“For with you is the fountain of life, and in your light we see light” (Psalm 36:10).

The Cosmopolitan Club of Huntington, Indiana, was chartered 130 years ago, on January 18, 1894, which makes it one of the oldest extant discussion societies in the country. The papers delivered by its members range from the mundane to the divine, the sublime to the ridiculous, but every one is thought-provoking.

For a recent paper, one member took the first item of the Rotary Club’s famous Four-Way Test (“of the things we think, say or do”) as a starting point. “Is it the TRUTH?” implicitly assumes that there is such a thing as truth (and not just because Rotary invariably presents the word in ALL CAPS) and that it is something that we can know. Yet, as Tom Mills, the author of the paper, pointed out, even all of us who believe that truth exists and that we can know it may have different ideas of how we come to know the truth, and those ideas inevitably affect what we think the truth is.

Tom did an admirable job laying out the four most common theories of what truth is (and how we come to know it), but, perhaps because of my extensive reading over the last year of the works of Owen Barfield (the philologist/philosopher friend of C.S. Lewis and J.R.R Tolkien) and, more recently, The Sunday Sermons of the Great Fathers (an indispensable collection of commentary on the Gospel readings of what we now call the Old Calendar but which was, in both West and East, the standard lectionary throughout most of the 2,000 years of Christian worship), I realized as he was speaking that all of these theories are post-classical and — more importantly — post-Christian.

Truth, from the inside out

At the risk of oversimplifying, we can say that, in both the classical and the Christian understanding, we know the truth from the inside out, from the soul rather than from the senses. In his seminal work, History in English Words, Barfield documents, through the changing meaning of words, how human consciousness has evolved over time. The idea that truth is something external, something we can know only through deduction from the information we gather through our senses, took hold in the nations of the West at the time of the Reformation and the early days of modern science. The very evolution of the meaning of the word science — which once signified the body of all human knowledge (including philosophy and theology) and now is largely restricted to a method of empirical observation and testing — provides some sense of the revolution in consciousness that occurred at that time.

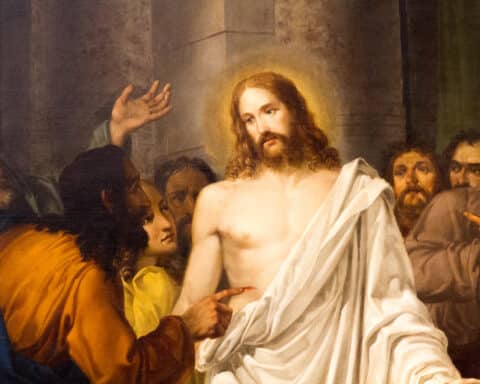

In the wake of that revolution, it is harder for us to understand the language of Scripture and the exegesis of the Church Fathers, because we are looking at the world through a different lens. So, for instance, in “the search for the historical Jesus,” we turn to astronomical calculations to try to determine what conjunction of planets and other celestial bodies might have appeared to the Wise Men as a star of immense brightness, portending the birth of a king, and, when we do not find such a phenomenon around the time of the birth of Christ, we say that he must have been born, say, six years before or three after, because then the planets were so aligned. That such reasoning — that the date when Christ was born must depend on the alignment of planets — sounds more like astrology than astronomy should be a warning sign, but we rarely heed it.

Scriptural consciousness

Yet when we turn to the Fathers of the Church, who lived in a time when astrology was an active pursuit, we see no such obsession with whether the stars were aligned at the time of Christ’s birth. Instead, they say simply that the star was Christ. By that, they do not mean that it wasn’t a real phenomenon, much less that we should worship a star, but that the star appeared when Christ was born because there is an essential unity between the star and Christ himself. Christ is our light, and in his light, we see light, and the light that appeared to announce the birth of the Light of the world is the light of Christ himself.

As C.S. Lewis wrote, “All contemporary writers share to some extent the contemporary outlook — even those, like myself, who seem most opposed to it.” There are many reasons to read the Fathers of the Church, but the most important is that they, unlike we, shared the consciousness of those who wrote the Scriptures.