The Gospel of Matthew tells us: “[About] three o’clock Jesus cried out in a loud voice, ‘Eli, Eli, lema sabachthani?‘ which means, ‘My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?'” (Mt 27:46). This saying of the Lord raises the question of how the Lord inwardly related to the Father amid suffering. By implication, it raises the question of how you and I should relate to God amid our sufferings too. What is the Christlike way to suffer?

“[About] three o’clock Jesus cried out in a loud voice, ‘Eli, Eli, lema sabachthani?‘ which means, ‘My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?'” (Mt 27:46)

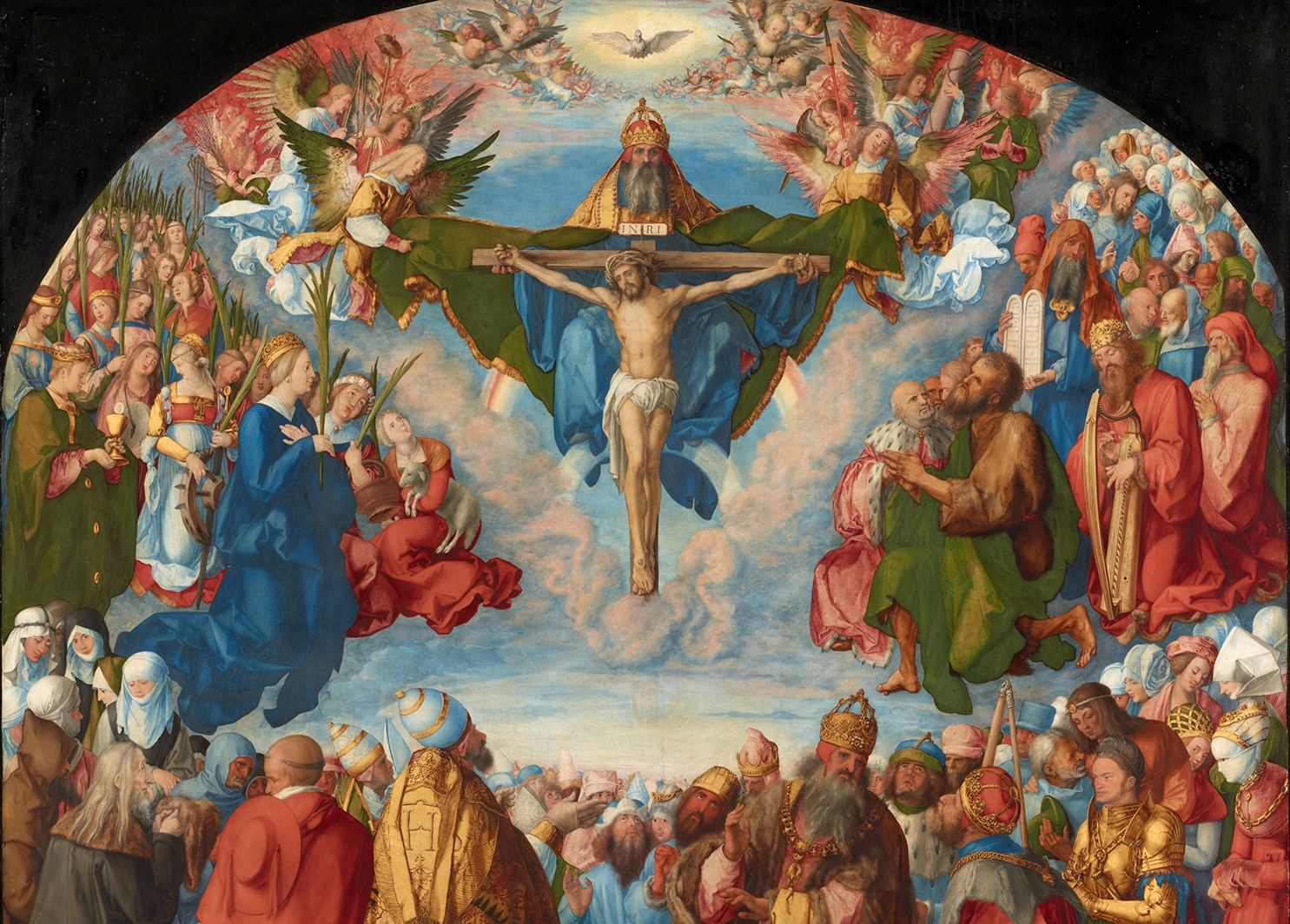

The Fourth Last Word

Pope St. John Paul II once said that one of the distinguishing characteristics of human suffering, as distinct from the suffering of animals, is that human beings question their suffering (cf. Salvifici Dolores, No. 9). When we suffer, we ask God why we suffer. It is natural for us to ask the question of God because human beings naturally know God exists and naturally expect God to order the world well. Suffering seems to fly in the face of our natural understanding of the God who is all wisdom and love.

To ask God for the why of our suffering is not sinful in itself. To ask is not necessarily a sign of protest, doubt or mistrust in God. It can be an honest question. Honesty and vulnerability before God are always appropriate. To open our hearts and minds to God, and to share with him our actual thoughts, questions, and afflictions is a good thing. It can even be the doorway to a deeper relationship with God — especially amid suffering.

Interpreted in Scripture

The Lord Jesus was fully human. He was like us in all things but sin. He suffered immensely on the cross, and he suffered in a human way. Therefore, he asked why. He raised the question to the Father. Would he have been fully human if amid such great suffering, he had not asked why? By asking the question, Christ was “leaving you an example” (1 Pt 2:21). He revealed to us how right it is to ask God honestly why we suffer. His question was no rebellion or protest, but a certain turn of events in his prayer from the cross.

