When the much-anticipated Britney Spears autobiography, “The Woman in Me,” was released in Oct. 2023, her long-time fans were eager to hear from her. After all, Spears had been essentially silenced for more than a decade due to her father’s controversial conservatorship over both her person and her estate, and the book promised that she could finally share her story.

The book chronicles her rise to fame, first as a cast member on the “Mickey Mouse Club,” then as a recording artist.

But what grabbed the headlines was not her difficult childhood, her music, or even the allegedly erratic behavior that is said to have ended her third marriage.

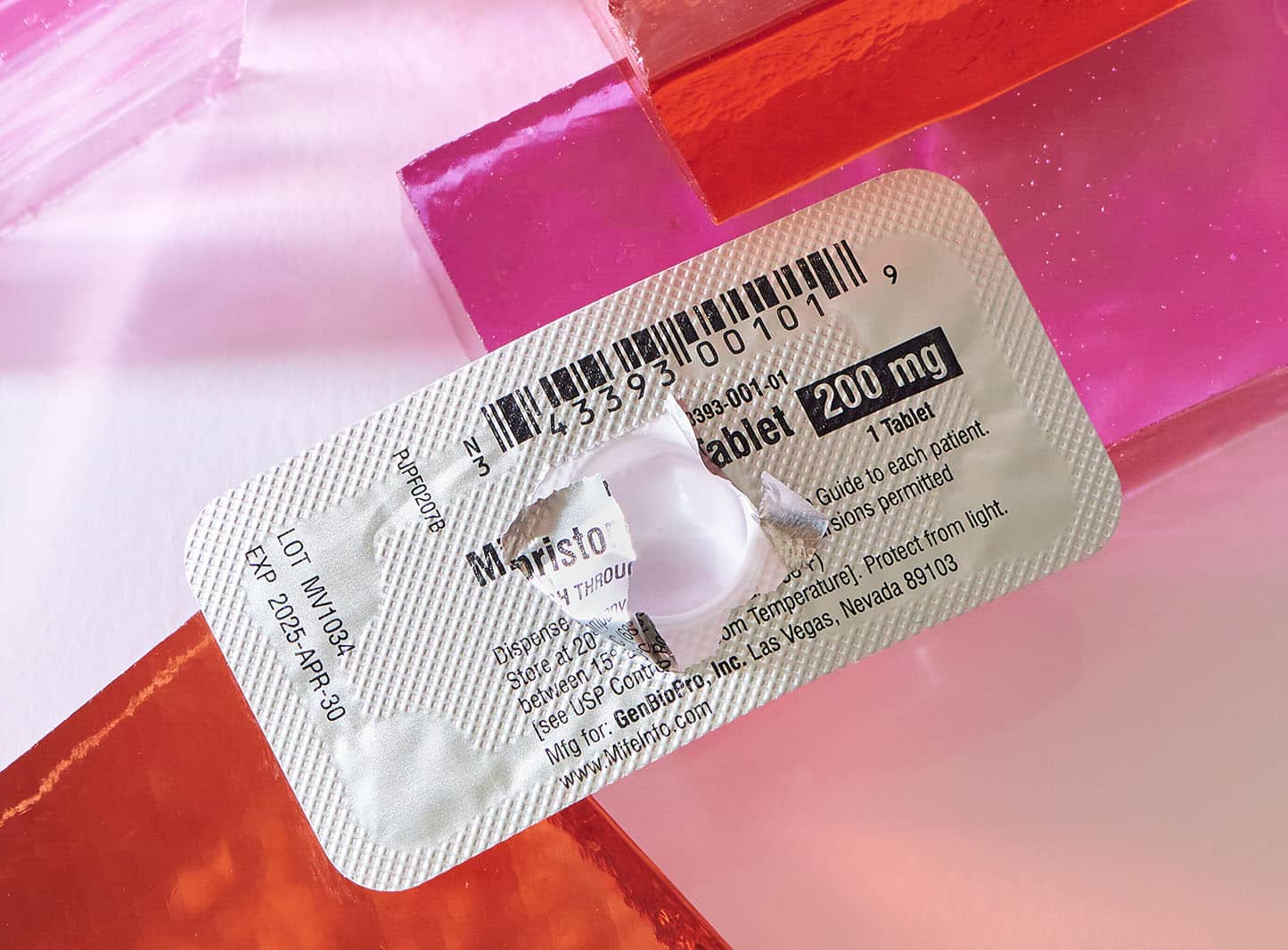

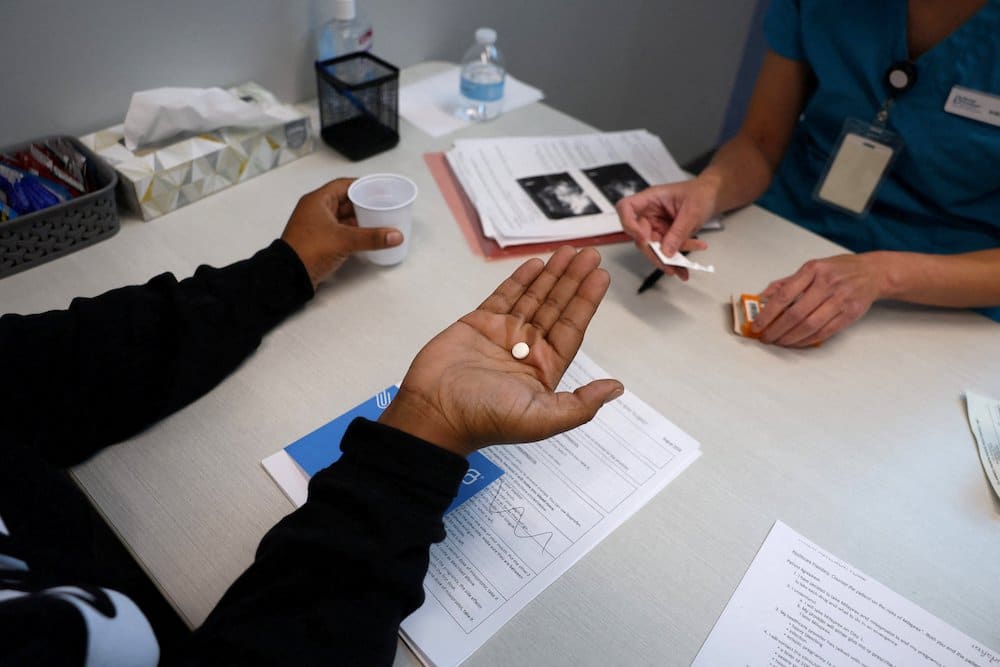

It was her abortion — specifically, her use of the abortion drug combination mifepristone and misoprostol. According to the American Academy of Pro-Life Obstetricians and Gynecologists (AAPLOG), mifepristone (sold by Danco under the brand name Mifeprex), is a “progesterone receptor antagonist” — essentially, an antiprogestin, a synthetic steroid that prevents the nutrients necessary for growth to reach the developing baby, eventually causing death. The second drug in the regimen, misoprostol, induces intense uterine cramping to expel the remains.

“To this day, it’s [the abortion] one of the most agonizing things I have ever experienced in my life.”

— Britney Spears

Spears’ book revealed that during her four-year relationship with fellow former Mouseketeer Justin Timberlake, she had become pregnant and that, under pressure from Timberlake, she used the pills at home to end the life of her unborn child. “If it had been left up to me alone, I never would have done it,” Spears wrote. “To this day, it’s one of the most agonizing things I have ever experienced in my life.”

Mifepristone comes to the U.S.

