This year we are celebrating the 60th anniversary of the opening of the Second Vatican Council (1962-65). The question of the council’s legacy is an ongoing matter of continuing debate among theologians whose discussions of the finer theological points of the council leave most average Catholics yawning. The relationship between nature and grace? What is that? Neo-scholasticism versus more modern theologies? Hmmm … don’t really understand theology anyway, so who cares? Religious freedom for all in civil society? Duh, isn’t that a no-brainer? Non-Catholics have a legit shot at salvation? Well, of course they do. Mass in the vernacular in a reformed liturgy? Is that still a question for anyone other than a small group of right-wing Latin fanatics over at that abandoned parish downtown? Local bishops now have more independent authority from the pope than they did before? Really? Seems the pope is still the celebrity center of attention with the Catholic media reporting on the pope’s every hiccup and facial twitch.

Oct. 7, 1962, issue of Our Sunday Visitor (bottom)

Thus, the deeper question, beyond all of the ongoing theological debates, is why an average Catholic in the pews should continue to care about the council at all since it seems now to be in our rearview mirrors as “your grandfather’s council,” lacking any real existential grip on the day-to-day concerns of average people. The cultural thought-world of the early ’60s seems so foreign to us now, with the concerns of that distant time now residing as a mere caricature in our minds lumped together with vague memories of hippies, drugs, Vietnam and the Beatles. And so we can perhaps be excused for a certain indifference to the whole affair. After all, aren’t there even perfectly orthodox theologians who are now saying that the council’s moment has passed and we need a Vatican III to set things right and to take up more contemporary concerns? Aren’t there disgruntled traditional Catholics out there who blame the council for all of the Church’s modern woes and that we should now just ignore it as a failure? And aren’t there a bunch of liberal Catholics in the Church today in increasing numbers who say that we should just move on from the council and embrace the modern world’s progressive agenda, especially in matters of morality?

All of these observations are true, and to the extent that the average Catholic is aware of such things — no matter how vaguely — there is an understandable intellectual and spiritual exhaustion concerning the council that can only breed a certain frustration that we are fixated on a now distantly past ecclesial event to the detriment of addressing the real needs of today. Should we not instead be focused on why there are so few religious vocations, why our children are walking away from the Faith in droves, why so many parishes and schools are closing, and why we still can’t seem to come to grips with the fall-out from the sex abuse crisis? Is not a concern over the council directly analogous to Nero fiddling as Rome burned around him? Most Catholics today, I think, would answer that last question in the affirmative, even as they continue to question the credibility of their shepherds who seem more focused today on financial and managerial concerns rather than on the more fundamental question of why anyone should continue to believe at all.

A new claim

Nevertheless, and despite the heartfelt legitimacy of all of these issues, my claim is exactly the opposite. In my view, the council has been a victim here of its own success. Yes, you heard that right. The council was, and contrary to the reigning narrative, a success and not a failure. There is a sad tendency these days to focus on all of the turmoil that happened in the wake of the council and to use that turmoil as the primary metric for assessing the success of the conciliar project. But I think this is a deeply problematic way of assessing the council and is flawed on multiple levels.

First, if you know even a little Church history, then you are undoubtedly aware that many of the Church’s most important and consequential councils created enormous controversy and turmoil in their wake. Just think of the very first ecumenical council of the Church, the council of Nicaea (A.D. 325), which was called by the freshly minted Christian, Emperor Constantine, in order to combat the groundswell of support for what is now known as the Arian heresy. “Arianism” (named after the priest Arius) was, in a nutshell, the theological assertion that Christ was not co-equal to the Father in divinity but was instead a “creature” like other creatures, albeit the highest creature in the hierarchy of God’s creation. It was a powerful and popular heresy since it fit so well into the then-reigning platonic cosmological/philosophical paradigm. In other words, it was a theology perfectly tailored to reflect the “spirit” of the times, which accounts for its wild popularity among the clergy in particular. But Nicaea condemned this theology and affirmed that Christ was “consubstantial” with the Father, which was just a fancy metaphysical term meant to affirm that Christ was equal in divinity to the Father. It then issued the famous Nicene Creed that we still recite at every Sunday Mass and high holy days some 1700 years later.

