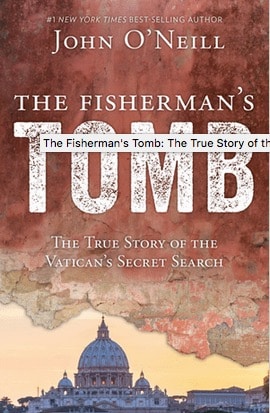

That was the translation of an inscription scratched amid a host of ancient Christian hieroglyphics that pointed at the truth. Tradition long had held that St. Peter the Apostle, martyred in Rome, was buried there. Somewhere under the altar of the basilica named for him. But finding and confirming his bones — his relics — would become a long and controversial search.

O’Neill has spent a good part of his life studying and researching Christian archaeological sites. The experience shows in “The Fisherman’s Tomb.” This book reads — and is written — like a mystery. It involves everyone from a wealthy Catholic Texas oilman to a woman translator of ancient graffiti. It gets caught up in internal Church politics, as well as war and papal deaths.

O’Neill reminds us of the tradition that Peter was martyred in Rome under the Emperor Nero’s persecution of Christians in A.D. 64. He was said to have been crucified head down.

Tradition has it that the Romans tossed his body on a nearby hill — a simple dumping ground — but that Christians returned to secretly bury him there. That dumping ground would later become a Roman necropolis, a Christian burial ground, and eventually the location of St. Peter’s Basilica.

Traditions are traditions, and at times they can be confused with pure fabrication. Tradition had it that the basilica was built over Peter’s burial site, but the Church itself became nervous about the claim. As O’Neill points out, when excavations took place underneath the basilica in the 1620s, the ancient Roman necropolis was discovered.

“Periodic later excavations likewise found pagan graves,” O’Neill writes, “suggesting the horrifying possibility that the great seat of Christianity rested not on the tombs of saints, but on the graves of pagans.” For hundreds of years, digs under St. Peter’s virtually ceased, not to continue again until Pope Pius XI died on the eve of World War II. During his burial under St. Peter’s, in addition to Roman graves, Christian graves were discovered. The new pope, Pius XII, decided to secretly continue the excavations. It is then that George Strake, the Catholic oilman, promised virtually unlimited funding.

O’Neill points out the gamble Pius XII was taking. In a world with secularism and Communism on the rise, if Peter was not found, it would call into question everything from Rome as the home of the Church, to papal authority.

It seemed at first that he succeeded. Pius announced to the world in 1950 that the tomb of Peter had been found and bones discovered were likely those of Peter. But by 1958, forensic studies of the bones make it clear that they could not be Peter. Pius died without the discovery for which he so fervently hoped. O’Neill then introduces the hero of the story. Margherita Guarducci was an expert in “epigraphy,” the forensic study of ancient inscriptions. Brought into the excavations under Pope Paul VI, she found the meaning of the graffiti that had been dismissed as unintelligible. Her faith was reborn translating the early Christian graffiti on the excavated walls.

The rest of O’Neill’s story follows Guarducci. He notes that the inscriptions she translated “highlight the continuity of Christian belief down through the millennia. Peter occupied a central role in the Church and in the hearts of the early believers.” And, as confirmed by Pope Francis in 2013, we know that Peter was found within.

Robert P. Lockwood writes from Indiana.