Warning, the following essay contains spoilers for those who have not seen the final few episodes of “Better Call Saul,” the last of which aired Aug. 15.

“I can say with complete self-confidence,” declares theologian Stanley Hauerwas in his memoir, “Hannah’s Child,” “that we are subtle creatures capable of infinite modes of self-deception.” Hauerwas might be describing one of the central moral themes in the recently concluded television series “Better Call Saul,” the extraordinary prequel to the exquisite series “Breaking Bad.” “Better Call Saul” is, among other things, a sustained meditation on the problem of self-deception, the process of self-discovery and the redemptive power of transparency and accountability.

The real name of the show’s protagonist, Saul Goodman, is James M. McGill, or “Slippin’ Jimmy” when, as a young man, he was pulling off small-time scams and cons in his native Chicago. We first get a hint of his transition to Saul Goodman in “Breaking Bad” when an anonymous accomplice in one of those grifts asks Jimmy his name. “Saul,” he responds, as in “S’all good, man.”

After Jimmy’s older brother, legendary New Mexico attorney Charles (“Chuck”) McGill rescues Jimmy from a conviction for a more serious crime in Chicago, Jimmy moves to Albuquerque, taking a job as a mail clerk in Chuck’s law firm, Hamlin, Hamlin and McGill. As children, underachieving Jimmy was always in the shadow of overachieving Chuck. So, unbeknownst to Chuck, Jimmy studies law at night online and, after a few failed attempts, passes the New Mexico bar exam. Jimmy was trying to be like Chuck but also to impress his brilliant older brother. Jimmy immediately seeks a job at HHM, but Chuck, while telling Jimmy he will support his application, goes behind Jimmy’s back to another partner, Howard Hamlin, to prevent Jimmy from working as an attorney for the firm. Jimmy learns of the deception, and his bitterness toward Chuck begins a downward spiral that results in Chuck’s suicide and Jimmy’s disbarment.

Moving among three distinct time periods, “Better Call Saul” is the story of Jimmy’s reinstatement to the bar, after which he eventually becomes the erstwhile attorney for, and partner in crime with, Walter White and Jesse Pinkman from “Breaking Bad.” In real time, as “Better Call Saul” opens, Saul is known as Gene Takovic, the manager of a Cinnabon store in Omaha, Nebraska, where he had fled from the law at the end of “Breaking Bad” when Walter White’s drug empire collapsed. Gene lives a mundane, anonymous life in Omaha until his identity is discovered by a taxi driver who recognized him from his days as a notorious attorney and, subsequently, a fugitive from Albuquerque. The story of Jimmy’s reinstatement to the bar and second career as an attorney is told in flashbacks from the Omaha storyline, to which “Better Call Saul” returns in the few last episodes.

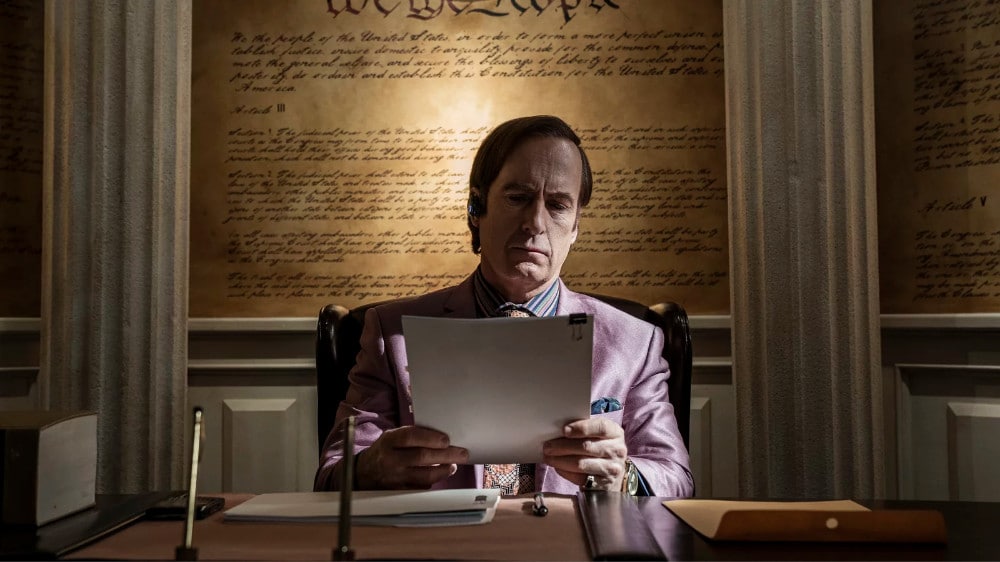

When he is reinstated as an attorney through a disingenuous manipulation of a panel of bar representatives, Jimmy adopts the name Saul Goodman, reprising the line from his Chicago grifting days. In doing so, Saul begins a path of attempted self-deception that leads to his ultimate demise. Partly, he wants to separate himself from his famous brother, Chuck, by shedding the name McGill. He could, he thought, take a new identity, unencumbered by the legacy of both Chuck’s success and suicide. The new name is also an attempt to deceive himself that he could exist on both sides of the law, complicit in the very crimes for which he represented his defendant clients. And, as he rationalized to Walter White in “Breaking Bad,” his name change was an attempt to deceive himself that his name was more attractive to the criminals whose clientele he sought. Jimmy is capable of “infinite modes of self-deception,” in Hauerwas’s words.

When Saul fled to Omaha, the self-deception (this time imposed by the circumstances) continued, as Gene Takovic attempted to deceive himself that he could live a new mundane life but pine for his prior existence as the brazen Saul Goodman. And this was the self-deception that led both to his ultimate demise and probably redemption. After his identity was discovered, Gene/Saul was arrested in Omaha and extradited to Albuquerque for his many crimes in “Breaking Bad.” While he was exposed to a possible life sentence plus 190 years in prison, Saul faked, dodged and deceived to negotiate an agreement for seven and a half years in exchange for a guilty plea to two of the lesser counts.

But when Saul’s ex-wife, Kim Wexler, appears at the hearing to approve the plea agreement, something happens to Saul that is unexpected but not improbable. Wexler, herself, had made an earlier confession of complicity with a scheme to discredit another attorney, which led to that attorney’s unexpected murder. Wexler’s was an egregious moral failure, but not a crime that approached the seriousness of Saul’s, which included complicity after the fact to the murder of two federal agents. But Wexler’s confession and appearance affected a redemptive turn in Saul. And key to the redemption was his abandonment of the attempt at self-deception.

Declaring to the judge that his name was James McGill, Jimmy confessed to his crimes with Walter White, repudiating and contradicting the sworn statements he had given in his plea negotiation. As expected, this resulted in the government revoking the agreement, and the court imposing a sentence of 86 years in a maximum-security prison.

After the quote above, Stanley Hauerwas goes on to explain, “You learn who you are only by making yourself accountable to the judgment of others.” Among its many attributes, “Better Call Saul” is a brilliant illustration of both the truth and the redemptive possibility of this accountability. James M. McGill (aka, Saul Goodman; aka Gene Takovic) could only be redeemed when he stopped trying to deceive himself. And he could only stop deceiving himself by making himself accountable to the victims of his crimes and the judgment of the court.

In the closing scene of “Better Call Saul,” Jimmy watches Kim exits the prison after a visit to him. But while he will never escape the bars of the prison, one believes that James M. McGill found redemption in making himself accountable to the judgment of others. And therein lies a powerful moral lesson in this remarkable television series.

Kenneth Craycraft is the James J. Gardner Family Chair in Moral Theology at Mount St. Mary’s Seminary and School of Theology in Cincinnati.