“There is no affordable housing,” said Stephen Moses.

The 45-year-old explained that, despite having full-time employment, he was not saved from experiencing homelessness.

“Even if you’re working full-time, even if you have some savings for first and last month’s deposit, the rents are so insane that you just can’t afford them,” said Moses. “It’s so hard just to find a place and to be able to afford a place.”

Moses is a dual citizen of Canada and the United States. He was born in Toronto but grew up in South Florida. He returned to Canada as an adult and lived in Vancouver before moving to Halifax — where he now resides — on account of the lower cost of living.

That affordability has since ended.

“It’s gone up so much the last few years,” said Moses. “Now it’s just as expensive to live here as to live anywhere.”

When Moses relocated from Vancouver to Halifax, he found an ideal living situation where he paid much less rent than he did in British Columbia, but for a much better apartment.

“That was perfect,” he said. “I was living on high heaven here.”

That was until Moses was evicted from his apartment for smoking a cigarette on his balcony “after the building had gone non-smoking.” Moses became homeless.

“When I got evicted from there, I couldn’t find anywhere else that I could afford,” he said. “Even if you can afford $1,200 a month, you can’t find anything for that.”

Moses pointed out that this was the case even with having steady employment. “I’m a cashier at a major retailer,” he said. “I’ve been working continuously all through this.”

Moses’ circumstance is far from isolated. Hundreds of people within Halifax are unhoused. Their predicament is part of a growing crisis across both Canada and the United States where the rising cost of housing has, in part, contributed to the number of people experiencing homelessness.

The Church responds

The severity of the situation prompted the leader of the Archdiocese of Halifax-Yarmouth, Archbishop Brian Dunn, to name homelessness as one of four pastoral priorities within the archdiocese for 2021.

In expounding upon the priority of homelessness, the archdiocesan website quoted Jesus’ assertion that the poor would always be with us (cf. Mt 26:11). In light of that fact, it said, “as followers of Christ today we must always seek ways to help those in need.”

To that end, in a letter to the faithful dated Jan 28, 2021, Archbishop Dunn asked each parish to submit “an inventory of efforts that are being made to assist the needy and homeless.”

John Stevens, manager of pastoral life and new evangelization within the Archdiocese of Halifax-Yarmouth, noted that amongst the existing efforts was a parish that had one basic shelter on its property that housed someone in need.

“It went very well,” said Stevens. “They had a fellow in there. He stayed for the winter. He was able to then secure an apartment in the summer, and it was positive.”

The archdiocese investigated expanding the program which, Stevens said, involved the assistance of an engineering firm to design a shelter that was “a little bit more robust” than the initial one.

He recounted how, despite discussions with the city taking some time, he is sympathetic to the concerns and challenges involved in receiving municipal approval because “the building code is there to protect people.”

“There was a lot of negotiation,” said Stevens.

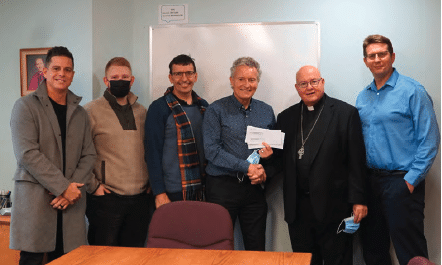

It was late November 2021 before all these variables were “figured out with the city and the engineering firm,” said Stevens. Then the fundraising began, with each shelter set to cost $11,500 CAD.

What happened next wasn’t anticipated.

“We raised enough for the shelters within a few weeks after that,” said Stevens. “In fact, more than enough that we were able to do some upgrades.”

“It happened very quickly,” he said.

Stevens recalled how some people would call up and say, “put us down for one.” He wasn’t sure if this meant one hundred dollars. They’d respond, “‘no, one shelter.'”

“A group of Christian churches got together and came to visit us with enough to purchase three or four shelters,” said Stevens. “They’d taken a collection amongst themselves.”

There was lots of amazing outpouring from the community, from other Christian churches, from people of the archdiocese, he said. “It really was amazing.”

The next step was also remarkable.

Twenty emergency shelters were erected and put on parish properties throughout the archdiocese to accommodate single occupants. This also happened in a matter of weeks.

“We got the first shelters up in December and got the last ones up in the first or second week of January,” said Stevens. “We’re talking maybe six, eight weeks at the most, where we were able to build these 20 things, put them in place and have people in them.”

