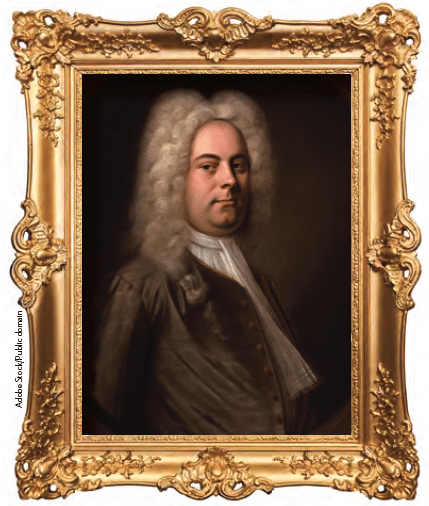

As rector of America’s first cathedral, Father Brendan Fitzgerald can’t wait to host an upcoming performance of perhaps the most famous oratorio ever composed: George Frideric Handel’s “Messiah.”

“My hope is that somehow, someway, to host the ‘Messiah’ at the Baltimore Basilica helps people remember that behind the music and the tradition and the busy activities of the Christmas season is the reality of Christ, whose continued birth into our lives we desperately need,” Father Fitzgerald at the Basilica of the National Shrine of the Assumption, also known as the Baltimore Basilica, said.

He, along with experts in musicology, spoke with Our Sunday Visitor about Handel’s musical masterpiece that draws from scriptural texts ahead of the Baltimore performance on Dec. 16 and the many other performances taking place nationwide around Christmas.

The origin of a masterpiece

Handel, a German-born British Baroque composer, wrote “Messiah” nearly 300 years ago in 1741, in just 24 days. The piece was intended for Easter — not Christmas — and initially sparked controversy. Despite this, performances continued and evolved through the centuries, reaching people across time and religions.

Today, “Messiah” unites Christians in a celebration of Christ’s birth with music that also speaks to nonbelievers. From the beginning, “Messiah” involved several faiths: Handel, a Lutheran, used a text, or libretto, assembled by an Anglican who identified as anti-Deist, to create “Messiah,” which premiered in the Catholic city of Dublin, Ireland.

“‘Messiah’ is truly a universally Christian work of art,” Alexander Blachly, professor of musicology and director of the Notre Dame Chorale and Festival Baroque Orchestra at the University of Notre Dame, in Notre Dame, Indiana, commented. “Today, ‘Messiah’ is sung in concert halls as often as in churches, frequently by performers of every imaginable religion or lack thereof.”

Peter Latona, director of music at the Basilica of the National Shrine of the Immaculate Conception in Washington, D.C., agreed, calling “Messiah” a “wonderful, engaging, dramatic and highly enjoyable musical work which happens to also be a remarkable meditation on the life of Christ.”

“Handel’s ‘Messiah’ is an oratorio (basically an opera without the staging) divided into three parts focusing on the advent and birth of Christ (Part I), His passion and resurrection (Part II), and finally the second coming of Christ and everlasting life (Part III),” he explained, adding that the lyrics come from sacred Scripture as well as from the Anglican Book of Common Prayer.

Listeners are most likely to recognize its famous “Hallelujah” chorus.

“I mean, it’s a really great chorus!” Luke Howard, an associate professor and associate director in the School of Music at Brigham Young University (BYU) in Provo, Utah, and a member of the American Handel Society, said. “But there’s another two and bit hours of music in ‘Messiah’ that are equally as glorious, often in different ways to the ‘woo-hoo’ chest-thumping of ‘Hallelujah.'”

“Messiah’s” longevity, he said, is “truly remarkable.”

“It was composed at a time when most music was quickly forgotten soon after it was performed, and almost certainly never performed again after the composer had died,” he said. “But ‘Messiah’ continued to be performed every year from Handel’s day to the present.”

“No other musical composition from before the 19th century,” he said, “can make a similar claim.”

A Christmas tradition

Handel intended “Messiah” to be performed around Easter, Latona confirmed, even though the oratorio is considered a Christmas tradition today.

“Since oratorio performances served as fund-raising events, some historians point to the fact that the shift occurred because people are more generous during Christmastime and the fact that the duration of the Christmas season provides more opportunities for performance than does Easter,” he said of the change. “Others point to the success of the first American performance in 1818, presented by the Handel and Haydn Society of Boston as the turning point.”

The Boston society takes credit for not only the American premiere of the complete work on Dec. 25, 1818, but also the first national television broadcast of the entire “Messiah” in December 1963.

“I think the reason may also be because ‘Messiah’ and the story it ultimately conveys is one of hope,” Latona added. “The Christmas season is a time when we all (believers and nonbelievers alike) are reminded of the goodness in others and are renewed in our care for and charity toward others; we are reaffirmed in our hope for humanity.”

