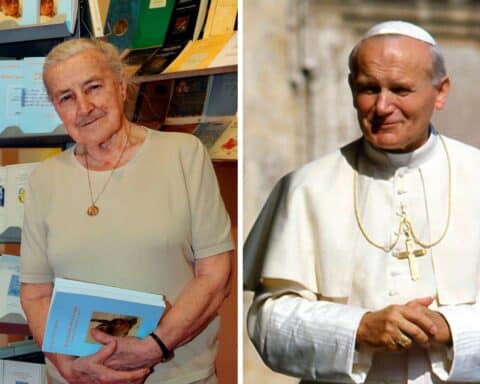

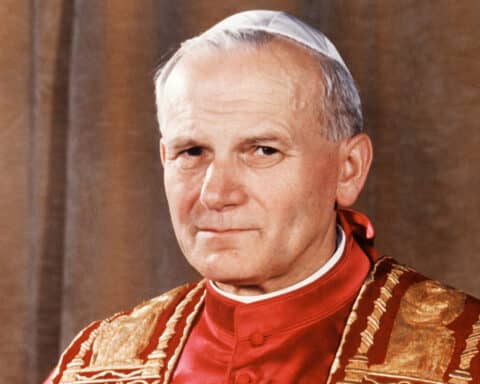

Pope St. John Paul II promulgated Veritatis Splendor (“The Splendor of the Truth”) on Aug. 6, 1993 — 30 years ago. I find these words hard to believe even as I write them, since this encyclical, far from losing relevance with age, seems only to grow in its importance.

It was written amidst a great deal of turmoil regarding the moral teachings of the Church and, in its upholding of traditional doctrines and, perhaps more importantly, its shedding further light thereon, it provided guidance and direction for the moral theologians who, like me, came of age in its wake. I have no doubt that it will, like Rerum Novarum, be included among those encyclicals that so profoundly influenced Catholic thought that it will be impossible to understand Catholic moral theology without having read it. It will be essential reading, furthermore, not only for those who want to understand contemporary moral theology but for those who want to avoid the mistakes of the past.

These mistakes emerged in the flurry of theological activity that followed the Second Vatican Council, which closed in 1965 and led the various sub-disciplines of Catholic theology to reevaluate their approaches to understanding the truths of revelation. This reevaluation was not all bad — far from it — and it bore much fruit that has since remained with the Church. In the field of moral theology, for example, this era witnessed a recovery of the understanding that moral theology is ultimately about happiness, not rules. The reason why we follow rules is that we want to be happy, not because a ruler-toting sister told us to. But some of the theological exuberance of this time period led many to accept ideas that were at odds with the perennial teachings of the Church. Veritatis Splendor was written, in part, to combat two of them: fundamental option theory and proportionalism.

Fundamental option theory

Fundamental option theory is based on the idea that every person has a basic commitment or trajectory — that is, he or she has opted in a fundamental way to God or to something else. This, as far as it goes, is true, and Pope John Paul II says as much. The problem emerges when proponents of fundamental option theory try to distinguish the fundamental option from concrete actions. Think, for example, of a person who says, “Well, I am not the best Catholic; I don’t go to church every Sunday, but I am basically a good person.” This is a colloquial expression of the idea behind fundamental option theory: A person can be, fundamentally, good or bad, regardless of the particular actions that they perform, since they have decided, deep down, that they love God — even if they do not do everything, as Catholics, or as human beings following the natural law, they are supposed to.

John Paul II argues that this idea is not only contrary to Church teaching, but it also does not make sense on a rational level. Regarding Church teaching: If fundamental option theory were true, then it would destroy the notion of mortal sin, which, in one single act, removes a person from the state of grace and destroys the charity that was in their heart. And this, of course, is not just a matter of doctrine — it also makes sense. When we act, we act in accord with our beliefs and commitments, such that our actions sometimes reveal that we believe or are committed to something other than what we say we are. A man, for example, who cheats on his wife, is showing with his actions that he does not love her as much as he says he does. Likewise, it is impossible to say that one is a good Catholic while casually ignoring the moral teachings of the Church.

Proportionalism

Proportionalism was a school of thought that called the traditional category of “intrinsic evil” into question. It is no secret that Catholics like rules. Not only do we have a lot of them, we have different kinds of them. Some admit of exceptions — for example, you must go to church on Sunday, unless you are sick. Other rules do not admit exceptions: You must never commit adultery, no matter how noble your intentions. Intrinsically evil actions fall into this second category. This term describes actions that are evil in themselves — that is, evil because of the kind of action that they are. Such actions, which never admit of exceptions, include things such as murder, fornication and blasphemy.

It is not hard to recognize or define such actions; everyone knows what murder is, and proof of this is that juries do not need a lesson in ethics before they are asked to judge whether a defendant is guilty of murder or not. The proportionalists, however, tried to develop a novel methodology for defining actions in terms of intention. If, according to Catholic teaching, a person can ward off an attack, even if lethal force is required, as long as he intends to defend himself and not to kill the attacker, then why, the proportionalsts wonder, can we not say that one person could justly kill another if he had a very good reason (say, to stop a war)? Why would such an action have to be called “murder” and not “preventing a war”? John Paul II points out that labeling actions in such a way — in terms of what an agent intends to accomplish by them, and not in terms of what they are in themselves — leads to a position where any action could conceivably be justified somehow, which means that nothing would be absolutely forbidden. If Christians thought this historically, then there would never have been any martyrs, since anyone faced with a difficult choice could always rationalize doing something evil for the sake of something good.

Understanding the moral life

With simple and straightforward arguments such as these, John Paul II did much in Veritatis Splendor to get Catholic moral theology back on track by correcting these two widespread errors. But more than this, and what is perhaps the real legacy of Veritatis Splendor, John Paul II also explained why it is so important to uphold the teaching that certain kinds of behavior are absolutely forbidden.

The Christian life is a life lived in love and in imitation of Jesus Christ and of the love that he showed for the Church. Just as there are certain actions — such as adultery — that are incompatible with the marital love shared between a husband and wife, so there are certain actions — such as blasphemy — that are incompatible with the love that God has poured into our hearts. In short, behind every “no,” there is a much greater “yes.” If Christians are called not to kill, it is not just because killing is bad, but more fundamentally because life is good. If Christians are called not to fornicate, it is because the good of conjugal love is too great to transgress. This is the legacy of Veritatis Splendor. If the moral life is one lived in love, then its rules seem less like burdens placed upon one’s shoulders and more like guideposts that illuminate the boundaries of the straight and narrow path of holiness.