What symbols come to mind when you think of Ireland? Your list probably includes the harp, the shamrock and maybe the tri-color flag, but perhaps you think, too, of the Celtic cross, the ringed cross that is found in cemeteries, on football medals and in tattoos throughout Ireland and beyond.

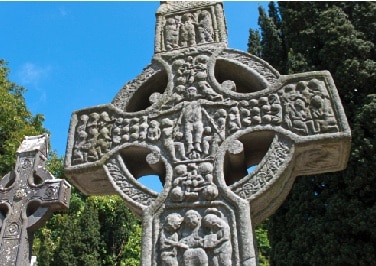

It’s a form of the cross that has ancient and mysterious roots. From the ninth century until the 12th century, huge stone crosses of this kind were carved and placed in monastery churchyards throughout Ireland, with scattered examples found also in Scotland, Wales and England. From a technical and artistic point of view, many of them are masterpieces, and it is very surprising indeed that they emerge suddenly, without any apparent antecedents before the year 800.

Depictions of biblical scenes

These crosses, carved either in sandstone or granite, and almost certainly brightly painted at the time, were known as “high crosses,” but, occasionally, one or other of them is referred to as a “cross of the Scriptures,” a name that points to one of their most fascinating features: As well as abstract decoration, they are often covered from top to bottom with biblical scenes. These scenes include Adam and Eve in the Garden of Eden, Noah’s Ark, Abraham’s sacrifice of a ram, the three young men in the fiery furnace, the flight into Egypt, the miracle of the loaves and fishes, and, of course, the crucifixion itself.

One of the more mysterious of these scenes simply depicts a man playing the harp. I’ve heard tour guides claim that this is a vague reference to Irish traditional music, but anyone with a solid biblical formation knows exactly who it is: King David.

In 1 Samuel, young David is introduced as not only a man of valor but also a gifted harpist, as Leonard Cohen reminds us: “Now I’ve heard there was a secret chord / That David played, and it pleased the Lord.” Tradition also ascribes to him the composition of many, if not all, of the 150 psalms in the Bible.

Pointing to the psalms

All this means that, when we find David playing his harp on any of the high crosses, we’re being invited to think of the psalms. In early Christian Ireland, of course, the psalms were absolutely omnipresent. All the little churches and hermits’ huts that dot the landscape would have been places of psalm singing. Everyone who was literate would have learned to read and write with the help of the psalms — one of the earliest fragments of writing from Ireland is the text of Psalms 30-32 written on wax tablets, apparently by someone learning to write.

We know quite a bit about how early Irish Christians interpreted the psalms, too. There’s a treatise on the psalter written in Old Irish about the same time as the first high crosses were being carved, and it claims there are four meanings in every psalm: the “first history” (cétna stoir), the “second history” (stoir tánaise), the “sense” (síens) and the “moral” (morolus).

The “first history,” according to this scheme, is how the psalm applies to the immediate context: David and his court. The “second history” involves the application of the psalm to later events in the history of Israel. The “sense” of the psalm is how it applies to Christ and the Church, and the “moral” is about the application of the psalm to our daily lives. So each psalm was read by early Irish Christians on these four levels: two levels in ancient Israel, then Christ and the Church, then my own personal life.

Christ-centered art

Of these levels, it’s clear that the really important one for these readers of the psalms was the “sense” — that is, what each psalm revealed prophetically about the coming Christ. The same Old Irish text on the psalms teaches that we can find prophetic hints in the psalms of Christ’s birth, his baptism, his death, resurrection and ascension, his return in glory, and so on.

This way of reading the psalms as referring to the life of Christ is a marked feature of Irish Christianity. Probably the oldest surviving Irish manuscript, for example, is the Cathach, a book of psalms. (It’s also the second oldest surviving manuscript of the psalms in Latin anywhere in the world). In this manuscript, above each psalm, is found a little sentence offering an interpretation of the psalm, and most of these “titles” point to the life of Christ. If you open a modern breviary to pray the Divine Office, you’ll find that this practice continues to this day.

The Irish didn’t invent this Christ-centred way of reading the psalms, though. It goes right back to the earliest Christian community. Think of Peter’s speech at Pentecost, in Acts 2, for example. Twice, he quotes a psalm to explain to the gathered crowds the significance of Jesus’ death and resurrection. On the cross, Jesus himself cries out the opening words of Psalm 22 – “My God, my God, why have you abandoned me?” — calling to the mind the whole story of that psalm, through desolation and into victory. And on the road to Emmaus, Our Lord explains the significance of his death and resurrection by appealing not only to the Law and the prophets, but also to the psalms (cf. Lk 24:44).

So if you ever come to Ireland, be sure to make your way to one of the ancient high crosses, and look out for David with his harp, a reminder of the long and holy tradition of reading the psalms in light of Christ, and reading the story of Christ in light of the psalms.

Father Conor McDonough, OP, is a lecturer in the Dominican House of Studies in Dublin and the coordinator of the online preaching projects of the Irish Dominican Province.