It is reported that, with his final breath, Pope Emeritus Benedict XVI murmured, “Lord, I love you.” It was a last statement of faith and of devotion uninterrupted during a long life, and it was a declaration of gratitude.

Author George Weigel, who often wrote about Pope Benedict, said that Josef Ratzinger regarded the Gospel of Christ to be the light of the world, and he yearned to share the Gospel with the world.

Joseph Ratzinger, known to history as Pope Benedict XVI, came to this conviction through personal experience.

In November 1996, attending a meeting in Rome dealing with care for the sick, he recounted a deeply personal experience. He spent his boyhood in a little town in Bavaria, in southern Germany. Everybody knew everybody else. Families were unusually close.

Among his relatives was a cousin who was the same age as young Joseph. This cousin had been born with Down syndrome, a disorder of the body’s chromosomes that frequently results in physical or mental complications, difficult to treat. Nothing removes the basic problem.

When young Ratzinger and his cousin both were 14, authorities arrived, seized the cousin, took him to places unknown, and he never was seen again. As might be imagined, the cousin ‘s parents were beside themselves, and the entire family was desperate with worry.

They feared the worst, because across Germany, again and again, government actions occurred to rid society of anyone who might be a “burden,” or who would never experience “quality of life” — burden and quality being determined by public officials.

It was all very scientific. The preferred way to end the lives of the unfortunate “unworthy” was to inject lethal poison into them, but poisons cost money. Leaders publicly debated. Would starvation be more economical?

Located in Bavaria was Dachau, one of the government’s most notorious death camps. The Ratzingers and their neighbors knew it was there. They knew that Dachau incarcerated priests, and Protestant clergy, who dared to speak against the powers that be, and they knew that thousands upon thousands of Jews were imprisoned at Dachau, the majority of whom had done nothing wrong but were ruthlessly and systematically tortured and slaughtered.

It was traumatic for adolescent Joseph. He never forgot the cruelty of what surrounded him. He also saw figures, beginning with his own bishop, Cardinal Michael von Faulhaber, the archbishop of Munich, risk their lives repeatedly by condemning outright the practices of the government in so many instances and in calling Catholics to live by, and to respect only, the Gospel of Jesus.

Then, there was Pope Pius XI, who led the Church from 1922 to 1939. Everyone knew about the pope’s disgust with these German policies, a disgust that neared fury. On Passion Sunday in 1937, the pope issued a letter to German Catholics condemning what was happening in their midst, and he sent the letter to the people under the most unusual circumstances.

Since the controlled German media would never publish, or even mention, the letter, Vatican figures literally smuggled it into Germany and carried it in the best tradition of the cloak and dagger to German priests, who were ordered to read the letter aloud to congregations on Passion Sunday, replacing their sermons.

An altar server in his little parish, Joseph Ratzinger watched this intrigue and understood how important the papal letter was.

Joseph Ratzinger saw humans make genuinely awful decisions. He saw his entire society make awful mistakes, and he decided that the Gospel of Christ, relentlessly and exactly put forward by the Church, is the only answer.

As time passed, young Ratzinger was drafted into the German army, deserted, was captured by the Americans, held as a prisoner of war and then went to the seminary.