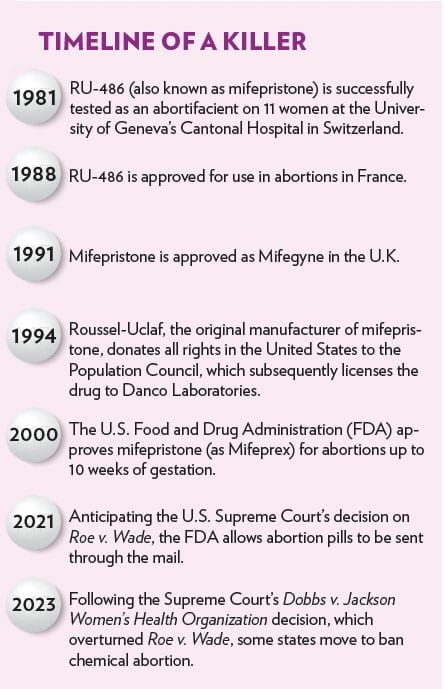

At the time of Spears’ abortion in 2000, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) had recently given expedited approval to so-called medication abortion, a two-drug cocktail that causes the death of the unborn child and then miscarriage. The first of the two abortion-inducing drugs is mifepristone, developed by the French pharmaceutical company Roussel Uclaf in the 1980s. Also known as RU-486 (the name of the company’s chemical formulation for the drug), mifepristone was approved by the French government for the purpose of ending pregnancy in September of 1988.

Roussel Uclaf did not initially seek to market the drug in the United States, wanting to avoid the highly controversial issue even then shaping American politics. But that changed once President George H.W. Bush left office and President Bill Clinton was elected. Making RU-486 available to American women was a priority of the Clinton administration, and great pressure was brought to bear on the company to share the rights to produce the drug in the United States. The Washington Post reported at the time that Roussel Uclaf company spokesperson Lester Hyman testified at congressional hearings on RU-486 that “then-President Bush spoke stridently against any procedure that would result in early pregnancy termination. … It was only when President Clinton changed the governmental policy and specifically asked Roussel to make the procedure available here that it, out of respect for the president of the United States, agreed to make every effort to comply with his request.”

With fewer than 20 employees, [Danco Laboratories] is a company shrouded in secrecy. Danco uses a P.O. Box instead of a street address and does not disclose the identities of its directors nor the profits it makes each year from medication abortion.

Although the company had indicated it would only give the RU-486 patent directly to the U.S. government, political advisors to Clinton suggested that move might be too controversial, even for a president as stridently committed to the abortion issue as Clinton. Then-HHS Secretary Donna Shalala persuaded the parties negotiating the issue with an unusual solution — Roussel Uclaf could, she suggested, give the patent to the Population Council, a population control organization founded by social activist John D. Rockefeller III in 1952, grandson to to the nation’s first billionaire.

In turn, the Population Council would give the exclusive license for mifepristone to a pharmaceutical company created for the sole purpose of producing the abortion pill, Danco Laboratories. (Danco now markets the drug under the brand name Mifeprex.) With fewer than 20 employees, it is a company shrouded in secrecy. Danco uses a P.O. Box instead of a street address and does not disclose the identities of its directors nor the profits it makes each year from medication abortion. It does not create, market or sell any drug other than Mifeprix.

Mifepristone fast-tracked to approval

The FDA’s approval of mifepristone was politicized from the very beginning.

Once the Clinton administration had the product license and manufacturer in place, all that was left to put the drug on the American market was to obtain FDA approval.

It did so within six months, an extraordinarily expedited turnaround time for what even the Population Council’s attorney called “a serious medical procedure.”

To quickly green light mifepristone, the FDA used an accelerated approval process known as “Subpart H.” Prior to the approval of mifepristone, only 40 drugs had qualified for the “H” designation, as it is designated specifically for medications that “treat serious or life-threatening illnesses.” Although pregnancy is the natural and healthy response of a female body to sexual relations (by contrast, infertility is a sign of illness), the FDA nonetheless declared that mifepristone treated a “serious or life-threatening illness” alongside grave conditions like HIV/AIDS, cancer and hypertension.

The FDA’s 2000 approval, however, implicitly acknowledged the risks of mifepristone to women by placing safety requirements on its use. These restrictions included mandating that only physicians could prescribe the drug, imposing a seven-week gestational limit, and requiring the pregnant woman to participate in three separate in-person physician office visits — the first, so the doctor could personally administer the mifepristone; the second, three days later, to personally administer the misoprostol to induce the uterine cramping; and the third at approximately two weeks post-abortion to confirm that no fetal body parts or pregnancy tissue remained in the uterus and to confirm that bleeding had subsided. Finally, the FDA also required providers of the abortion pill to report all adverse health events, like infection or excessive bleeding — not just deaths.

