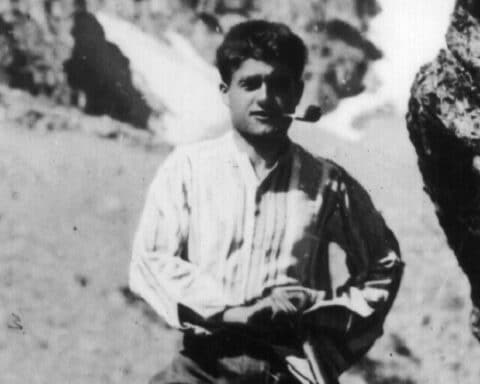

“I was a 26-year-old priest with nothing but God’s grace and good humor.” Years later, St. Josemaria Escriva liked to make that point when explaining how things had stood with him in 1928 when he “saw” Opus Dei and realized that founding this work of God was his special assignment in the divine plan.

Opus Dei today is a vigorous worldwide organization with some 95,000 members, but it was very far from that at the start. “The Work was born very small,” Msgr. Escriva recalled. “It was only a young priest’s desire to do what was asked of him.”

While it’s often described as conservative, Opus Dei has pioneered in spreading the idea that lay people are called to achieve sanctity in and through their ordinary activities in secular settings — job, family life, recreation and the rest. In promoting this message, the work and its founder anticipated the universal call to holiness that the Second Vatican Council proclaimed in its Constitution on the Church: “All Christians in any state or walk of life are called to the fullness of Christian life and to the perfection of love” (Lumen Gentium, No. 40).

Beginnings

But that is now. Starting out, though, there was nothing to suggest the role Josemaria Escriva would have in God’s plans and certainly no reason to suppose that a bold new vision of the Catholic laity would be central to it.

Born in Barbastro, a small town in northern Spain, on Jan. 9, 1902, he contracted a virulent infection when he was 2 and was expected to die. His parents promised to make a pilgrimage to a Marian shrine if he recovered. The little boy lived, the pilgrimage was made, and today, the shrine at Torreciudad is the site of a major Opus Dei center.

In 1918, having already begun to receive intimations that God wanted something special of him that would require him to be a priest, he entered the seminary. Domine, ut sit, “Lord, that I may see,” he prayed, repeating the prayer of a blind man whose sight Jesus had restored (cf. Lk 18:41). Ordained in 1925, he did two years of parish work, then went to Madrid to study for a doctorate in law at the University of Madrid. When not studying, he busied himself visiting the poor in the city’s slums and charity hospitals.

Read more from our Turning Points series here.

In late September of the following year, he joined other priests on retreat at the Vincentian Fathers’ headquarters. With him, he brought the notes he’d jotted of what he took to be divinely inspired hints concerning the special work God wanted him to do. Then, on the morning of Tuesday, Oct. 2, 1928, the feast of the Guardian Angels, something remarkable happened. Later, he describes it like this: “I received an illumination about the entire Work, while I was reading those papers. Deeply moved, I knelt down — I was alone in my room, at a time between one talk and the next — and gave thanks to our Lord, and I remember with a heart full of emotion the ringing of the bells of the [nearby] Church of Our Lady of the Angels.”

Clear as it was, though, this turning point left many important matters unspecified. At the beginning, the youthful founder believed that membership in this new group should be confined to men, and it took another illumination, on February 14, 1930, before he understood that Opus Dei was for women, too.

Gradually he began to attract members to the work — university students and young professionals — but expansion was halted in 1936 by the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War.

With his life in danger from leftist militias, the priest hid for months in Madrid, then, with several companions, made his way north to Burgos where he lived for the rest of the war while ministering to young men in the Nationalist army.

The civil war was barely over before World War II erupted, further delaying Opus Dei’s international spread. But in 1946, the founder moved the headquarters to Rome, and now the work began to grow rapidly in Europe and beyond — North America, Latin America, Africa, Asia and the Far East. In the United States, it began in Chicago in the winter of 1949.

Opus Dei

By this point, the story of Msgr. Escriva’s life had largely become the story of Opus Dei’s development. But its purpose has remained the same as it was at the start. Msgr. Escriva once put it this way: “Opus Dei aims to encourage people of every sector of society to desire holiness in the midst of the world. In other words, it proposes to help ordinary citizens lead a fully Christian life, without modifying their normal way of life, their aspirations and ambitions. … They do not join Opus Dei to give up their job. … What they look for in the Work is the spiritual help they need to sanctify their ordinary work.”

The program of members includes daily Mass and Communion, weekly confession, daily mental prayer and recitation of the Rosary, participation in a yearly retreat and monthly days of recollection, regular reading of the New Testament and other spiritual reading, and some form of apostolic activity.

Far and away, the largest number of members are lay people, most of them married with children. A smaller group, the “numeraries,” are celibate and live with other numeraries in Opus Dei centers. There are about 2,000 priest members, along with another 2,000 or so diocesan priests affiliated with the group for spiritual support and encouragement, and a large number of “cooperators,” some non-Catholics, who support its work.

While the group deliberately keeps its institutional presence to a minimum so as to avoid getting bogged down in institutional upkeep, it does have a few institutions, including international centers of formation in Rome for men and women members, universities in several countries, secondary schools and some other training institutions. Currently, it is present in more than 90 countries.

Msgr. Escriva authored several books, including homily collections and other works. Best known is “The Way,” a small volume for use in prayer composed of 999 aphorisms and anecdotes, many drawn from life. To date, it has sold 4 million copies in 43 languages.

The Second Vatican Council, in its decree on priests (Presbyterorum Ordinis, No. 10), provided for new bodies called personal prelatures to serve the pastoral needs of particular persons. In 1982, Pope St. John Paul II made Opus Dei the first, and so far only, personal prelature.

In 2022, following a reorganization of the Roman Curia, Pope Francis decreed that the work should no longer report to the curial office for bishops but to the office for priests. He also specified that, in keeping with Opus Dei’s founding charism, its prelate not be a bishop as Msgr. Escriva’s first two successors had been. The current prelate, Msgr. Fernando Ocariz, welcomed the changes as “an opportunity to go more deeply into the spirit that Our Lord instilled in our founder.”

Humility

And what exactly was that spirit? Perhaps the answer can be seen in something St. Josemaria — a founder and innovator of note — said about the virtue of humility: “Humility means looking at ourselves as we really are, honestly and without excuses. And when we realize that we are worth hardly anything, we can then open ourselves to God’s greatness: it is there our greatness lies.”

He died in Rome of cardiac arrest on June 26, 1975, and was canonized in 2002 by Pope John Paul II, who called him “among the great witnesses of Christianity.” Seventy-four years earlier, the young priest who had only “God’s grace and good humor” would probably have been amazed at hearing that.