Chris Lewis believes in preserving tradition, up to a point.

It was the ages-old, rock-solid history of the Catholic Church that first grabbed his attention and made him take his adopted faith seriously. The Georgia-based graphic artist and illustrator at Baritus Catholic Illustration had joined the Church as an adult. He was raised a Bible Christian and drifted into functional atheism; but when he met his wife and her Catholic family, he had to take another look.

“If you love somebody, you’re going to be interested in what they’re interested in,” Lewis said.

So he began asking questions and was astonished to find out that Catholics had answers.

The first thing he wanted to know was who the first pope was. When his mother-in-law told him it was Peter in the Bible, he said it was a “wake-up slap in the face.”

“Within one question, I had a connection to history in Jesus’ time, and that led to all kinds of subsequent questions. So I picked up the Bible and started reading again,” he said.

He also spent time just staring at the massive, soaring, overwhelming architecture and stained-glass windows of the church he and his new wife attended, trying to make sense of what he was seeing.

Teaching with images

He internalized the lesson: You can teach with images.

At the time, Lewis was making his living as a graphic designer. Like so many Americans, he had begun his artistic life as a kid producing copious comic book superheroes and then shifted to crafting pixel art, square by square. These were both decent training for his eventual career in corporate branding, producing polished images and logos to sell products for his clients.

But as his new faith started taking root, it became more insistent, and he began to think, “If this is what I’m staking my belief on, I’m going to take it and put it in my art.”

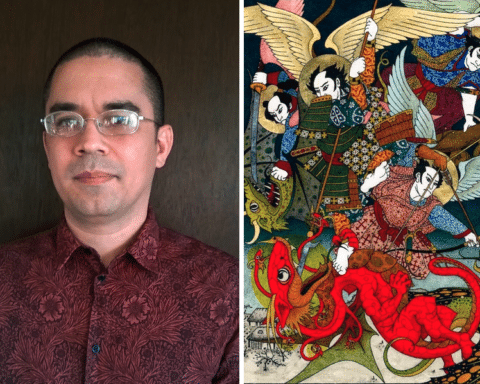

“I kind of took the very formal polished approach of graphic design, but the more storytelling approach of comic books, and the simplicity and limited color palettes of pixel work and made the style that fused all my beginnings,” Lewis said.

The result is a look that’s dynamic and accessible like comic books, but with more heft and dignity; it’s polished like graphic design, but infused with authentic emotion; and yes, it’s designed to fit into a square with only a few colors, so it prints well.

So along with doing design and illustration work for various authors, publishers, archdioceses and more, Lewis also has a thriving retail business for stickers, T-shirts, cards, posters and phone cases. Some of them are iridescent; some of them glow in the dark.

Preserving tradition

How does this popular, accessible work jibe with the history and tradition he found so compelling in his own faith journey?

“When I say I’m trying to preserve tradition, I mean more the substance. But in the form it takes, there’s a bit of flexibility there,” Lewis said.

He never deliberately twists tradition just for the sake of putting his personal stamp on it, but he does allow himself to play with the interpretation of a theme. A good example is his depiction of St. Thérèse of Lisieux.

“I was used to seeing her holding flowers and looking sweet and a little bit saccharine. That vintage stuff resonates with me, but if I tried it, it wouldn’t look authentic. I have a version where she’s dropping rose petals on a demon, and he’s bursting into flame. It’s basically a retelling of her killing with kindness,” he said.

At first, he was nervous about introducing Catholics to grittier vibes.

When he portrayed St. Joseph, terror of demons, he drew on his previous experience designing album covers for heavy metal bands, and he didn’t know how a Catholic audience would receive a saint picture that included writhing satanic figures with glowing eyes.

“I didn’t want to rub the Catholic moms the wrong way. But they’re the ones who eat it up. They buy it for their sons,” he laughed.

He became convinced that as long as the message and substance are pure, and the meaning is something that truly reflects the faith, Catholics can handle a little hard-core imagery. In fact, they’ve been doing it for millennia.

War cry

At the same time, he’s wary of crossing the line into some of the hyper-masculinized versions of Catholicism that have become trendy in some quarters. The name of his business, Baritus, means “trumpeting” or “war cry,” and he does sell a popular sticker, a quote from Job that says “The life of man upon earth is warfare.” But he shies away from what he calls more gimmicky depictions of strength and virility.

“I love bourbon, but the bourbon, cigars, and working out [lifestyle] … all that stuff is fine, but that’s not what makes you masculine,” he said.

“I’m a man; I want to lead my family; I want to protect my wife and kids. All that stuff is inherent in the fact that I want to follow Christ. I’m supposed to die for my family,” he said.

But sometimes dying for his family looks like exercising the discipline to hit a deadline for a client, when he’d rather work on a personal piece that’s more exciting at the moment.

Lewis said that he thinks what makes him more manly in life is getting up every day and doing things he doesn’t want to do.

“Inspiration comes and goes in intervals, but when the heat is on to finish a project, I just have to check my desires and work on the fun thing when I can, and earn it. I have five kids who constantly want to eat,” he said.

Fortitude and persistence

He has tried to portray this difficult, daily pursuit of fortitude and persistence in his art. His image of St. Peter shows him downcast, tied up with rope, but clinging to the keys of the kingdom of heaven, and to a scroll of holy Scripture.

Lewis hopes that his striking, compelling images will work as a tool of evangelization in a world that’s starved for beauty.

“Putting them on phone cases and stickers is a good way to take the culture we have inside the doors of the Church and putting it out in to the world,” he said.

Catholics want to show off their faith and evoke conversations with other people, he said, but they aren’t likely to have much success by just going up to people and making their best arguments. Instead, just introducing them to beauty can open doors, just as it did for him.

But here, too, there is a line he will not cross. He makes digital art but is repulsed by AI-generated art and saddened to see Catholic businesses using it to save money, rather than hiring artists.

“I feel like the shoemaker at the dawn of the industrial revolution. I’m working on this craft, and now there’s a machine doing it for me at a million times the speed, and it’s accessible to everybody, and that’s a daunting place to be,” he said.

Uniqueness of the work

He only hopes that people will recognize and value the uniqueness of his work.

“[AI generated art] seems so divorced from what art is supposed to be. It’s masquerading as art. It doesn’t seem like there’s the control of the human mind behind it,” he said.

He believes that the question of AI-generated art is actually a spiritual one, that speaks to what it means to be human, because it concerns our ability to think and create, and not merely the end product.

He may use a computer to create his work, but, he said, “There’s still me behind it. There’s still the intent to convey the truth. With AI, it’s an algorithm. “

He urges people to consider what they are giving up when they replace human beings with algorithms, and to take the long view.

“In 50 years, what are the effects going to be? I encourage Catholics to support other Catholics,” he said.

Preserving what is good, even when it’s hard, is what Catholics have always done.