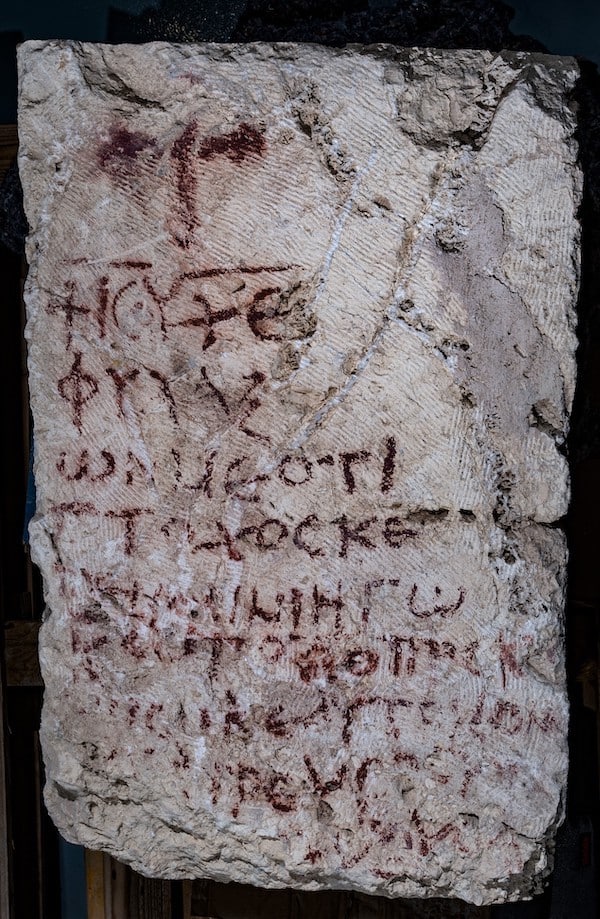

Archeologists with the Hebrew University of Jerusalem recently discovered an ancient Christian inscription paraphrasing Psalm 86 that dates back to the height of the Byzantine era.

The text in Koine Greek — the language of the New Testament — appears painted in red beneath a cross, according to a university press release. The words resemble the start of Psalm 86 and read: “Jesus Christ, guard me, for I am poor and needy.”

The original lines say, instead, “Hear me, Lord, and answer me, for I am poor and needy. Guard my life, for I am faithful to you.”

The archeologists found the text that dates back to the first half of the sixth century on a large building stone at the Hyrcania fortress, located in the Judean Desert between Jerusalem and the Dead Sea.

The inscription likely comes from the remains of a small community of Christian monks who established a monastery there in the fifth century, after the location served as a Hasmonean fortress and, later, a Herodian prison.

An expert weighs in

Gabriel Radle, who serves as the Rev. John A. O’Brien assistant professor of theology at the University of Notre Dame in Indiana, commented on the significance of Psalm 86 in Christianity.

“To find a Greek inscription inspired by a psalm in a church dating to the Byzantine period in Palestine does not surprise me,” he told Our Sunday Visitor. “The psalter was used as one of the most frequent texts of Christian prayer, and various monastic systems existed already in late antiquity for distributing the psalms to specific times of prayer across a set period.”

The words uncovered by the archeologists appear more than once in the Book of Psalms, he said.

“The Greek phrase hoti ptochos kai penes eimi ego (‘for I am poor and needy’) shows up in Psalms 85 (Greek Septuagint numbering; 86 in the Masoretic numbering), as the archeologists note, and could very well be the inspiration here since it features as part of the incipit of that psalm,” Radle said.

“But the expression also shows up in Psalm 108 (109),” he added, “and anyone regularly praying the psalter would have been well familiar with this expression, frequently adopting the words of the psalmist as their own in prayer, and, as in the case of the individual who carried out the inscription, also adapting it in various ways in their own personal supplications to Christ.”

He spoke about the importance of the psalm in the Byzantine era.

“In terms of Psalm 85, in the early Byzantine period it was used as a regular (daily) psalm within the sung cathedral rite of the imperial capital city of Constantinople, where it featured as the first psalm sung at daily Vespers, and there would have been many other churches in the Greek-praying world that would have presumably followed this custom,” he said.

“However, for the region of Jerusalem specifically and its surroundings, at this time, the churches tended to follow a different arrangement of the psalter, and we do not have direct evidence that Psalm 85 was used in as prominent a position there as it was at Constantinople,” he added. “But nevertheless, both Psalm 85 and 108 would have been regularly used alongside all the psalms in any late antique Christian monastic community.”

A rare finding

Epigraphist Avner Ecker of Bar-Ilan University, who helped decipher the inscription, identified the text as a paraphrase of Psalm 86:1-2, according to the press release. After analyzing the text, Ecker revealed that minor grammatical errors in the inscription indicate that the writer, likely a monk, was not a native Greek speaker. Ecker also determined that the inscription occurred within the first half of the sixth century.

The discovery came during a first-of-its-kind excavation earlier this year led by Oren Gutfeld and Michal Haber of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, together with Carson-Newman University in Tennessee and American Veterans Archaeological Recovery.

In addition to the psalm finding, the archeologists discovered another inscription nearby that is currently being studied.

“Few items hold such importance in the historical and archaeological record as do inscriptions — and it must be stressed that these are virtually the first examples from the site to have originated in an orderly, documented context,” Haber said in the press release. “We are familiar with the papyrus fragments that came to light in the early 1950s, but they are all of shaky, unreliable provenance. These recent discoveries are truly exceptional.”