In John’s Gospel, the suggestion is that the reason some people didn’t believe in Jesus was because they sought their own glory more than the glory of God. That is, because they sought praise more for themselves, seeking thereby the esteem of others more than God’s esteem, they were spiritually blind, unable to see the Christ standing right in front of them.

Twice Jesus suggests this. First at the beginning of his earthly ministry: “How can you believe, when you accept praise from one another and do not seek the praise that comes from the only God?” (Jn 5:44). And then near the end, just as the hour of his Passion was to begin: “Nevertheless, many, even among the authorities, believed in him, but because of the Pharisees they did not acknowledge it openly in order not to be expelled from the synagogue. For they preferred human praise to the glory of God” (Jn 12:42-43).

| November 5 – 31st Sunday in Ordinary Time |

|---|

|

Mal 1:14–2:2, 8-10 Ps 131:1, 2, 3 1 Thes 2:7-9, 13 Mt 23:1-12 |

Such was the blindingly precarious arrogance with which Jesus had to contend. People worried more about what others thought of them than what God thought of them; thus, as a result, they couldn’t really see God at all. That’s why Jesus said to some Pharisees, after healing the man born blind, that since they presumptuously said “‘We see,’ so your sin remains” (Jn 9:41).

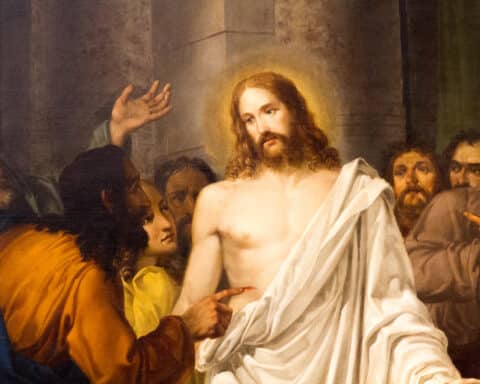

This is the spiritual blindness and arrogance Jesus (to call it what it is) attacks at the end of the Gospels. Jesus is done arguing; up to this point, he has argued with Pharisees, scribes and Herodians about everything from the resurrection of the dead to taxes. But nothing’s come of it. No one really won; it’s just that no one dared to ask him any more questions (cf. Mt 22:46).

Truth to power

At this point, Jesus, to use contemporary parlance, speaks truth to power. Do not follow their example, he says. They preach but do not practice, he says. It’s all a performance; they want to be seen, he says. All they want is the honor in the marketplace and in the synagogue (cf. Mt 23:3-7). “Woe to you,” Jesus will say almost in the same breath (cf. Mt 23:13-36). Gentle diplomacy is not Jesus’s game here. He’s telling it like it is. This is the Christ who’s come to see his own Temple’s corruption, who knows the violence burning in the hearts of so many surrounding him. Perhaps we can forgive Jesus in this instance for not being as nice as we normally like him.

Such is the context of Jesus’s excoriation of those who use the titles of “rabbi” or “father.” If what these titles do is create cultures wherein people prefer honors given by humans to the honor of God, then yes: these titles are a problem and should be scrapped. This plainly is the view of Matthew’s Gospel, and it does indeed make sense. We Catholics, with all our titles and all our reverend fathers, shouldn’t hide from this or try to tame it by means of clever interpretation. Rather, we should learn from it, think about what we’re doing, and then rediscover the spiritual truth of what we do. Otherwise, we’re no different from those Jesus called hypocrites.

Clearly, the tradition represented by Matthew’s Gospel didn’t win the day. Long have Christians called spiritual mentors and some clergy “father.” Perhaps this goes back even to Paul (cf. Timothy and Onesimus whom he called his “sons”). Why this is so is beyond our discussion. But the moral remains; the danger of such titles remains. That’s what we should take away: the warning Jesus gives about such titles. We should take care they don’t render us spiritually blind.

Indeed, I’m in very good Catholic company saying we should pay attention here. Read, for instance, St. Gregory the Great’s “Pastoral Care.” The beginning of it is full of such warnings, mostly about prideful and arrogant clergy. “[S]ome there are,” he writes, “who aspire to glory and esteem by an outward show of authority within the holy Church. They crave to appear as teachers and covet ascendancy over others” (1.1). These are bad clergymen, St. Gregory plainly says. Such a bishop or priest “feasts on the subjection of others in the hidden reveries of his thought” (1.8). For St. Gregory, the spiritual dangers present in Matthew remain. This is the pressing lesson for us today, that such dangers remain for us too.

Hans Urs von Balthasar wrote once, “The priest is a servant from every point of view and a lord from no point of view.” Some of us priests and bishops could use to learn this lesson. Again, the point is simple; it’s about the spiritual dangers that attend pride, that come with caring about what others think more than caring about what God thinks. Don’t get caught up in silly questions here; learn the deeper lesson. And then humbly seek God, his praise alone.