Composing ‘Messiah’

As director of Handel Hendrix House in London, where Handel wrote and rehearsed “Messiah,” Simon Daniels revealed that Handel began writing the music for “Messiah” in 1741 on Aug. 22 and finished 24 days later on Sept. 14.

“We don’t know what might have inspired Handel to write ‘Messiah,’ but we know that the Italian opera he produced that year, ‘Deidamia,’ had flopped at the box office and it proved to be the last Italian opera he would ever write,” Daniels said. “The taste in London had changed, and from this time onward, Handel devoted his efforts to writing oratorios in English, which were finding more favor with audiences and were more profitable to produce.”

Museum visitors can experience Handel’s writing process through an immersive display in his drawing room, the room where he composed, Daniels said.

“He had a method, writing the melody and bass lines first and then going back to the start to write the inner parts,” Daniels said, adding that Handel recycled some of his existing works and adjusted them to fit the “Messiah” libretto.

Handel would lose himself in his work, he added.

“We also know that Handel worked with great intensity and there are stories of plates of food being left uneaten outside his room,” he said.

Exploring the text

Handel’s Anglican friend, Charles Jennens, compiled the “Messiah” libretto. At Handel Hendrix House, Daniels revealed that, even though Jennens sent Handel the libretto by December 1739, he did not write the music until almost two years later.

“Jennens had previously provided Handel with the libretto for ‘Saul’ and (probably) ‘Israel in Egypt,'” he said of their history. “Jennens hoped that Handel would produce a work that ‘will excell [sic] all his former Compositions as the Subject (“Messiah”) excells [sic] every other Subject.'”

Jennens, however, was disappointed by “Messiah” and reportedly spent years trying to persuade Handel to change the music, according to Latona at the D.C. basilica.

“Given his popularity and the appeal of his music — not to mention his extraordinary musical abilities,” he said of Handel, “I find it interesting that Charles Jennes, a friend and benefactor who compiled the libretto and urged Handel to compose this oratorio, was reportedly not pleased with the way Handel set the text to music.”

“I think working around the familiar Gospel narratives, and combining prophecy with fulfillment through lesser-known verses from both the [Old Testament] and [New Testament] was genius.”

— Luke Howard

At BYU, Howard found the scriptural texts compiled by Jennens “masterful!”

“He may have been a supreme egotist, but he knew his Bible really well,” Howard said, adding at another point, “I think working around the familiar Gospel narratives, and combining prophecy with fulfillment through lesser-known verses from both the [Old Testament] and [New Testament] was genius.”

He described the oratorio as a flashback.

“The opening recitative (‘Comfort ye’) says to cry unto Jerusalem that ‘her warfare is accomplished, that her iniquity is pardoned,'” he said. “It’s already happened; it’s in the past tense. And then the rest of the oratorio is basically, in my mind, ‘and this is how we got there — this is how God triumphs.'”

“So we already know the end of the story at the beginning,” he concluded. “For the faithful, that’s the real comfort — we don’t need to worry whether God wins in the end. He’s already won.”

Examining the music

Experts commented on Handel’s music and its structure, including a technique called word painting, where the melody matches the meaning of the words.

“Handel was a musical rhetorician, as all great Baroque composers were,” Blachly, who directs the Notre Dame Chorale and Festival Baroque Orchestra’s annual performances of “Messiah,” said. “Word-painting was as natural and inevitable to him as breathing.”

With “Messiah,” he said, nearly every musical idea is inspired by the words.

“The opening ‘Sinfony,’ for example, is a French overture, modeled on music devised for the entrance of Louis XIV into the opera hall. He was the king of all worldly kings,” he said. “‘Messiah’ opens with similar music for the King of Kings: highly dotted rhythms expressive of strength and force.”

“The chorus ‘All we like sheep’ has the singers literally evoking sheep running around and getting lost,” he said. “‘The trumpet shall sound’ is written as a great battle fanfare for the Day of Judgment. ‘Why do the nations so furiously rage together’ is written as a typical Baroque ‘rage aria,’ with warlike fast repeating notes for the orchestra in a style invented by [Italian composer] Monteverdi in 1624 that he called the stile concitato, the agitated style.”

For Latona, “Messiah” and all of Handel’s music stands out because of the composer’s “remarkable ability to do so many things with such amazing dexterity.”

He called Handel’s tunes “unbelievably beautiful and memorable” with writing that is “harmonically, contrapuntally and structurally solid.”

“The words are set to music in such a wonderfully communicative way that emphasizes their meaning,” he said. “And finally, his music is dramatic in a way one would expect of an opera; he chooses musical gestures, textures, rhythms and harmonies to cloak the words with great emotional content be it longing, pain, rage, peace or exuberant joy.”

