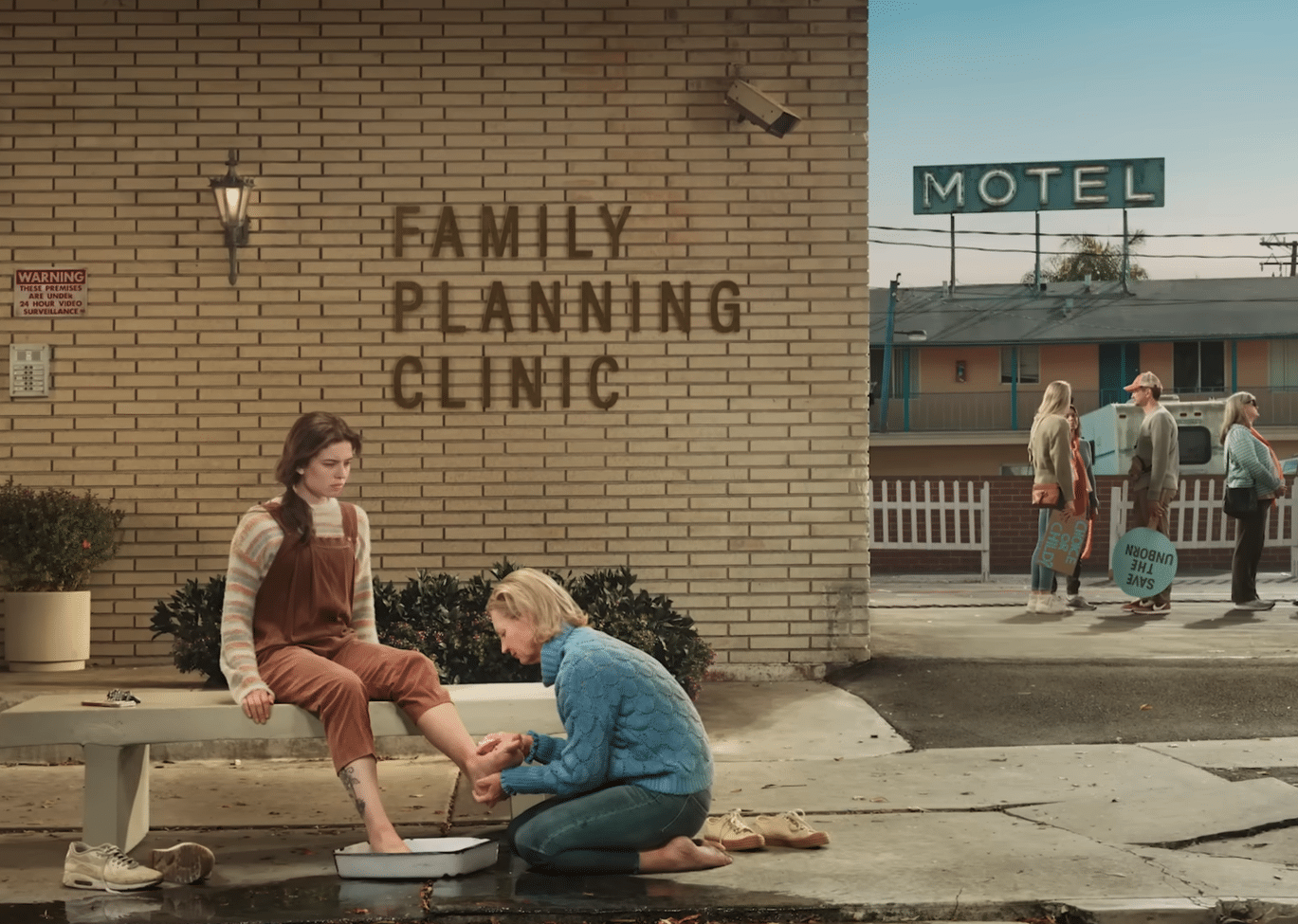

Among the ads at this year’s Super Bowl was one from the organization He Gets Us (HGU), the latest in a series of TV and social media videos that have appeared over the past few years. The 2024 Super Bowl ad features a series of still photographs of a wide variety of people washing the feet of others. No narrative or captions accompany the photos. Rather, at the end of the video, banner-style messages state, “JESUS DIDN’T TEACH HATE,” “HE WASHED FEET,” “He gets us. All of us.”

