Two substantial new historical studies of Pope Pius XII’s response to the Jewish Holocaust reach sharply opposed conclusions. Not surprisingly, it’s the negative criticism of Pius rather than the documented defense that’s getting attention, including puff-piece interviews by The New York Times and the Associated Press.

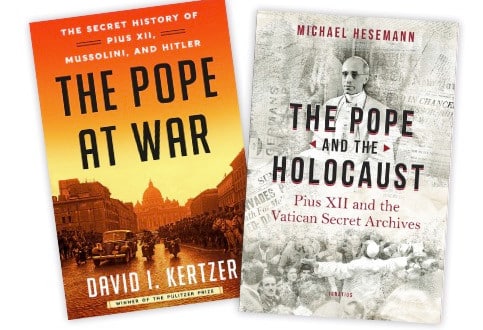

Brown University historian David Kertzer in “The Pope at War” (Random House, $37.50) maintains that concern for the Church in German-occupied territories led the pope to pursue what the AP calls “a paralyzingly cautious course” on Hitler. Kertzer’s negativity toward Pius won’t surprise readers of his Pulitzer Prize-winning 2014 volume “The Pope and Mussolini,” with its open dislike of Cardinal Pacelli, Pius XI’s secretary of state and successor.

Cautious the pope unquestionably was, but hardly inactive. German historian Michael Hesemann in “The Pope and the Holocaust” (Ignatius Press, $19.95) concludes that while Pius XII couldn’t have prevented the Holocaust, without his efforts the number of Jews killed would have been far higher — a judgment evidently shared by the many prominent Jewish individuals and groups heaping praise on him after the war.

Cautious the pope unquestionably was, but hardly inactive. German historian Michael Hesemann in “The Pope and the Holocaust” (Ignatius Press, $19.95) concludes that while Pius XII couldn’t have prevented the Holocaust, without his efforts the number of Jews killed would have been far higher — a judgment evidently shared by the many prominent Jewish individuals and groups heaping praise on him after the war.

That Pope Pius was too timid to take risks is belied by the fact that early in the war he served as a communication channel between German military officers plotting to overthrow Hitler and the British government. And the failure of the plot was in no way the pope’s fault. Hesemann tells this story in fascinating detail.

It’s true, of course, that except for a passage in his 1942 Christmas message (which in fact infuriated Hitler), Pius XII didn’t publicly protest Hitler’s murderous racial policies. There was, however, good reason for that.

In July 1942, with the deportation of Dutch Jews to Auschwitz underway, the Nazi chief in the Netherlands agreed to spare Jewish converts to Christianity if the Catholic bishops and leaders of the Reformed Church kept silent about a joint protest they’d sent him. The Reformed leaders agreed, but the archbishop of Utrecht, Netherlands, had the protest read at Masses throughout his diocese. Five days later, the Nazi boss ordered all Catholic Jews arrested and sent to Auschwitz. That included Carmelite Sister Teresa Benedicta of the Cross (Edith Stein), who was canonized in 1998.

Pius XII took the Dutch lesson to heart. More important than words — for which others would have suffered — he set Vatican diplomats to work protecting Jews all over Europe, in some cases securing visas for them to escape to safe countries, elsewhere winning postponement or cancellation of orders for their seizure and deportation. These efforts, too, are covered in detail by Hesemann.

Both historians focus on events in October 1943 when the German occupiers of Rome began rounding up local Jews for the same deadly purpose.

Kertzer makes much of the fact that the Vatican concentrated on securing the release of the Christian converts among the 1,259 seized in the first sweep. But why not? Those were the ones the Germans had expressed willingness to release. Meanwhile, at the pope’s order, Rome’s convents, religious houses and the Vatican itself, along with the papal residence at Castel Gandolfo, sheltered Jews by the hundreds. Hesemann puts the number saved this way at well over 6,000.

But still — why didn’t the pope speak out publicly against Hitler? Kertzer blames it on fear. Hesemann says Pius believed “that speaking is silver, but helping is gold — and that the highest axiom must always be to save human lives.” Six million Jews died in the Holocaust. Hesemann calculates that without Pius XII’s efforts, it would have more like 7 million.

Russell Shaw is a contributing editor for Our Sunday Visitor.