s presence. He has been here throughout your day and desires to be welcomed into its details. Thanksgiving: Speak to God in gratitude for the ways you were blessed that day. Gifts can also be recognized in the ways you grew that day, even if the process was painful or humbling. Review: As the Holy Spirit to help you see your day clearly. What moments stick out? Consider asking yourself: Where did I act as the person God created me to be, or where did I act from a false sense of my identity? Notice the emotions that come to mind when recalling these moments. Respond: Talk to God about these moments. Listen for his voice. What might God be telling you about yourself and his will for you? Follow up with gratitude for the good moments and contrition for where you could have done better. Look to tomorrow: How can your actions and your review from today better prepare you to embrace your true identity in Christ tomorrow? If you know of any stumbling blocks you may encounter, ask God to be with you in a special way during those moments. End in prayer: A simple Our Father or a final prayer of gratitude is enough. |

Do not, he wrote to another, “try to sow other people’s gardens, but cultivate your own diligently. Do not wish that you were not what you are, but rather wish to be perfect as you are. Occupy your thoughts in attaining such perfection, and strive to carry every Cross, be it great or small, that is sent you, patiently.”

No trick but faithfulness

I think learning better who we really are and shedding the different person we’ve become is one of those things we must work on all our lives. St. Augustine said that we are unavailable to ourselves. We’ll never in this life get complete knowledge of who we are, the knowledge Adam and Eve had and threw away. That will come in the next world and be one of the joys of heaven.

There’s no trick to it, except to work at learning to discern what you think about yourself and questioning yourself hard when you’re feeling particularly happy with who you are separate from who you are in Christ.

Life will provide you with times when you will find out how wrong you are, as I had with my friend. You can pray that God will show you who you are through other people being honest with you. You have to be willing to take their words as lessons and not fight them off. It’s hard to hear. They’re telling you that you’re wrong about who you are, and criticism doesn’t get more personal than that.

The main way we learn who we are and how wrong we’ve been about who we are is by living the Catholic life as fully as we can. God teaches us who we are, and he does so in the normal ways he works, through the sacraments, our prayers, Scripture, the disciplines, the teaching, the saints and other wise people, including the Catholic community in which we live.

| Thomas Merton’s Prayer |

|---|

|

My Lord God, Prayer by Thomas Merton, an American Trappist monk |

Each of us in our own way can correct our self-images. The Church is the school for holiness, and holiness clarifies our vision. The examination of conscience and confession, for example, teach us to look closely at ourselves and our real reasons for doing what we do. It humbles us and helps us let go of our false ideas of ourselves.

Maybe if we hear from the Lord, “Well done, good and faithful servant,” his welcome will include the revelation of ourselves to ourselves. It will be a wonderful thing to finally see who we really are.