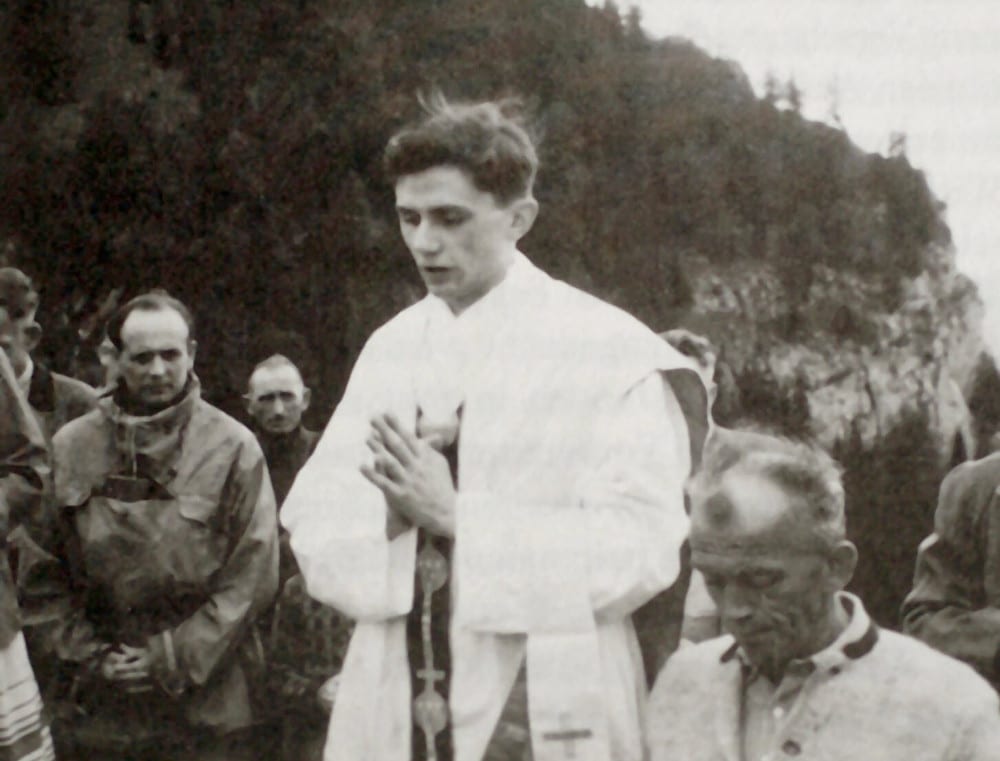

On June 29, 1951, he was ordained a priest by the legendary Cardinal von Faulhaber, and he began his priestly ministry in a country almost paralyzed by slavishly accepting the evil ideas of Adolf Hitler. Exceptionally bright, he studied theology at the graduate level, earned a doctorate and became a professor of theology.

Thus began a career that has been called one of the greatest contributions to theological reflection in a century.

In 1977, Pope St. Paul VI called him from his classroom to be archbishop of Munich, Germany’s most prestigious diocese. Within months, Paul VI named him a cardinal. After four years in Munich, Pope Paul appointed Ratzinger to head the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, as it then was called, the Vatican department charged with safeguarding the purity of the beliefs proposed by the Church.

Pope St. John Paul II kept Cardinal Ratzinger in this office throughout John Paul’s long reign. When St. John Paul II died in the spring of 2005, the world’s cardinals elected Cardinal Ratzinger as the new pontiff. He took the name of Benedict XVI, explaining that he revered St. Benedict, the 16th-century founder of the Benedictines, because St. Benedict so effectively placed Christ at the center of human life and at the center of his own life.

On Feb. 28, 2013, in a moment electric for the Church, Benedict XVI resigned. He lived in virtual seclusion until his death.

From the days of his being a professor, through his considerable involvement in the Second Vatican Council, to his service as Munich’s archbishop, in his time as head of the Doctrine of the Faith, and even as Pope, Joseph Ratzinger was a prolific author. Many of his writings are considered masterpieces of theological reflection.

As a bishop, and as pope, he made many decisions, affecting many people.

No one in similar circumstances would escape controversy or criticism. Recently, his actions, or alleged failures to act, while he was archbishop in Munich, regarding clergy sex abuse, have been questioned, at times harshly.

He forthrightly apologized for any misstep on his part, and he evidently learned that sexual abuse of youth has grave consequences. He learned this, as psychiatrists of his time finally learned it, as legislators learned it at last, as law enforcement learned it, as parents and teachers learned it, and as popular opinion learned it.

Learning was his life, as much as teaching. Learning is a necessity for any human, especially for the Christian. Learn the realities of life, but judge reality in the light of the Gospel.

He was a man of faith, who loved the Lord, but he was a human, nothing less, but nothing more. In a last testament, admitting his humanity, and the ideal that he found in Jesus, he asked forgiveness from anyone whom he may have hurt.

At his passing, the world might note from his frankness and contrition that all humans are limited, and that anyone may succumb to terrible things, as did those who took Ratzinger’s young cousin away long ago.

Humans also can be fearless, relentless, and a solution to evil, as were Pope Pius XI, Cardinal von Faulhaber, and so many of the innocents languishing at Dachau.

Pope Benedict XVI, Joseph Ratzinger, learned from experience that loving Christ, and following Christ, as presented by the Church, and nothing else, make life good and beautiful, always, invariably.

May he rest in peace. With him, pray, “Jesus, I love you.”

Msgr. Owen F. Campion is OSV’s chaplain.