For many Catholics, this has been a difficult time. Many have not been able to receive the Eucharist for nearly two months. In parts of the country, this is now changing, and bishops are authorizing public Masses, with modifications to allow for proper social distancing. This is intended to avoid spreading the virus.

However, almost as soon as this was announced, it ignited a new front in the liturgical wars. Some bishops have restricted reception of holy Communion to solely in the hand and prohibited holy Communion on the tongue. Can they do this canonically?

Before I answer, let me say that many traditional Catholics have suffered greatly from some who flouted the law and their rights in the past. There has been a lack of charity and justice shown toward traditional Catholics. Those who often talked about being “inclusive” tend to exclude those who are more traditional. This has often created division by insisting on liturgical practices that often deviate from liturgical law. It has created a hypersensitivity among traditionally oriented Catholics. Therefore, they react quickly to defend what they see as their rights.

That said, the answer is yes, bishops can restrict the manner of reception of holy Communion temporarily in extraordinary circumstances. A pandemic certainly qualifies as an extraordinary circumstance. Many will point to Redemptionis Sacramentum, which says, “Although each of the faithful always has the right to receive holy Communion on the tongue, at his choice …” (No. 92). This looks pretty cut and dried that it’s up to the communicant, but it’s not quite that simple. The minister of holy Communion and the other faithful also have rights.

According to the Church’s law the rights of the faithful are not absolute. The Code of Canon law states in Canon 223 that “in exercising their rights, Christ’s faithful, both individually and in associations, must take account of the common good of the Church, as well as the rights of others and their own duties to others” and that “ecclesiastical authority is entitled to regulate, in view of the common good, the exercise of rights which are proper to Christ’s faithful.” In addition, the bishop is the moderator of the liturgy in the diocese (see Canon 835, which states that “the sanctifying office is exercised principally by bishops, who are the high priests, the principal dispensers of the mysteries of God and the moderators, promoters and guardians of the entire liturgical life in the Churches entrusted to their care”).

These canons tell us that for the common good and to protect the rights of others, the bishops can restrict rights in ways they would not in normal times. The common good is that the virus does not spread and others have the right to worship without being needlessly exposed to it. It is a matter of justice and charity to avoid the spread of a deadly illness. This is a duty that we have toward our neighbor. This restriction is a temporary measure to allow for Mass and the reception of holy Communion while avoiding the spread of illness. In canon law, according to the regulae iuris, if one can do the greater, one can do the lesser. If the bishops can restrict public Mass, which they can, they can restrict the manner of receiving holy Communion.

St. Thomas, in the Summa (First Part of the Second Part, Q. 96) states:

“Now it happens often that the observance of some point of law conduces to the common weal in the majority of instances, and yet, in some cases, is very hurtful. Since then the lawgiver cannot have in view every single case, he shapes the law according to what happens most frequently, by directing his attention to the common good. Wherefore if a case arises wherein the observance of that law would be hurtful to the general welfare, it should not be observed.

“For instance, suppose that in a besieged city it be an established law that the gates of the city are to be kept closed, this is good for public welfare as a general rule: but, it were to happen that the enemy are in pursuit of certain citizens, who are defenders of the city, it would be a great loss to the city, if the gates were not opened to them: and so in that case the gates ought to be opened, contrary to the letter of the law, in order to maintain the common weal, which the lawgiver had in view.

“Nevertheless, it must be noted, that if the observance of the law according to the letter does not involve any sudden risk needing instant remedy, it is not competent for everyone to expound what is useful and what is not useful to the state: those alone can do this who are in authority, and who, on account of such like cases, have the power to dispense from the laws. If, however, the peril be so sudden as not to allow of the delay involved by referring the matter to authority, the mere necessity brings with it a dispensation, since necessity knows no law.”

Therefore, the Angelic Doctor gives the rationale that for the common good, in extraordinary circumstances and in matters of urgency, rights can be regulated by those who have authority. The bishops are acting within Catholic tradition and canon law. When the necessity ends, so will the authority of these restrictions on the reception of holy Communion.

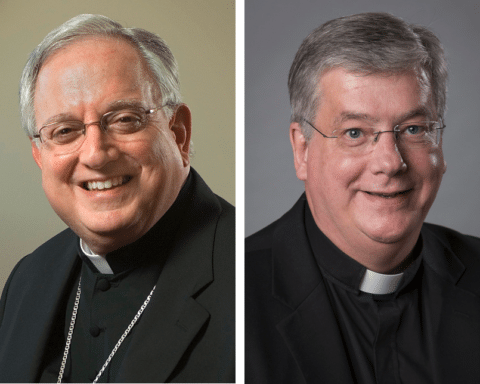

Bishop David D. Kagan of Bismarck, North Dakota, who is also a canonist, wrote: “The general principle of Church law, which includes liturgical law, is that Church law always admits exceptions unless the proper authority (pope or bishop) makes it explicit that there is no exception to it. Let us also keep in mind those who are now making an issue of a certain form and discipline have missed what is essential altogether. It is not our physical posture that determines our moral and spiritual worthiness to receive holy Communion, it is the state of our souls.” Canon 87 reflects this principle in giving the bishops the authority to dispense from universal and particular law, especially when there is imminent grave harm.

Now is not the time to fight unnecessary battles in the liturgical wars. We should rejoice at being able to assist at Mass again. If someone in conscience feels he cannot receive holy Communion in the hand, he can simply refrain from reception. We are not obliged to receive holy Communion every time we assist at Mass. Mass is more than the reception of holy Communion. Instead of fighting, to the detriment of our Christian witness, let us unite together in the supreme worship of the Triune God and especially pray for an end to this pandemic. Many are seeking God in this time of suffering, and we have an opportunity to introduce them to the Lord Jesus Christ, who conquered death and offers the hope of eternal life. Let’s focus on that mission and obey the supreme law of the Church, which is the salvation of souls.

Father James Goodwin writes from North Dakota.