The initial reception

The premiere of “Messiah” in Dublin proved to be a success.

“The advertisements for premiere in Dublin 13 April 1742, at the New Musick Room, Fishamble Street, asked gentlemen to arrive without swords and for the ladies not to wear hooped dresses so that there would be more room to fit people into the theater,” Daniels at Handel Hendrix House said.

At Notre Dame, Blachly spoke about the original size of the performance.

“Although there is a tradition extending back into the 19th century of performing ‘Messiah’ with enormous forces,” he said, “it sounds most like Handel’s other music, and thus most effective, in my opinion, when performed with a chamber choir of 25 to 30 singers and a small orchestra of Baroque instruments, just like Handel’s own forces at the premiere.”

“There’s another two and bit hours of music in ‘Messiah’ that are equally as glorious, often in different ways to the ‘woo-hoo’ chest-thumping of ‘Hallelujah.'”

— Luke Howard

London, unlike Dublin, did not immediately embrace the oratorio.

“Probably the most surprising thing about the history of ‘Messiah’ is that there was great public opposition to the piece when it was first brought to London in 1743,” Blachly said.

“The Puritans objected to having the words of Scripture set in the operatic manner,” he explained. “Even worse, the Theatre Royal in Covent Garden, where the London premiere took place, was a secular venue, and one that was considered a disreputable place, to boot.”

A charitable contribution

On the website for the Tabernacle Choir at Temple Square, associated with the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Howard previously explained that Handel wrote “Messiah” to improve his own fortunes, and yet some of the more successful performances were ones that benefited those in need, particularly at London’s Foundling Hospital, a home for abandoned children. The Dublin premiere also raised enough to free more than 100 people from debtors’ prison.

“The Dublin and Foundling Hospital charitable performances were exceptions, not the rule,” the BYU professor said. “The subsequent tradition of ‘Messiah’ being a work performed primarily for charitable purposes grew out of the Foundling Hospital performances, but didn’t really flourish until quite some time after Handel’s death in 1759.”

Handel, a theatrical composer, turned to oratorio after his opera ventures in London failed in the 1730s, Howard said.

“Oratorio also had the advantage of not requiring a theater for a performance — it could be staged in a church or a music hall, which was cheaper,” he added. “And since it wasn’t overtly ‘theatrical,’ it could be performed during Lent, when the theaters were closed. So writing oratorios in general gave Handel a more stable source of income at a precarious time in his career.”

With “Messiah,” Handel took a risk focusing directly on Jesus Christ, Howard said.

“The words of ‘Messiah’ are all scriptural, which is not the case for most of Handel’s other oratorios,” he said. “So having singers (most of whom were opera singers, and therefore morally suspect!) declaim Holy Writ in a music hall was regarded as sacrilege.”

He suggested that Handel may have premiered “Messiah” in Dublin because he thought he would attract less criticism in that city.

“Making it a charitable performance was a means of winning over some lingering doubters (including, significantly, Jonathan Swift — author of “Gulliver’s Travels” — who was at the time the dean of the main Anglican church in Dublin),” he said. “Handel needed some of the singers from that church choir to help with the premiere performance, so making the performance in aid of charity (so he wouldn’t personally profit from it) was a way of alleviating the concerns around the work at its premiere.”

The following London performances were not charity events, but instead part of the “oratorio season” in Lent, he said.

“By the time ‘Messiah’ was performed at the Foundling Hospital in 1750, Handel’s own financial prospects were in a much healthier state, and he was in a position to be quite generous with his charitable work for the hospital,” Howard said.

Charity was expected of prosperous businessmen at the time, Howard said, and “overt displays of ‘Christian charity’ were important to sustain a man’s reputation.”

At the same time, he said, “I do believe Handel was a true Christian who felt that charitable performances of ‘Messiah’ were most appropriate, considering the subject matter of the oratorio.”

An enduring legacy

Musicology experts shared why they thought the oratorio endured through the centuries.

“There can be only one convincing answer: it is a tremendous crowd-pleaser,” Blachly at Notre Dame said. “Handel, as a composer for the theater, knew how to write music of amazing power but of relative simplicity.”

For this reason, he added, German composer Ludwig van Beethoven revered Handel.

Howard expressed that there is no easy answer to the question of “Messiah’s” enduring popularity.

“I think one possibility is that, for the believer, this isn’t just a story that we’re casually interested in,” he suggested. “We are actual participants in the story.”

“Look at the first-person pronouns in some of the famous choruses: ‘For unto us a child is born,’ ‘Surely, He hath borne our griefs and carried our sorrows,’ ‘All we like sheep have gone astray,’ ‘Worthy is the Lamb that was slain, and has redeemed us,'” he said.

“All that ‘us’ and ‘we’ is actually us and we,” he said. “This is our story.”

