Acknowledgment that the United States is in a severe demographic crisis has been surfacing lately and in some unlikely places. During an hour-long speech on the Senate floor, Republican Sen. J.D. Vance of Ohio argued against a bill that would provide a funding package for Ukraine, saying, “At the same time that world leaders play armchair general with the Ukraine conflict, their own societies are decaying. Not a single country, not a single country, even the United States, within the NATO alliance has birthrates at replacement level. We don’t have enough families and children to continue as a nation, and yet we’re talking about problems 6,000 miles away.”

Sen. Vance isn’t the only one to have raised the issue. Diaper manufacturers are sounding the alarm. These businesses, including Kimberly-Clark Corp., which makes Huggies, and Proctor & Gamble Co., which makes Pampers and Luvs, are facing threats in an industry that has been stable since the invention of disposable diapers during World War II.

Even immigrant groups, which have long provided population stability in the United States, have seen a decrease in birth rates. According to the U.S. Census Bureau, the fertility rate of foreign-born Hispanic women has declined overall since 1990 despite a “mini baby boom” in the early 2000s.

Birth rates saw a noticeable decline during the COVID-19 pandemic. In 2021, there was a baby bust on the order of 100,000 births, according to the Brookings Institute. As COVID waned, there was an initial slight recovery. But births had steadily declined for many years before the pandemic. There was a 13% reduction in births from 2007 to 2019, amounting to more than 600,000 fewer births.

Having kids is now ‘optional’

Why is this trend happening? Many have pointed to the rising cost of raising a child to the age of 17, which is now estimated at more than $310,605. Yet that price tag, in part, includes a set of expectations and priorities that are culturally chosen. One couple recently profiled by the Los Angeles Times explained their decision not to have children despite having a combined annual income of $200,000. Of course, there are real economic challenges to families, child care costs and the growing difficulty of affording a house among them. Yet families making far less who decide to have children because of the inherent, inestimable worth of every life often find ways of making ends meet.

Making sacrifices in order to have large families has, until relatively recently, been considered a duty and a joy, the most common way in which a married couple serves the greater good of society.

A 2021 Pew survey reveals that a majority of childless adults have not had children because “they just don’t want to have kids.” The implication is that contributing to the common good by raising future generations is no longer a duty or even a convention but merely an option.

Falling birth rates are an economic problem. They are a societal problem. And they are a religious problem. To address the impending demographic crisis, then, we need to take a three-pronged approach.

Making church and society family friendly

First, we should create economic incentives that make it possible for families to raise children. This begins by removing financial obstacles, particularly for younger newlywed couples. A particular concern for parents is child care. We need to offer affordable, healthy child care options for parents, including subsidizing the household income of families who decide to have one parent stay home with his or her children.

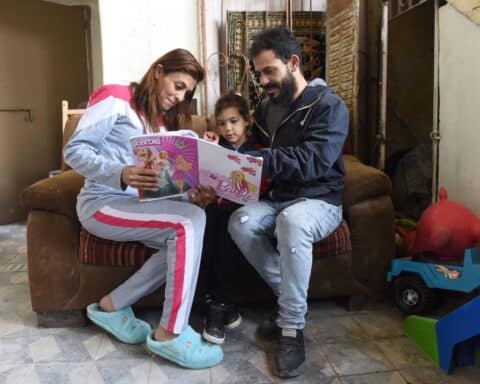

Second, we should be attentive to the ways we make our society more broadly family-friendly. Are children welcome at our public events and in our public spaces? Not only do public spaces need to support parents and family life, but workplaces do, too. Do companies offer the flexibility and assistance that young parents need for their vocation as parents? And before families are formed, are our colleges and universities educating students with the understanding that many — most, if we are to have a healthy society — will become parents and not merely wage-earners? Are we portraying that vocation in an attractive light?

Finally, as Catholics, what do we do to encourage and support family life in our parishes? Is child care offered in conjunction with parish events? Is there a network of parish babysitters and volunteers who are able to assist families? Are children welcomed or scorned at Sunday Mass? And do we hear, from the pulpit, anything about the Church’s long tradition of advocating for a sustainable family wage?

Sacrifices

Making sacrifices to have large families has, until relatively recently, been considered a duty and a joy, the most common way in which a married couple serves the greater good of society. Most of us will not write the great American novel or invent a cure for cancer, but we will give birth to, provide for and raise children. Even those who are not parents themselves traditionally have taken concrete responsibility for the formation of future generations.

Has our materialistic society, with its ever-multiplying distractions, simply made being a parent too basic, too menial, too boring? Mass-produced and mass-prescribed birth control — which has become so prevalent as to have an environmental impact — is the technological tool that enables many to act on this cultural assumption. As we face the prospect of a future in which there aren’t enough people to keep not only our economy but our physical infrastructure running, we may pay a steep price for our lifestyle choices. We must take steps to mitigate this multifaceted crisis now.