Friends, I think the readings for this Sunday provide the keys to answering this question!

In Leviticus, it says: “You shall love your neighbor as yourself. I am the Lord” (19:18).

Meanwhile, the psalm invites us: “Bless the Lord, O my soul; and all my being, bless his holy name” (Ps 103:1).

And Paul reminds us: “Do you not know that you are the temple of God, and that the Spirit of God dwells in you?” (1 Cor 3:16).

| February 19 – Seventh Sunday in Ordinary Time |

|---|

|

Lv 19:1-2, 17-18 |

Finally, Christ urges us: “So be perfect, just as your heavenly Father is perfect” (Mt 5:48).

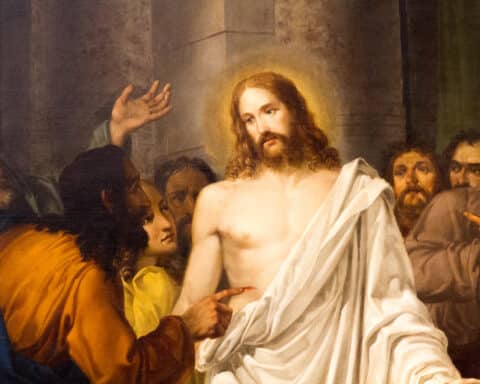

To my mind, these readings come together to provide the contours of being Catholic. Being Catholic most fundamentally means living in relationship with God such that God’s love saturates our very being, entirely and completely. We become, as the readings say, “temples.” This image presents our very lives as a constant, intimate relationship with God. This interior relationship spills out in praise, which includes the love we express for our neighbors.

Perhaps one of the reasons my students pose this question is because they have only encountered Catholicism in the doctrines we profess, and in an incomplete way. Maybe, we all have a need of encountering the radical connection between professing our faith and living it deeply, between faith and the holiness of one so entirely possessed by God’s love to be saturated by it — to be Love’s holy temple.

The theological writings of Pope Benedict XVI are essential here. His first encyclical, Deus Caritas Est, opens by reminding us that Christianity is about an encounter with a person: “Being Christian is not the result of an ethical choice or a lofty idea, but the encounter with an event, a person, which gives life a new horizon and a decisive direction” (No. 1). Desire to understand our faith arises from this encounter and receives its direction. We desire to understand this Person and to let him saturate our lives. This should set our life’s journey in his direction via the shortest route possible: love of our neighbor.

Another teacher of mine, Cyril O’Regan, recently wrote about Pope Benedict XVI in the Church Life Journal: “To the question ‘what is Christianity?’ Benedict provides an answer of startling brevity: Christianity is the seeing of divine love drenching the world that finds its expressive core in the Incarnation, passion, death, and Resurrection of Christ.”

In other words, God expressed his love for us by becoming our neighbor, by opening himself intimately to our friendship. His incarnation, passion, death and resurrection are his entrance into communion with us. Thanks to these events and to this Person, our being is saturated by his — by the one, that is, who is love. Love lived a human life, died a human death, and thereby asked to be our neighbor and friend. He became someone we would love as ourselves.

This is also the core of every doctrine of the Catholic faith. We try to teach this love and to hand it on by giving it expression in our words. Through our doctrine, we try to grab hold of God’s “expressive core” so as to understand him and to be captivated by him and to share him with our neighbor. We try, that is, to live a truly Catholic life: a holy life, for, as O’Regan writes, “holiness is … the fitting response to the gift of love.”

Catherine Cavadini, Ph.D., is the assistant chair of the University of Notre Dame’s Department of Theology and director of its master’s program in theology.