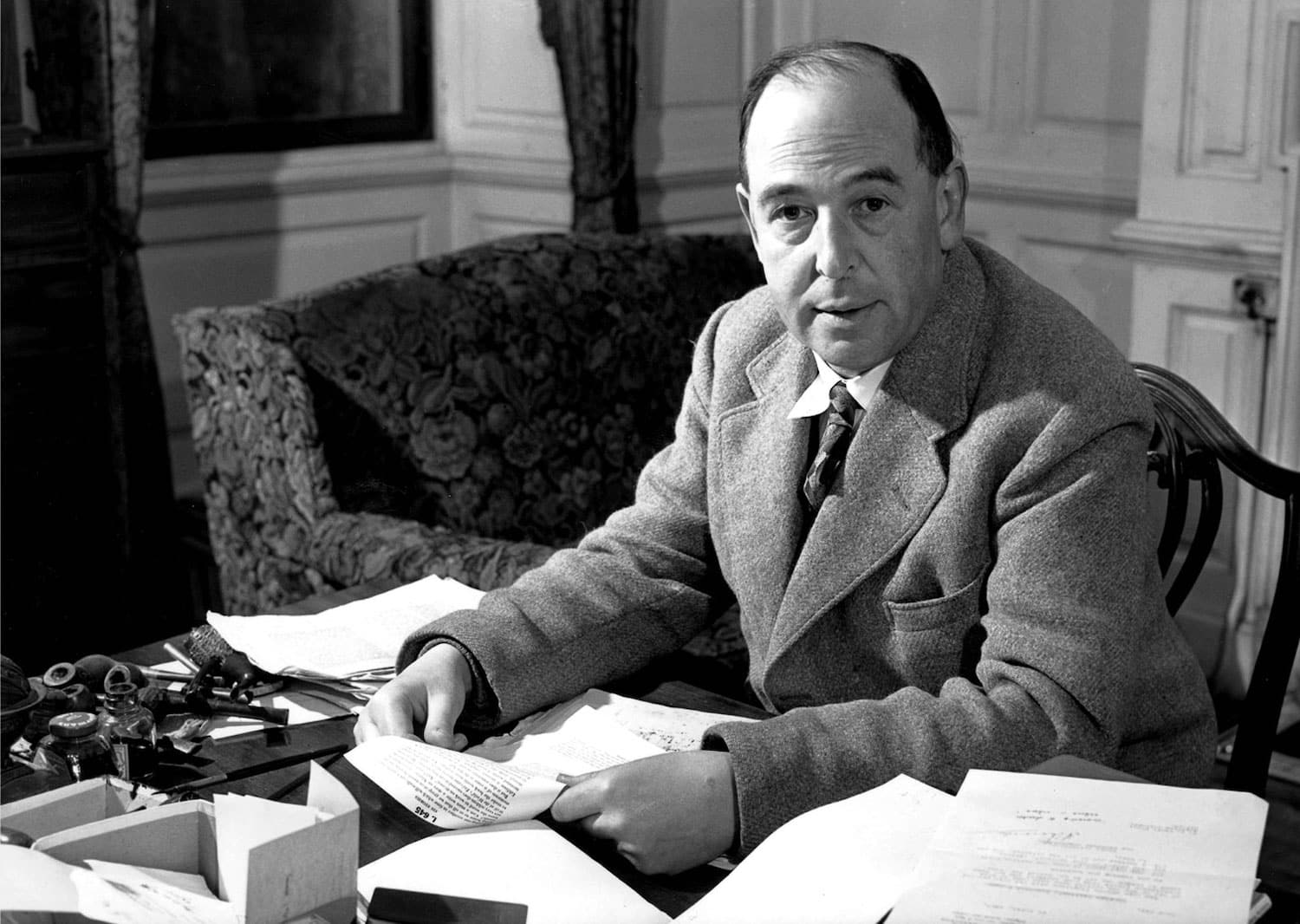

Recently I read, for the first time, C.S. Lewis’ spiritual autobiography “Surprised by Joy” (HarperOne, $16.99). Toward the end, as Lewis converts first to theism and finally to Christianity, Lewis makes mention of a “Great War” that he engaged in with Owen Barfield in those same years. That Great War with Barfield, often described as the “first and last Inkling,” having outlived the more famous members of that Christian literary group (Lewis, Charles Williams, and J.R.R. Tolkien) by decades, played a crucial role in breaking down the intellectual barriers that once prevented Lewis from acknowledging Christ as the Son of God. (Barfield wrote his own accounts of the Great War in several essays after Lewis’ death.)

Lewis and Barfield fought their Great War over the role that imagination plays in bringing us to a knowledge of higher things. Lewis eventually acknowledged that imagination could help man discover meaning, and this acknowledgment played no small role in his conversion; but to him, “meaning” was something different from “knowledge.” To oversimplify, “meaning” may be true or false, but “knowledge” is always true.

Barfield (again, to oversimplify) argued that the meaning we derive from poetic imagination can indeed lead to knowledge (and may even be synonymous with knowledge). At the heart of their disagreement (Barfield believed) lay the reality that Lewis largely accepted the epistemology — the theory of knowledge — most commonly associated with five hundred years of modern science, an epistemology I described in my last column as “what you see is what you get.”

While acknowledging the tremendous strides that modern science has made in advancing our knowledge of, and especially mastery over, the natural world, Barfield believed that the Cartesian distinction between subject and object on which modern science is based is outdated, and that man, rather than viewing the world as something entirely external to himself, participates in the reality of everything around us. In other words, we see the world from the inside out, and our imagination plays a vital role in our experience and knowledge of the world.

Classical and Christian understanding of teleology

My purpose in this column is not to refight the Great War (though a longtime reader of these columns might suspect, correctly, that I fall more on the side of Barfield than of Lewis and believe imagination to play a central role in how we come to understand the reality of the Incarnation and of the Eucharist), but to point to another effect, little remarked, that arises from the epistemology that Lewis by and large accepted — namely, the withering away of the classical and Christian understanding of teleology.

Teleology, put simply, posits that created things have an intrinsic purpose that is understood in terms of their end rather than in terms of an endless series of cause and effect. The classic example is the acorn, whose purpose is to grow into an oak. Modern science can explain how an acorn, under the right conditions, may become an oak, but it denies that the acorn can be explained in terms of its final existence as an oak. A boy becomes a man through a series of physiological processes, but from the progression of those processes, we cannot say that the purpose of a boy is to become a man (much less that the purpose of a man is to spend eternity in the presence of his Creator).

A teleological view of creation provides meaning that the modern scientific understanding of cause and effect does not. And it takes imagination to arrive at that meaning, to see the mighty oak in the humble acorn, to see the man in the boy, to see the saint in the man, to see the Son of God in Christ Jesus. Trapped in the determinism of the modern scientific worldview, even many of those who profess Christianity find it easier to see God as utterly transcendent, as a deistic clockmaker who set the chain of cause and effect going but then stepped back from the world, rather than as the Father who sent his only Son into the world to draw all mankind to himself through his Cross.

If we desire to bring the good news of Jesus Christ to all, we need a new teleology, a way to see all things once again through their final cause. And for that, we need a revitalized imagination, a new way of looking at the world, that imbues all creation with meaning. One might even call that new vision a Eucharistic worldview.