Jesus was in prayer, not only at the moment he expired but throughout his whole passion, beginning in the Garden of Gethsemane. Experience tells us that there are twists and turns in our prayer. Our prayer changes from one moment to the next. So, too, in the prayer of Christ. In the garden, he prayed to the Father to take away the cup of suffering, if possible, but “your will be done” (Mt 26:42). In a later moment, he prays for his persecutors to be forgiven (cf. Lk 23:34). Yet now, in another moment, he honestly acknowledges before God the full measure of affliction that is upon him. To do so, he draws from Israel’s treasure chest of prayer — the Psalms.

“My God, my God, why have you abandoned me?” is the first line of Psalm 22. The Lord did not simply recite the line, but cried out the words. In so doing, he left us another example. Honest prayer is wholehearted. It engages the whole human being body and soul. When prayer rises up from the depths of the soul, it often comes out through the body in a loud voice. “Out of the depths I call to you, LORD; Lord, hear my voice” (Ps 130:1).

When the Lord cried out the first line of Psalm 22, he did so not only in prayer to the Father but also in proclamation to the people surrounding him. In the ancient world, Scripture was not yet divided numerically into chapters and verses.

The psalms were known and remembered, rather, according to their first line. By crying out the first line of Psalm 22, the Lord was calling everyone’s attention to that psalm to demonstrate how it was being fulfilled in their midst. Psalm 22, in fact, is an eerily accurate prediction of how Christ was now suffering: “scorned by men and despised by the people, all who see me mock at me” (Ps 22:7-8). Verses 8-9 says, “[They] shake their heads at me: ‘He relied on the LORD — let him deliver him.'” Verses 15 and 16 describe his actual physical sufferings: “all my bones are disjointed … my tongue cleaves to my palate.” Most accurately of all, verse 19 predicts how “they divide my garments among them, for my clothing they cast lots.” When Jesus cried out the first line of Psalm 22, he offered a sort of divine commentary on what was taking place. He interpreted everything in light of the Word of God. Only when we read our lives in light of the word of God do we really understand the divine truth of things hidden in plain sight.

Yet, we might still ask: what was the measure of suffering that moved our Lord to pray “my God, my God, why have you abandoned me?” The full measure of his suffering is a mystery, but not simply unintelligible.

The outer and inner heart

Following St. Paul, Catholic anthropology distinguishes between the “outer self” and the “inner self” (2 Cor 4:16). The outer man is a certain place within us, but not the deepest place. It is the place of sensations, images, and passions — the place where physical and psychological experience flow. The inner man is a deeper place within each of us — the place of a higher and more enduring knowledge and love. More importantly, it is the place of one’s personal knowledge and love of God.

The inner self might also be called the deep heart, and the outer self might also be called the area around the heart. The deep heart has spiritual eyes all of its own — the eyes of the heart (cf. Eph 1:18). When the eyes of our hearts are illuminated by the light of grace, we know God in the depths of our hearts in a most inward, personal and familiar way. What is more, such knowledge of God in the depths of our hearts can endure through the most horrible of experiences, taking place in the area around our hearts.

Cruelest of torments

Since the Lord Jesus was fully human, he too had in himself an inner man and an outer man — his deep heart and the area around his heart. During his passion, Jesus was subjected to the cruelest of torments. He endured the blows of fists and scourges, the punctures of thorns and nails, the loss of blood and the deepest thirst. His disciple had betrayed him. His rivals had captured him. His friends had fled. His mother wept. There is no tongue on earth able to tell the full measure of affliction that pierced the body and psyche of Jesus Christ. The area around his heart was overwhelmed.

Pope St. John Paul II tells us that in the outer man, in the area around his heart, Jesus “was reduced to a wasteland. He no longer felt the presence of the Father, but he underwent the tragic experience of the most complete desolation” (General Audience, Nov. 30, 1988).

When Jesus cried out his prayer from the cross, he was honestly acknowledging everything that was taking place in the area around his heart. Yet, the area around the heart is not the deepest thing within a human being, and it was not the deepest thing within Jesus Christ. “Man has a deep heart,” it says in the Psalms (Ps 64:6 LXX, Douay-Rheims). So, too, did Jesus Christ. In his deep heart, Jesus Christ always remained in union with the Father. The light of the Father illuminated the eyes of his heart in a special way, and the heart of Jesus always remained a burning furnace of love for the Father. Throughout the course of his passion, the knowledge and love of the Father sustained Our Lord in the depths of his heart.

For this reason, Pope John Paul II also says: “if Jesus felt abandoned by the Father, he knew however that that was not really so. … Jesus had the clear vision of God and the certainty of his union with the Father dominant in his mind” (General Audience, Nov. 30, 1988).

Jesus suffered so much on the cross that a sense of abandonment by God knocked on the door of his deep heart, but in his deep heart, Jesus did not consent. He remained true to the Father of lights. For the Father did not hide his face from the eyes of our Lord’s heart. As Psalm 22:25 says, “[He] did not turn away from me, but has heard when he cried to him.” Just as the psalm was being fulfilled in outwardly observable events, so too it was being fulfilled in the inward and invisible depths of the heart of Jesus.

The light of grace shines in our hearts too. It is called the light of faith. Amid suffering, we might go through a thousand emotions. We might well feel terrified or abandoned. It is proper to voice our sense of abandonment and our fears to God. In reality, however, God never abandons us. The key is to remember one thing. “I am with you always, until the end of the age” (Mt 28:20).