“You got a fast car. I got a job that pays all our bills. You stay out drinking late at the bar. See more of your friends than you do of your kids.”

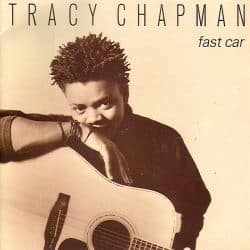

You may recognize the lyrics to the popular 1988 song by Tracy Chapman, “Fast Car.” It’s back in rotation and Luke Combs, who is currently successfully covering it, got to sing it with Chapman at the Grammys in recent days. He grew up listening to it, and you could see his love for it as he mouthed the words as she sang her parts.

I didn’t watch the Grammys, but it was hard not to check in on the performance at some point after. I noticed people on the right and left talking about it. It’s a human story about looking for meaning and having hope and wanting better. It’s about at least one partner wanting to work hard for the sake of their flourishing. At first the woman and man. And then the family.

“I’d always hoped for better,” the lyrics explain at the end. “Thought maybe together you and me’d find it. I got no plans, I ain’t going nowhere. Take your fast car and keep on driving.”

“I had the feeling I would be someone” are the most brutal words of the song. I can’t help think of the loneliness and suicide and the young mothers who all too often have never had a birthday celebrated for them.

A missed opportunity for unity

For a moment I thought that loving the performance of “Fast Car,” for those who watched, was a potential moment of cultural unity. Then I happened upon a columnist in the Boston Globe explaining how the song has different meanings now than when Chapman first wrote it based on her own experience of being raised by a single mother.

“Listen to the song today, and you’ll hear the plaintive cry of a young trans person trying to leave a state infested with codified hate;” she explained, “a woman forced to travel far from home to make the best decisions for her life and body; or a teacher pushed out of a beloved career for sharing with her students a book arbitrarily deemed inappropriate.”

Inasmuch as the song is about pain, okay. But the song is about a woman looking for something better and being failed by a man who doesn’t — perhaps because of being failed by his own father — step up to the plate. She wants more. And she thinks what he presents as love will make the difference if they work hard enough together.

The story is the reason women feel forced to abort their children. The story is the reason men aren’t held to the expectation not to use women and to become husbands and fathers when a child arrives on the scene — unborn at first and, if he or she gets the opportunity, born.

We have a decision to make

The beginning of the song should draw us to the hearts of innocent women — and men — who suffer — who have love in their hearts but haven’t had the examples of living that love sacrificially. In the song, we hear about a mother who left, a father who drank and a daughter who took care of him because of her motherly heart — even as a child dropping out of school to take on duties beyond her years.

What does it say that a mainstream reaction to rehearing the song is to say: Make sure women can get abortions on demand and children can get hormone blockers? How about helping families flourish? How about providing women with what they need to be the mothers they already are? How about letting her know that she is someone and that we love her enough as Christians and neighbors and fellow citizens to do everything in our power to help her see that she is someone — someone worth our time and more?

I don’t drive (I was born in New York City, and it’s a thing), but if I had a fast car, I’d want to use it to help more women who are dreaming about something better, looking for love in all the wrong places, perhaps, because how would you even know where to start in many circumstances? Of course, you don’t need a fast car. All you need is a heart and a willingness to open it to the kind of radical hospitality that Jesus showed us.

“We’ve gotta make a decision,” Chapman sings. We need to start on a new road or we may find ourselves answering to God for some things. That we did and didn’t do. It’s not just about abortion or the child abuse of our young that is trans-ideology, but simply loving one another more deeply with the heart of Christ in every encounter.