From the first glimpses the world had of him from the central loggia of St. Peter’s Basilica following his election to the papacy on Aug. 26, 1978, Pope John Paul I charmed the world. He had a contagious smile, was refreshingly plainspoken, and had an attractive, authentic faith. There was great hope and optimism among many Catholics that this Smiling Pope would usher in a new springtime for the Faith. No one expected that within five weeks, he would be dead.

Pope John Paul I died only 33 days after his election to the See of Peter, and it didn’t take long for a wide array of Catholics impressed with the holiness of the September Pope to call for his canonization. This undertaking will reach a milestone and penultimate step on Sept. 4, when Pope Francis will beatify John Paul I in the same St. Peter’s Square where the former pope first captivated the hearts and imaginations of so many of the faithful.

Who was John Paul I?

Merely because he was the new man in the white papal cassock following the 15-year pontificate of Pope St. Paul VI, John Paul I brought with him to the papacy a certain mystique. And this mystique has only grown. The shock and disbelief at his sudden death gave way for conjecture and theories about what might have been, not to mention provided fodder for rumors and conspiracy theories surrounding his death — theories that the Holy See’s approach to public relations at the time of the pope’s passing did not help keep in check. In recent years, John Paul I’s cause for canonization has prompted the release of new documents and evidence that begin to set the record straight.

In a strange way, the focus on Pope John Paul I’s death has, in a sense, overshadowed his life, including his character and virtue. This has made the fullness of his story and witness at times difficult to promote, grasp and appreciate. But it appears the Holy Spirit has been working, as evidenced in the cult of devotion to him that paved the way for his beatification, and a legacy of holiness has also endured the decades.

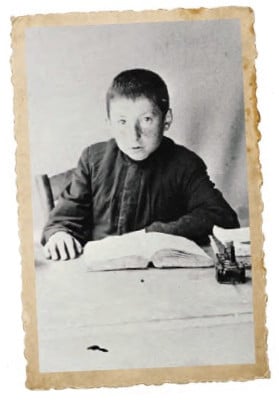

John Paul I was born Albino Luciani on Oct. 17, 1912, in a mountain village in Italy’s northern region of Veneto. Feared to be near death from the womb, he was baptized immediately by a midwife attending his birth. He was the oldest of four children. He was pugnacious and sassy as a boy, but also full of integrity and sincerity. His family was of simple means, and his father was a socialist.

Luciani was drawn to a priestly vocation from the age of 10, impressed by a Capuchin friar who preached at his parish during Lent in 1922. The following year he entered the seminary. After 12 years of preparation and study in seminaries, Luciani was ordained to the priesthood for service in the diocese of Belluno, Italy, on July 7, 1935 — having obtained a dispensation for not having yet reached the customary age of 25. After only a couple of years in parochial ministry, Father Luciani was appointed as vice rector of his former seminary, where he also taught theology, philosophy and history until 1947. During this time, Father Luciani obtained a licentiate and doctorate in theology from the Pontifical Gregorian University in Rome. While he was making a name for himself as an intellectual, he also became well-known for journalistic undertakings, particularly in regular columns in the newspaper of his diocese.

A new bishop named him diocesan chancellor in 1947, and Father Luciani was tasked with organizing a dicoesan synod. Soon after, he was named vicar general. But Father Luciani did not allow these bureaucratic roles to keep him from staying close to the people as a popular preacher and attractive catechist, especially among the youth. As diocesan director of catechetics, Father Luciani wrote the book “Catechism in Crumbs,” which laid out his approach to catechesis in a simple, relatable format so that even illiterate mountain villagers could understand.

Pope St. John XXIII, who had been cardinal archbishop of nearby Venice before his own election to the papacy, held Luciani in high regard. Less than two months after John XXIII assumed the papal throne, he appointed Luciani a bishop. He personally ordained him at St. Peter’s Basilica 12 days after the appointment, on Dec. 27, 1958.

Luciani was content in the mostly rural Diocese of Vittorio Veneto in northern Italy, where the people were industrious and pious. Like the people entrusted to his care, Luciani was a man of humility. He chose the Latin word “Humilitas” as his episcopal motto. When Luciani took up his place among his new flock, he was intent on being a teacher and servant. As bishop of Vittorio Veneto, Luciani was a participant at all sessions of the Second Vatican Council from 1962-65, and he kept the faithful of his diocese abreast of what the council accomplished and what those accomplishments would mean for the life of the Church.

Not everything was perfect for Luciani in Vittorio Veneto, a fact perhaps most keenly demonstrated by an episode with recalcitrant parishioners in the small village of Montaner. This is worth recalling given how his reaction helps understand his character, demonstrating the kind of decisive man he was, how he was willing to take unpopular positions in defense of truth, as well as his firm and uncompromising convictions. The Montaner parishioners thought they would tell Luciani who they wanted as a pastor, despite the fact that, for Catholics, pastors are assigned by the bishop since they minister on his behalf in a given parish. Luciani tried to work with the people, assigning a variety of different priests over the course of a little more than a year, but the people remained unsatisfied. To protest one priest, they built a wall in front of the main door of the parish church. Another, they locked in the rectory attic. The situation ended in schism when the faithful of that parish made it clear they were no longer in union with their bishop. In response, Luciani, accompanied by a police escort, dramatically removed the Blessed Sacrament from the parish church and assigned no further priests. As a promoter of dialogue, he was deeply concerned with the Church’s unity, making this a source of great pain.