Major changes in 2016

In 2002, the AAPLOG, along with the Christian Medical & Dental Associations (CMDA), filed a citizen petition with the FDA, challenging the 2000 approval. Although the FDA should have responded within 180 days to the petition, the agency instead waited for 14 years before issuing a formal rejection in 2016.

That same day, in the waning months of the Obama Administration, the FDA announced they had approved “major changes” to the use of mifepristone that removed the restrictions it had imposed in 2000. The “major changes” eliminated the requirement for both follow-up appointments — the first that required misoprostol to be administered in person and the second that had ensured that fetal remains were not still present in the woman’s uterus. The dosage directives were changed, as was the prohibition on non-doctors prescribing and administering mifepristone. The FDA also increased the gestational age limit of the unborn child being aborted from seven to 10 weeks and completely eliminated the previously required “non-fatal adverse event reporting” — meaning that only deaths from mifepristone would be reported, not injuries to the woman — even serious ones.

In 2019, a new citizen petition was filed, once again by AAPLOG, but this time joined by the American College of Pediatricians (ACPeds), which had expressed additional concerns about the potential developmental impact of hormone-blocking drugs like mifepristone on teenage girls. In 2021, that Citizen Petition was also rejected.

Further changes brought on by COVID-19

Enter COVID-19. During the pandemic, the FDA did not enforce the only in-person appointment required to dispense mifepristone because of the “shelter in place” orders operative in so many states. After the election of President Joe Biden, the agency permanently dropped the in-person appointment requirement altogether, allowing women to receive the abortion drug through the mail.

Consequently, in November of 2022, various pro-life medical associations led by the Alliance for Hippocratic Medicine, along with pro-life physicians in their individual capacities as doctors, filed a federal lawsuit in the U.S. District Court for the Northern District of Texas, alleging that “the FDA failed America’s women and girls when it chose politics over science and approved chemical abortion drugs for use in the United States. And it has continued to fail them by repeatedly removing even the most basic precautionary requirements associated with their use.”

In addition to stating concerns about the expedited process used to approve the drug, the case, Alliance for Hippocratic Medicine v. U.S. Food and Drug Administration, also took issue with the Biden Administration’s FDA ruling “that it would permanently allow abortionists to send chemical abortion drugs through the mail.”

The potential of mail-order abortion drugs to facilitate sex trafficking is a real concern, as are instances of forced or coerced abortion.

“This decision not only harms women and girls who voluntarily undergo chemical abortions, but it also further helps sex traffickers and sexual abusers to force their victims into getting abortions while preventing the authorities from identifying these victims,” the plaintiffs noted, and “failed to acknowledge and address the federal laws that prohibit the distribution of chemical abortion drugs by postal mail.” This particular statute, known as the Comstock Act, is current and enforceable law, yet the FDA’s decision completely sidestepped it.

The potential of mail-order abortion drugs to facilitate sex trafficking is a real concern, as are instances of forced or coerced abortion. Additionally, making mifepristone pills available without any verification of gestational age allows for abortion well beyond the current 10-week gestational limit, increasing the risk for the women who take them. The recent case of Nebraska teenager Celeste Burgess serves as a cautionary tale. Celeste was 29.5 weeks pregnant when her mother, Jessica, obtained abortion pills through the mail for her. The then 17-year-old gave birth to a stillborn child in the shower and then, along with her mother, attempted to destroy the child’s body in violation of state law that prohibits human remains from being desecrated or buried in an area other than a cemetery. (She eventually pled guilty to concealment of a corpse and was sentenced to 90 days in jail.)

The fight to withdraw mifepristone’s approval

The pro-life medical associations and doctors asked the district court to issue a preliminary injunction ordering the FDA to “withdraw or suspend” not only its initial 2000 mifepristone approval but also the subsequent 2016 changes and the removal of the in-person dispensing requirement for mifepristone.

The district court agreed. In a 67-page opinion, Judge Matthew Kacsmaryk (scrutinized by media outlets even before his decision had been issued for his religious beliefs) halted the FDA’s approval of chemical abortion drugs as well as the removal of the initial safeguards.

