Dear Catholic parents,

A human being’s first culture is his or her mother’s womb. We usually think of culture as having a formative influence on us — for good or ill — and this is true, in spades, of a mother’s womb. It is not only the place where nourishment and protection are provided (or, tragically, lacking), but also where powerful influences shape how the child develops. One of the most powerful influences of all in the womb is the mother’s voice.

As Dr. Kristin Collier writes in the Church Life Journal, “The mother’s voice is reported to be the most intense acoustical signal measured in the amniotic environment. [Research] shows that babies not only recognize their mother’s voice in-utero, but they prefer it over all other voices. Research has also shown that the mother’s voice has the ability to affect her child’s brain structure, influence her baby’s heart rate and respirations, and is likely a key factor in her child’s development of language.” Mamma’s voice is part of the very space in which the child grows.

When we think of a family home, we should think in similar terms. As children are growing toward maturity, the family home is the most important and formative culture. If it is an intentional culture, then children are formed within and according to those intentions. If it is an unintentional culture, then they are formed unintentionally. One way or another, the culture of the home is a place and space of formation.

Culture

This is different than how we normally think about “culture.” We tend to think that “culture” is “out there,” in society, away from home. We worry about how “the culture” makes its way into the home, affects children at school or warps them through various media. We fall into assuming that there is only one culture in which we are all submerged in a given place at a given time and that the only thing to do is critically assess that culture and then, usually, resist what that culture offers. What is missing in that assumption is the realization that the more powerful culture is much closer to home — in fact, it is the home.

Just as the womb is the most intimate and powerful culture for the unborn child, so is the family home the most intimate and powerful culture for growth and development.

Shaping and nourishing children

If this is true, then the question is how to make the family home into the kind of culture we would want to shape and nourish our children. The answer to that question begins with thinking about space. What fills the space of the home, how those things are organized, and where attention is naturally drawn in a home are among the most important factors in fostering the culture of the home.

Consider this: Some years ago, I was making a connection at the Newark Liberty International Airport. This is not typically a place of bliss. I was surprised, though, when I walked into a new terminal that had recently opened. It was bright, and everything was shiny. I found a seat at a bar to order some food and an adult beverage. Instead of talking to the bartender, though, I found before me a tablet. I ordered and paid via the tablet, then I had the option of finding something to watch, read or play on the tablet. I looked around: every seat at the bar had a tablet, as did every table in the restaurant. The same was true of just about every seat at every gate in the terminal. I don’t remember anything else about that day passing through the airport: all I remember is the garden of tablets. It is very obvious what that space was inclining and expecting people to do: engage all things through the tablets.

| READ MORE |

|---|

|

This is the second in a series of letters written to Catholic parents in which Leonard DeLorenzo will offer advice on raising healthy, happy, faithful children. Read the first letter here. |

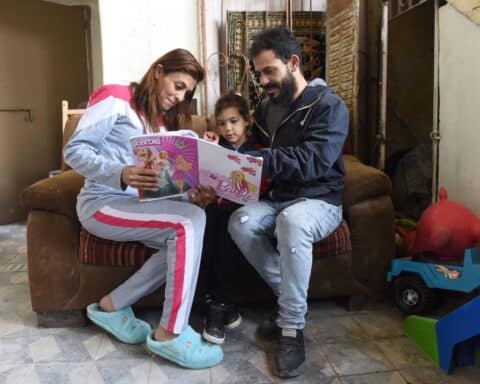

Here’s a story about another environment. Some friends invited our family to their house for dinner. This was memorable in and of itself because, once you have a certain number of kids, you don’t get invited over for dinner all that often. Yet, there we were, kids in tow. After we ate, the kids went off to do whatever kids do, and we adults went into the family’s living room. At the center of the room was a circular coffee table with four plush armchairs angled in such a way that they faced each other around the coffee table. It didn’t take long to figure out what this room was designed for: conversation. Our hosts didn’t have to say anything: the space said it for them. What they valued was designed into the space.

This isn’t a point about technology or not, except in the sense of thinking about what the spaces we design incline or expect us to do. Our friends’ home was organized in such a way that the central space encouraged face-to-face conversation (other spaces inclined you to reading or playing music, etc.). The shiny new terminal at the Newark airport encouraged technologically mediated engagement — in fact, it encouraged the conditions for isolation and loneliness. In neither place did anyone have to tell you what to do or how to engage: the space itself led you down one path or another.

In his book that helps families to think about how to shape their lives and especially their living places, Andy Crouch writes about what it would mean to make our homes into places of intention. It begins, of course, with having intentions about what kind of people we hope our children might become (and thus what kind of people we, as parents, want to become). The point, then, is to make those intentions structural by building them right into how the family home is organized:

“The best way to choose character is to make it part of the furniture. Fill the center of your life together — the literal center, the heart of your home, the place where you spend the most time together — with the things that reward creativity, relationship and engagement. Push technology and cheap thrills to the edges; move deeper and more lasting things to the core. This was once natural, indeed unavoidable. Almost every home once had a hearth, the fire that gave warmth, light, heat for cooking — and entertainment too, with its dancing flames and distinctive glow. The Latin word for hearth, focus, reminds us that fire was once the center of our homes. … Homes still need a center, and the best things to put in the center of our homes are engaging things — things that require attention, reward skill, and draw us together the way the hearth once did” (“The Tech-Wise Family,” Baker Books, $16.99).

Let the space echo your voice

The question for all of us is: What do the most important spaces in our home say about what we consider most important? I could have stood in the middle of that Newark airport terminal and yelled that people should look each other in the eye until I was blue in the face (or arrested), but it wouldn’t have mattered. The space itself was inclining people in a different direction. I would have been fighting against the space, like telling people to embrace solitude in the middle of a football stadium on gameday. Rather than yelling against a space, it is more powerful to let the space itself echo your voice.

Sincerely,