In 1969, Pope Paul VI appointed Luciani to be patriarch of Venice, a position of significant prominence. Paul created Luciani a cardinal on March 5, 1973. Cardinal Luciani’s time in Venice was as startling and distressing as Vittorio Veneto was bucolic and serene. As a competent and gentle shepherd, Luciani was a man of the Church. He was close to the poor and working class, and he upheld Church teaching amid the liberalization of Church and society, the effects of which weighed heavily upon him. He was also attuned to evangelization through the culture, interested in literature, cinema and lending his shepherd’s voice to many periodicals. He was firm in keeping his presbyteral council from straying from his direction, insisting on adherence to liturgical norms and ensuring proper pastoral formation of priests.

Although Luciani’s name did not pop up on most Vaticanistas’ shortlists of papabile, there were a few indicators that his leadership was appreciated. A significant foreshadowing came in 1973, a few months before Luciani was named a cardinal, when Paul VI took off his stole and placed it on Luciani’s shoulders — saying, “You deserve this stole” — while making a pastoral visit to Venice. Luciani recalled the event: “he made me blush to the roots of my hair in the presence of 20,000 people … Never have I blushed so much!”

After only 26 hours into the August 1978 conclave, Luciani was elected the 262nd successor of St. Peter. The day after his election, in an Angelus address on Aug. 27, John Paul I explained what it was like:

“Yesterday morning I went to the Sistine Chapel to vote tranquilly. Never could I have imagined what was about to happen. As soon as the danger for me had begun, the two colleagues who were beside me whispered words of encouragement. One said: ‘Courage! If the Lord gives a burden, he also gives the strength to carry it.’ The other colleague said: ‘Don’t be afraid; there are so many people in the whole world who are praying for the new pope.’ When the moment of decision came, I accepted.”

It has been said that the cardinal electors at that conclave wanted to elect a pastoral man, one with the heart of a shepherd rather than experience in the bureaucratic Roman Curia. That is what made Luciani their man.

What’s in a name?

The papal election of Albino Luciani on Aug. 26, 1978, ushered in a new age for the Church. He was the first pope elected after the Second Vatican Council who had not presided over it. He was the first pope with a double name, too. Many wondered, especially in the midst of a confusing post-conciliar time, what the legacy of the council might become under the leadership of the new pope. That question was immediately resolved in the papal name Luciani chose: John Paul I.

In his own words: “I said: ‘I shall be called John Paul.’ I have neither the ‘wisdom of the heart’ of Pope John, nor the preparation and culture of Pope Paul, but I am in their place. I must seek to serve the Church. I hope that you will help me with your prayers.”

What might have been?

It is hard to say what shape John Paul I’s pontificate might have taken. We have just a few details of his short reign to provide some clues, including his own six-point plan offered in his urbi et orbi address the day after his election:

1. “To continue to put into effect the heritage of the Second Vatican Council.”

2. “To preserve the integrity of the great discipline of the Church in the life of priests and of the faithful.”

3. “To remind the entire Church that its first duty is that of evangelization.”

4. “To continue the ecumenical thrust” of his predecessors.

5. To carry on the “plan and programme for pastoral action” of Paul VI, particularly as found in his encyclical letter Ecclesiam Suam.

6. To support “all the laudable, worthy initiatives that can safeguard and increase peace in our troubled world.”

But most of what we are left with regarding John Paul I’s brief papal legacy are in his gestures and words. Commentators varied in their assessments. Secular journalists were often dismissive of him as “conservative” and “unsophisticated.” But many Church observers saw in the second of 1978’s three papacies a bit of a revolution. He dropped using the majestic “we.” He refused the tiara at his installation. He spoke simply, though he was no intellectual slouch. He appealed to ordinary men and women, although he had no ordinary life. He was open to dialogue with all. He captivated children. He spoke often of Pinocchio. He smiled. He laughed. He was authentic. He was gentle. He was joyful. He was happy.

How did he die?

Pope John Paul I’s sudden death came on the night of Sept. 28, 1978, in his bedroom in the papal apartments, most likely of a heart attack. Rumors of foul play ran wild, ranging from allegations of murder by Vatican insiders (for sweeping changes John Paul may have been preparing to make) to a plot stemming from Masonic infiltration of the Roman Curia.