So, case settled, right? Wrong. There were still influential bishops and Roman authorities who refused to accept the conciliar definitions, and the great debate raged on for many more decades and was not really completely resolved for another century or more. And think of poor St. Athanasius, a tireless champion of Nicene orthodoxy, who faced relentless persecution and exile for his steadfast support of the full divinity of Christ. And it took several more ecumenical councils over several more centuries to completely flesh out the full significance of the Nicene affirmations, which required the development of whole new theological and philosophical categories that were also controversial in their own right, setting off raging debates that continued on for centuries and that even led some churches to break away into schism over what they believed were the “novelties” of the preceding councils. St. Maximus the Confessor (c. A.D. 580-662), centuries after Nicaea, was persecuted for his defense of the various conciliar affirmations concerning Christ, and was put on trial for heresy in Constantinople, which eventually led to his tongue being cut out and his right hand (his writing hand) being cut-off so that he would cease his activities of preaching and writing. He died shortly thereafter.

Compared to such turmoil and persecutions, the conciliar mayhem after Vatican II looks positively pale and tame in comparison. It is, therefore, laughable from a strictly historical perspective that a mere 60 years of controversy and debate should be used as an argument against the “success” of Vatican II. Furthermore, we see that the post conciliar chaos was caused by the exact same social forces that caused the problems after Nicaea — namely, that there were many in the Church who wanted the Church to conform to the cultural and moral norms of the current culture as well as the philosophical ideologies that animated that culture. It is a story as old as the Church herself, as we see in the letters of St. Paul as he struggled to get his congregations to stop thinking like Roman pagans and trying to fit Christ into that matrix.

What average Catholics need

My point in all of this is to point out that even if we feel a certain exhaustion over the council, we must not allow ourselves to become so jaded to the controversies that we just throw up our hands and throw in the towel. Like it or not, Vatican II was the most important Catholic event of modern times, and despite the disagreements over its meaning — and despite our fatigue over those disagreements — we must not allow ourselves to succumb to the temptation of a weariness that causes our devotion to its message to wane. What if Athanasius or Maximus had thought this way? Had they given up the cause, the Church would have suffered even greater indignities and distortions that would have taken several more centuries than it already did to sort out. Likewise for us, since if we were to just give up on the council now, we would be turning the Church over to those very forces that distorted its message in the first place, which would set us back even further.

The “average Catholic,” of course, does not think in these kinds of categories, and it therefore falls upon our shepherds to be more diligent in explaining it all to us, so that the average Catholic can, indeed, come to appreciate what is at stake in these debates. Because what may appear to the regular Catholic in the pews as nothing more than an arcane theological exercise in hair splitting is, in fact, something of tremendous importance — as important in its own way as the theological hair splitting at Nicaea, which, though far removed from the ordinary discourse of ordinary Christians, was of world-changing significance that altered forever the course of history, both secular and sacred. Theology might be dull to most, and it might seem a nerdy form of discourse among pin-headed, geeky intellectuals, but it is of central importance to the Church, and the laity must, therefore, be taught theology by her shepherds in a way that theological language is transformed into the language of evangelical witness.

It can be done and has been done, and so the rejoinder that this is impossible is demonstrably false. Just look at the success of Bishop Robert Barron’s Word on Fire materials that are extremely popular among rank-and-file Catholics. This also goes to show that there is an opposite error very prevalent among many theologians and shepherds who assume that the laity cannot handle such things and then infantilize the laity with boring and anodyne homilies filled with “stories” and jokes and never rise to the level of a serious challenge or intellectual provocation. Because the fact is, there are millions and millions of educated modern Catholics who are exposed to this boring form of Catholicism and who then compare it to their educated and sophisticated knowledge of any number of topics, and they find that the Faith by comparison seems childish and utterly superficial. And this is true as well for very young Catholics who can handle far more theological sophistication than we give them credit for and who are actually starved for a Church that is deeper and more profound, and, therefore, more interesting. I cannot tell you how many times when I was still a professor of theology that I would finish a class and have droves of students say to me, “Why is this the first time I am hearing this? Why has this never been taught to me? This is wonderful!”

And all of this has a direct bearing on the ongoing significance of the council and why average Catholics should still care about it.

