Some of the darkest days in the 75-year history of Catholic Relief Services (CRS) were in April 1994. Even as there was celebration of Nelson Mandela’s election in South Africa, there was horror at what was taking place in Rwanda: the slaughter of hundreds of thousands of people.

We had been hard at work in Rwanda for decades.

The genocide occurred less than a year after I had been named president of CRS, charged by the Board with putting together a strategic plan informed by a clear vision of our Catholic identity. How did that identity distinguish us? What did it say about our mission?

This eruption of violence in Rwanda had been simmering under the surface for a while, but it was beyond our understanding at the time to appreciate and understand what we could contribute to easing those tensions. We were about building grain silos, supporting maternal and child health programs and feeding children in schools.

And yet, what could we have done about the hatred that was brewing? What should we have done? This post-genocide reflection threw into strong relief the process of examining our Catholic identity.

As you know from reading these columns, CRS was founded as War Relief Services during World War II to assist its many refugees. Our mission was to help people laid low by that war get back on their feet. As the richer nations of the world — prodded by the Church — began to see the moral and practical reasons for helping poorer countries, the work of CRS changed. It wasn’t just to get people back on their feet; it was to aid people who had never been on their feet — economically, at least — in the first place.

This was during the Cold War, when foreign aid was used to win friends and influence countries to join a “side” in an increasingly polarized world. CRS grew as this aid grew, becoming very respected for the competence and professionalism of our development work. Increasingly, we began to look like any other humanitarian organization. There was nothing particularly Catholic about us, nothing that really differentiated us.

Still, we were proud of the work we were doing. We were helping a lot of people and were pleased with our status. But the end of the Cold War changed the aid equation. Then the Rwandan genocide knocked us back on our heels.

During two decades with CRS before becoming president, I had at times been frustrated with our inability to react quickly to dangerous, difficult situations. Sarajevo and Somalia were two in that immediate post-Cold War era. Rwanda put those frustrations into focus. It made our soul-searching go deeper.

We talked with and we listened to our staff — from a driver in Malawi to accountants in India to executives in Baltimore, as well as board members, supporters and other stakeholders. We heard how committed they were to our mission. All wanted to make the world a better place, to help the poor find the lives of dignity that God intends for them. How could CRS as an institution work better to make that happen?

In that process we uncovered the previously unseen foundation that CRS had been built on — Catholic social teaching. The precepts of this century-old strain of Church teaching and doctrine made us realize that we must make our prime goal not building a technocratic development bureaucracy but, rather, building relationships.

Those professional development techniques were useful but just tools, means to get us closer to the end we sought. And what was that end? It was right there in Catholic social teaching.

Concepts like integral human development, subsidiarity and solidarity taught us that if we got the relationships right — with those we were trying to help, with those who were trying to help us and with each other — everything else would fall into place.

Out of this reflection emerged what we termed the “justice lens.” It let us see clearly that our work wasn’t just a matter of providing food or water or seeds or medicine. Rather, it was about serving in a way that fosters good relationships and peace with justice.

Take a water project. We could consult hydrologists and drill a productive well and walk away pleased with ourselves after another success. But look through the justice lens and you see that first we need to talk to community members about what they need and want. We might learn that putting the well in one location would lead to conflicts over access, while another placement could improve communication and ease tensions.

Even as these decisions are made on the local level — subsidiarity — they establish right relationships between and among our staff and those we hope to serve — solidarity.

A piece of the project forms a committee to run and maintain the water system, building an organization that can then help a community deal with regional and national authorities on other issues. The new well means girls go to school instead of spending their days fetching water from a far-off source. The water irrigates crops and nourishes livestock, thus producing more goods to sell. Its purity lessens intestinal diseases.

Empowerment, education, economic gains, health — all from a water project. That’s integral human development in action.

The justice lens led us to incorporate peace building into all our projects — to figure out how drilling a well, distributing seeds, forming a savings group, building a road, stemming erosion, or whatever else we do, can connect people. An important part of that is connecting Catholics in the United States to their brothers and sisters around the world, furthering solidarity.

The justice lens proved to be very effective in Rwanda, where new projects of all sorts brought together the perpetrators and survivors of the genocide, a truly remarkable sight. Out of those dark days of 1994 came a light that CRS has tried to follow to a more just and peaceful world.

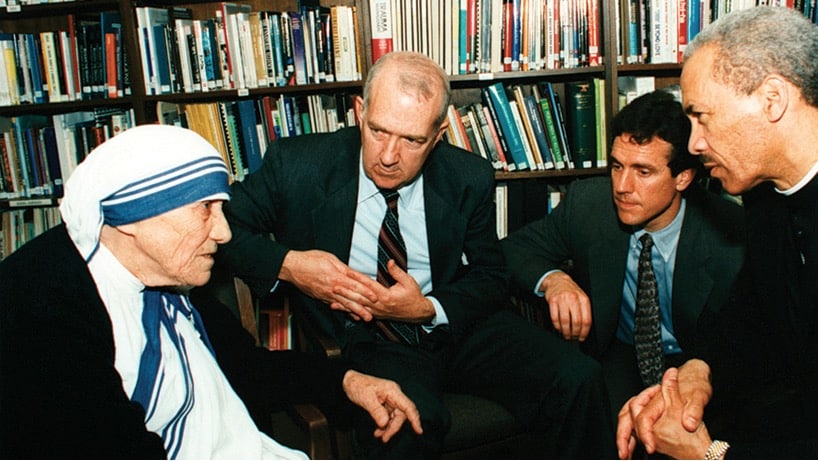

Ken Hackett joined CRS in 1972 and served as its president for 17 years until his retirement in 2012. He was the U.S. ambassador to the Holy See from 2013-17.