At the same time, the music speaks to non-Christians, he stressed.

“You don’t have to ‘believe’ in the doctrine of ‘Messiah’ to appreciate what a grand, cosmic story is being told through magnificent music, just like you don’t need to ‘believe in’ Hercules or Orpheus to be moved by their stories,” he said. “I think the ongoing popularity of ‘Messiah’ in countries that are predominantly non-Christian (e.g., Japan) testify to the work’s musical strengths and its enduring dramatic impact, independent of its sacred content.”

An ecumenical ‘oratorio’

Other experts agreed that the oratorio can inspire all Christians.

“Handel remained a Protestant all his life, and famously resisted invitations to convert to Roman Catholicism whilst living in Rome during his 20s,” Daniels at Handel Hendrix House said. “But ‘Messiah’ speaks powerfully to Christians of all denominations (and people of other faiths or no faith at all).”

They commented on what makes this oratorio, composed by a Lutheran, beloved by Catholics.

“I feel that it is the essence of the message which ‘Messiah’ presents to its listeners,” Edward Polochick, the award-winning conductor leading the Baltimore performance, said. “And I believe that it is not only beloved by Lutherans and Roman Catholics, but by all people who hold dear and sacred the texts from the Bible, both Old and New Testaments.”

“I absolutely believe that a major part of what makes Handel’s ‘Messiah’ so inspiring and awesome is its ability to break through any divisiveness between religious sects by melding the spoken word with the universal language of music.”

— Edward Polochick

Experts also agreed that “Messiah” presents an opportunity for various Christian denominations and for different religions to join together.

“I absolutely believe that a major part of what makes Handel’s ‘Messiah’ so inspiring and awesome is its ability to break through any divisiveness between religious sects by melding the spoken word with the universal language of music,” Polochick said. “And whatever one celebrates in December, whether it be the birth of Christ, Chanukah, Kwanzaa … the beauty and glory of Handel’s ‘Messiah’ is a spiritual message of unity, love, acceptance and peace to which folks from all walks of life can relate.”

At the D.C. basilica, Latona added: “I feel that beauty in music — as in art — has a way of conveying the truth and beauty of God, of the Divine.”

As inspired art, he said, “Messiah” can still connect those who may not be Christian or even religious with its ability to lift spirits and minds beyond the mundane through music.

The Baltimore performance

Ahead of the performance in Baltimore, the basilica’s director of mission advancement, Maria Veres, agreed that “Messiah” speaks to all.

“Handel’s ‘Messiah’ is Christocentric through and through, which makes it an ecumenical celebration and opportunity for Christians of all denominations to unite in their love for Christ,” she said. “In addition, it’s a Baroque masterpiece that all lovers of beauty can appreciate.”

The performance, with tickets available through the basilica’s website, presents the entire “Messiah” conducted by Polochick. Polochick, who serves as music director of Lincoln’s Symphony Orchestra, has multiple ties with Baltimore: he previously served as artistic director of Concert Artists of Baltimore, a chamber orchestra and vocal ensemble that he founded, and on the faculty of the Peabody Conservatory of Music.

| POPE JOHN PAUL II ON MUSIC |

|---|

|

“Even in the changed climate of more recent centuries, when a part of society seems to have become indifferent to faith, religious art has continued on its way. This can be more widely appreciated if we look beyond the figurative arts to the great development of sacred music through this same period, either composed for the liturgy or simply treating religious themes. Apart from the many artists who made sacred music their chief concern — how can we forget Pier Luigi da Palestrina, Orlando di Lasso, Tomás Luis de Victoria? — it is also true that many of the great composers — from Handel to Bach, from Mozart to Schubert, from Beethoven to Berlioz, from Liszt to Verdi — have given us works of the highest inspiration in this field. … “The Church also needs musicians. How many sacred works have been composed through the centuries by people deeply imbued with the sense of the mystery! The faith of countless believers has been nourished by melodies flowing from the hearts of other believers, either introduced into the liturgy or used as an aid to dignified worship. In song, faith is experienced as vibrant joy, love, and confident expectation of the saving intervention of God.” — Pope St. John Paul II, Letter to Artists, Nos. 9, 12 |

He shared that the performance, a version that he developed at the Baltimore Symphony beginning in 1982, is a re-establishment of a more than four-decade Baltimore tradition.

“Messiah” “is one of the few great masterworks I know of which has been performed every year since its premiere,” he said, adding, “I am honored to be able once again to perform and share such a musical treasure.”

For his part, Father Fitzgerald hopes for beauty to transform the city.

“What really excites me is that on December 16, at the very center of a city consumed by poverty and addiction and violence, there will be so much beauty to be found,” he said, pointing to both Handel’s music and the basilica. “And that beauty comes from Christ.”