Of course, it is certainly true that Jesus gets us. It’s not at all clear, however, that He Gets Us gets Jesus. Indeed, it seems that the ads reduce the concrete particularity of Jesus Christ to a vague admonition to be nice and not to judge. Being nice and not judging others are good ideas. But you don’t need Jesus to know that. And knowing Jesus is much, much more. More to the point, being nice and not judging are not means of salvation.

Staged in various contexts, the Super Bowl ad features unlikely photos of people washing the feet of others who are portrayed as having disparate interests and perspectives. For example, an oil field worker washes the feet of an environmental activist against the backdrop of land riddled with oil drilling equipment; a rancher washes the feet of a native American; a woman washes the feet of another woman in front of a “Family Planning Clinic,” while anti-abortion protestors mill about indifferently in the background; an apparently non-Muslim woman washes the feet of an apparently Muslim woman, while the non-Muslim woman’s husband looks on suspiciously; an apparently Catholic priest washes the feet of a man in a caricature of an effeminate pose. And so forth.

What about salvation?

On its website, HGU provides a sympathetic account of the ad’s purpose. It is “built on the premise of Love and Unity.” They explain that Jesus’s washing of feet of the “12 disciples” (not “apostles”) is “a symbol for all of his followers to see how they should treat one another.” “Foot washing required humility on the part of both parties,” HGU continues, “the one willing to wash another’s feet and also the one willing to have their feet washed.” Thus, foot washing was “an act of mutual admiration. Jesus was shedding any notion of rank or caste among his disciples.”

While not an exhaustive analysis, this is not an illegitimate interpretation of the act of foot washing. And HGU is further correct in its explanation that “figurative foot washing” can take all kinds of forms, including simple gestures of kindness and charity. “Acts of kindness done out of humility and respect for another person could be considered the equivalent of foot washing.”

All of this is well and good. The problems lie in what HGU expects to accomplish by these ads and, more importantly, what they don’t say; indeed, what they implicitly deny.

Put in simplest terms, the ads seem to imply that being nice and nonjudgmental is the means of salvation rather than its effect. HGU advocates that people act like Christians. But its ads and website are completely devoid of the central Christian message that conversion to the person of Jesus leads to salvation, which leads, in turn, to the kinds of virtues HGU advocates. It reduces Christian virtue to tolerance and divorces tolerance from conversion and discipleship.

For example, foot washing in the Super Bowl ad is wholly disconnected from the Last Supper and its radical call to obedience to Christ. In this context, foot washing is inextricably tied to Jesus’ preparation for his sacrificial death and to his institution of the Eucharistic feast that perpetuates that death through time. In the Last Supper, Jesus is not admonishing his apostles to be nice, non-judgy people. He is commanding them to follow him. You would learn nothing of this from the ad or HGU’s interpretive essay about it.

The scandal of particularity

Nor is the particularity of conversion to Christ present in other content from HGU, either in its ubiquitous ads or explanations of its organizational purpose. HGU consistently encourages people to follow “Jesus’ teachings,” which “are a warm embrace, not a cold shoulder.” They very persistently invite their readers to “rediscover and share the compelling story of Jesus’ life.” The vague phrase “story of Jesus” appears over and over on HGU’s website. Nowhere, however, does the organization suggest that it’s not the story of Jesus, but rather Jesus himself who saves. HGU expressly states that their purpose is to “share an idea.” The problem, again, is that Jesus is not an idea. He is a living person who commands obedience.

He Gets Us expressly rejects this scandal of particularity. Rather than a call to conversion, HGU’s website explains, the organization “simply invites all to consider the story of a man who created a radical love movement that continues to impact the world thousands of years later.” But, as HGU concedes, there’s nothing particular about Jesus in all this. “All of us work together relentlessly to share the transformative power that unconditional love, forgiveness, and sacrificial generosity have to change us, our families, our communities, and our country.” This is a good idea. But I can get it from the editorial page of The New York Times, to crib a line from the late Father Richard John Neuhaus.

Nowhere does Jesus command, suggest, admonish or advocate that we are saved by embracing an idea. Rather, he declares, “I am the way and the truth and the life. No one comes to the Father except through me” (Jn 14:6). Transformation comes from conversion. No one is saved by “transformative power,” but rather by the life, death and resurrection of Christ.

He Gets Us doesn’t get Jesus. He did not create a “love movement.” He created a Church. And he did not teach that we can be saved by an “idea,” regardless how laudable it might be.