Successes of the council

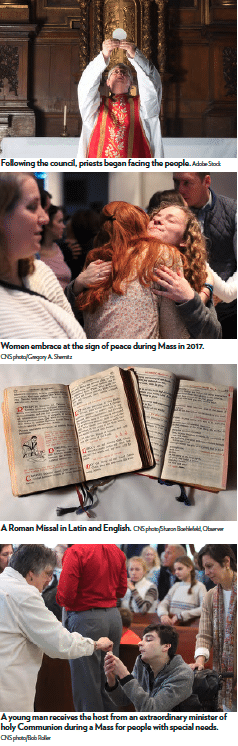

There is also the fact that Mass is now in the vernacular language of the people, which I think is a very good thing. And even if the modern liturgy could use some reforming, the fact remains that it was because of the council that we can all now pray the liturgy in our mother tongues instead of sitting back, as so many did before the council, and let the priest do his thing while we prayed a Rosary. It is also a good thing that Catholics, because of the council, are able to embrace the concept of religious freedom and to, therefore, view evangelization as a noncoercive enterprise of proposing the Gospel that is also the responsibility of us all and not just something for missionaries in some far off land.

In other words, we must not allow the successes of the council to seem like “obvious things that would have happened anyway” and, because that is not true, further realize that there is still much work to be done and still a great danger that those successes will be lost by our own inaction and indifference to what is still at stake. Because, make no mistake, there are forces at work in the Church today — both on the right and the left — that want nothing more than to destroy those conciliar successes. Therefore, if we adopt an insouciant attitude of indifference we may wake up someday soon to a Church we do not recognize. And then we will all wonder, “what happened?” and scratch our heads in disbelief over the sad state of affairs that has come upon us.

Universal call to holiness

But there is one aspect of the council, central to its message and mission, that remains woefully underdeveloped and is one of the primary causes of many of the post-conciliar pastoral failures. And that is the council’s emphasis on the universal call to holiness as an absolutely essential aspect of what the Church must be in the modern world. And this is also the primary reason why average Catholics who do care deeply for the Faith should still view the council as an event of a deep and ongoing significance. The council was a missionary council, as Pope St. Paul VI and every pope since has emphasized. The council made many noteworthy advances in theology and doctrine, but it was all done with an eye toward rejuvenating the Church’s evangelizing efforts in the modern world. The council fathers understood that the often legalistic and superficial “contractual Catholicism” of the Church of that time had led to an infantilized laity who tended to view the whole enterprise as an effort in “following the rules” established by the hierarchy. And the council further understood, given the democratic nature of modern society and the diminution of respect for authority and hierarchy — especially religious authority and hierarchy — that going forward, evangelization could no longer be confined to the ranks of the clergy and that the laity needed to be energized and empowered to take the Gospel into the world and to leaven that world with its message.

However, there is an old Latin phrase: Nemo dat quod non habet. This means, “you cannot give away what you do not rightfully possess.” Therefore, in order for the laity to be able to “give away” the Gospel message, they themselves had to live it with more evangelical fervor and, indeed, with a certain radicality in order to “rightfully possess” the very thing they need to share. Sadly, instead of this message of a universal call to holiness, what we got instead in the popular Catholicism, put forward in the media and by many priests and bishops in the post-conciliar era, was a message of accommodation to the values of the modern world. The conciliar call to “open the windows of the Church” and to go out into the world with the Gospel morphed instead into a Church that allowed the culture to blow in like a hurricane. The message that you can find holiness even in doing ordinary things was then transformed into its opposite: namely, that it is holy to be ordinary. After that happened, the rout was on and the bottom fell out of this most central of conciliar ambitions. We can debate forever why this happened, and that is an important debate to have, but one thing is certain: The council as such was not the cause of the debacle but its victim. And I make that claim with full knowledge of those who think the opposite.

Therefore, even if the average Catholic may not know it, the council remains significant insofar as its gains and successes need to be solidified, and that means the laity need to take up the unfinished conciliar business of seriously seeking the path of holiness. And I will further add that this is no longer an option for us but, rather, a necessity. Cultural Catholicism is dead. And the forces within modern culture are all lined up against the message of the Gospel. Therefore, a lukewarm, half-way house Catholicism that merely drifts with that culture will not hold as all of the current statistics about Church affiliation bear out. For every new Catholic entering the Church, there are seven who leave. It should be quite clear, therefore, that only an intentional Catholicism, fully embraced and seriously lived out, will survive.

C.S. Lewis once compared modern Christians to eggs and said that, like an egg, we must either hatch or go bad. Choosing to stand where we are without transformation is no longer an option. Therefore, the ongoing significance of Vatican II is clear. It is the time for the laity to hatch and to spark a revolution of the heart at the center of the Church.

Larry Chapp writes from Pennsylvania.

| Major documents of the council |

|---|

|

The council published 16 documents in total: four constitutions (in bold), three declarations and nine decrees.

|