Tellingly, he was strongly criticized by left-leaning commentators for using the words “unborn child” in his opinion, rather than the clinical descriptions of “embryo” or “fetus” or the increasingly favored term by supporters of legal abortion, the dehumanizing phrase “products of conception.” In a footnote, Kacsmaryk explained: “Jurists often use the word ‘fetus’ to inaccurately identify unborn humans in unscientific ways. The word ‘fetus’ refers to a specific gestational stage of development, as opposed to the zygote, blastocyst, or embryo stages. … Because other jurists use the terms ‘unborn human’ or ‘unborn child’ interchangeably, and because both terms are inclusive of the multiple gestational stages relevant to the FDA Approval … this Court uses ‘unborn human’ or ‘unborn child’ terminology throughout this Order, as appropriate.”

In a surgical procedure, the abortion provider performs the abortion. But in a medication abortion, the woman having the abortion is the moral agent — she obtains and takes the pills, almost always in her own home, and then passes the unborn child’s remains and then must dispose of them herself.

He was also critiqued for meticulously detailing the physical harms that chemical abortion drugs cause to women and for noting that women who undergo a medication abortion are more likely to present in an emergency room after taking the pills than a woman who has a surgical abortion. A patient with a history of a previous C-section, for example, should not take abortion pills due to the possibility of uterine rupture. Other adverse outcomes, like sepsis caused by the retention of embryonic or fetal tissue or fallopian tube rupture in a woman who has an ectopic pregnancy (a pregnancy outside the uterus), can even be life-threatening. It is because of those potential complications that the FDA required the in-person dispensing and oversight of medication abortions when it first approved mifepristone in 2000 — to minimize potential adverse outcomes for pregnant women. And the medical contraindications for women increase as the pregnancy proceeds; the later in pregnancy mifepristone is used, the greater the danger.

A distinct difference between a medication abortion and a surgical abortion is the participation of the woman in the act itself. In a surgical procedure, the abortion provider performs the abortion. But in a medication abortion, the woman having the abortion is the moral agent — she obtains and takes the pills, almost always in her own home, and then passes the unborn child’s remains and then must dispose of them herself. The district court opinion acknowledges this reality, along with the emotional distress it can cause: “Women who have aborted a child — especially through chemical abortion drugs that necessitate the woman seeing her aborted child once it passes — often experience shame, regret, anxiety, depression, drug abuse and suicidal thoughts because of the abortion. … Many women also experience intense psychological trauma and post-traumatic stress from excessive bleeding and from seeing the remains of their aborted children.”

The case arrives at the Supreme Court

Judge Kacsmaryk scheduled the court order to go into effect in seven days, to give the Biden administration time to appeal. Three days later, the Department of Justice filed an emergency motion with the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 5th Circuit, asking the appeals court to keep the district court’s order from going into effect.

A unanimous panel of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 5th Circuit kept in place a portion of Judge Kacsmaryk’s order, ruling that abortion providers could no longer distribute abortion drugs by mail, restoring the seven-week gestational age limit for chemical abortions and reinstating the mandatory doctor visit and requirement to follow up to make certain women were not experiencing complications.

In September, the Biden administration and Danco, the drug manufacturer, petitioned the Supreme Court, which hit the pause button on the entire process, allowing the Biden administration to ask the Court for a “writ of certiorari” — a request that the Supreme Court settle the matter. On Dec. 13, the Court announced that it has agreed to hear arguments regarding the FDA’s decisions in 2016 and 2021 to remove the safeguards around the abortion drug medication, as well as whether or not the medical groups and doctors involved were entitled to bring their case in the first place. But the court declined to hear arguments regarding whether the initial FDA decision in 2000 was proper.

The Court has yet to set a date for oral arguments in the case Food and Drug Administration v. Alliance for Hippocratic Medicine (No. 23-235). As pro-lifers await the Court’s ruling, they should take up the cause of educating themselves and others on the potential dangers of the drug. For too long, women have been put at risk by medicine that masquerades as health care. The Supreme Court ruling, which has great potential to reject this false and dangerous narrative — will be one to watch, and one to pray for.