After decades of speculation, new documentation has surfaced in recent years, including from the Vatican Secret Archives, on account of the investigatory phase of John Paul I’s cause for canonization. The evidence, published in English as “The September Pope” (OSV, 2021), has brought to light that the short-lived pope had been treated medically for a heart ailment and had reportedly suffered chest pain earlier in the evening before his death. He did not consult a physician. This and other documentary evidence contained in “The September Pope” — says the Holy See’s Secretary of State Cardinal Pietro Parolin in the book’s foreword — “sheds light on the epilogue to Pope Luciani’s life, finally clarifying the points that were left in limbo, amplified, and misrepresented in mystery-writer reconstructions.”

John Paul I’s funeral Mass was celebrated in a rainy St. Peter’s Square on Oct. 4, 1978, and he was buried in a new tomb in the Vatican grottoes. Although calls for his canonization came soon after his death, his cause wasn’t formally opened by his home diocese of Belluno, Italy until 2003.

From his own hand: ‘Illustrissimi’

Another aspect of John Paul I’s legacy is a collection of letters written by Luciani to various religious and historical figures, as well as fictional characters — from King David and Jesus Christ, to Pinocchio and Figaro the Barber, to Mark Twain and Charles Dickens. “Illustrissimi,” or “The Illustrious Ones,” was first published as a book in Italian in 1976 and published in English after his election to the papacy. Although it was not in print until after his death, it also provides a glimpse into Luciani’s character, faith and insight, not to mention his whimsy and imagination — all found in the following select quotations.

To Charles Dickens: “I enjoyed your [Christmas books] immensely because they are filled with love for the poor and a sense of social regeneration; they are warm with imagination and humanity…”

To St. Thérèse of Lisieux: “Thérèse, the love you bore God (and your neighbor, out of love for God) was truly worthy of Him. So our love must be: a flame that is fed on everything great and beautiful in us, that renounces everything rebellious in us; a victory that takes us on its own wings and carries us, as a gift, to the feet of God.”

To Pinocchio: “My dear Pinocchio, there are two famous remarks about the young. I commend the first, by Lacordaire, to your attention: “Have an opinion and assert it!” The second is by Clemenceau, and I do not commend it to you at all: “He has ideas, but he defends them with ardor!”

A holy man

When John Paul I died so suddenly after just 33 days as pope, the world was left wondering why. With his beatification, it seems that providence is bringing closure and clarity. Would Albino Luciani have been beatified had he stayed in Venice after the 1978 conclave that elected him pope? It’s hard to say. No more than a dozen men who held the rank of cardinal in the last 1,200 years have been inscribed in the Church’s canon of saints, while close to a third of the Church’s 266 popes have been so proclaimed. Chicago’s late Cardinal Francis E. George, O.M.I. once quipped about this disparity in 2010 when he said the few numbers of canonized cardinals either means “if you want to be a saint, don’t become a cardinal, or else that cardinals are so humble that they keep their sanctity well concealed.”

|

— Address to a group of U.S. bishops, Sept. 21, 1978 |

While complaints have been registered by both ends of the ecclesial spectrum that there are too many recent popes who have been raised to the altars, it is important to remember that individuals are beatified and canonized because they lived a life of heroic virtue, not because of the offices they held. But the office can help raise the profile of the person and attract a wider following of devotees. One can reasonably argue that is the case for John Paul I, especially when considering the fact that he was not on the shortlist of papabile for so many going into the conclave that elected him pope.

Humility was a trademark virtue of Luciani, as attested by so many who knew him and were impressed by his witness. “The Lord recommended it so much: Be humble,” he said on Sept. 6, 1978. “Even if you have done great things, say: ‘We are useless servants.’ On the contrary, the tendency in all of us is rather the opposite: to show off. Lowly, lowly: This is the Christian virtue which concerns us.”

John Paul I might have already answered the questions of the critics of his beatification in an often quoted line from before his election to the papacy: “Lived holiness is very much more widespread than officially proclaimed holiness. The pope canonizes, it’s true, only genuine saints… If we here on earth make a kind of selection, God doesn’t do so in heaven; coming into paradise, we will probably find mothers, workers, professional people, students set higher than the official saints we venerate on earth.”

The miracle

In addition to proving that John Paul I lived a life of heroic virtue, achieved in the declaration that he was worthy of veneration by the faithful in 2017, a miracle attributed to his intercession was necessary to pave the way for his beatification. An alleged miracle was rejected in 2015 by the medical commission of the Holy See’s Congregation for the Causes of Saints. The miracle, accepted by Pope Francis in 2021, involved the healing in Buenos Aires, Argentina in 2011 of an 11-year-old girl suffering from septic shock and various brain complications. Then-Cardinal Jorge Bergoglio was the city’s archbishop at the time, two years before his election as pope. A priest recommended to the girl’s mother that she entrust her daughter’s grave health condition to the intercession of the late pope. And when she did, also joined in prayer by medical staff at the hospital, things changed within hours.

Michael R. Heinlein is editor of OSV’s Simply Catholic. He writes from Indiana.

“What a wonderful thing it is when families realize the power they have for the sanctification of husband and wife and the reciprocal influence between parents and children.”

“What a wonderful thing it is when families realize the power they have for the sanctification of husband and wife and the reciprocal influence between parents and children.”