“It was extraordinary in terms of engineering and project management,” he said.

The response was overwhelming and spoke to the need as well as to how the project resonated with people.

“Everyone just knew something had to be done,” said Stevens.

He recounted how the city was supportive and enabled what was necessary for the project.

“We were putting up shelters and getting permits for them the same day and moving someone in that evening,” said Stevens.

He witnessed a “confluence of the common good” to get the initiative off the ground with “the Catholic desire for charity” and the public’s awareness of “this issue of housing and affordability and homelessness.” Stevens said no one wanted to get in the way of doing something about the situation.

He also acknowledged how the prevalence of this issue can be a bit paralyzing because a person may wonder what they can do. “Thinking about it in the total scope, it gets a little overwhelming,” said Stevens.

“So, we just said, ‘well, here’s a specific project that doesn’t solve the problem. But it does keep 20 people warm this winter who are living in tents right now,'” he said. “We have property, and we have people, and we have desire.”

If everybody can help 20 people, then you can do something about a bigger problem, Stevens said.

Small, crisis shelters

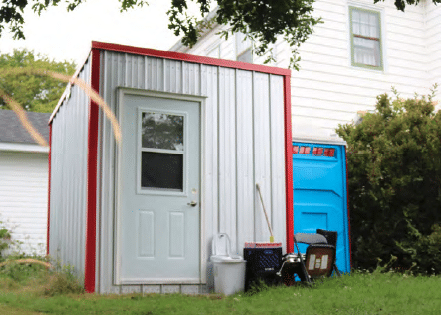

The emergency shelters are an 8’x8′ structure which look like a small shed.

“Eight by eight is a minimum size for a bedroom under the building code, like a little mini-bedroom,” said Stevens. “They have the bed built into the wall.”

The small structures include a heating unit, metal siding and a metal roof, as well as a distinctly colored edging around the exterior.

They look nice, said Stevens. “They’re not just plain plywood and Tyvek.”

Within the shelter there’s a USB charge port to plug in devices as well as the little USB-powered lamps which are provided. There’s also an overhead light, smoke and carbon monoxide detectors, a window and storm door.

“That’s it,” said Stevens.

Each parish that is a host site has between one and three of these emergency shelters on its property.

The location of the shelters at each of the participating parishes depended on a series of variables related to city requirements as well as practical considerations, including the ability to run an electrical line from an existing parish building.

Perhaps as significant in the shelters’ descriptions is what is not included. There is no indoor plumbing, cooking facilities or refrigeration. Instead, residents have access to a portable toilet.

This is telling as to what the shelters represent because they are, Stevens stressed, crisis shelters, not homes.

“If it was a tiny home then it would be permanent, someone could live there forever,” said Stevens. “But a tiny home also has other requirements like plumbing.”

That distinction is significant for the project, including in a formal sense.

Stevens explained that the building permit specifies that these are temporary shelters for crisis situations. “We’ve carved out a very narrow space for ourselves in the building code,” he said.

The archdiocesan employee also makes a connection with what Pope Francis said early in his pontificate, wherein the pontiff used the image of the Church as a field hospital.

Stevens likened this image to what is happening with the emergency shelters.

If you went into a disaster zone, you could pop up 20 of these shelters, and people could live in them, said Stevens. “That’s the mindset that we’re operating under here.”

“People in crisis — come stay with us,” he said. “We’re going to help you as best as we can with whatever we have to give.”

There is another variable that is implied in these very simple structures. Namely, that there are other basic needs that must be provided for via other avenues of support.

“The volunteers at the parish are quite extraordinary,” said Stevens. “Really, they’re the key to this whole thing.”

Stevens recounted how, initially, parishes were approached to get a “sense of who would want” a shelter and “who would be able to support it.”

“There needed to be the commitment on the ground for that care part of it as well,” he said. “Funding them and putting them up is actually the easy part.”

Stevens explained that parish volunteers do regular check-ins with shelter guests. In many instances they are “providing food or access to gift cards or access to the hall for showers or laundry.”

Some parishes have a food program, whether that is a daily lunch or people cooking regularly and dropping off meals.

If a hosting parish was unable to provide for these other needs, then its guest would be pointed in the direction of where these basics could be met.

The participating parishes also needed to make commitments to shoulder ongoing responsibility for the shelters such as the cost of the electricity which, up to this point, hasn’t been substantial, but is still a consideration.

Fitting a description

In a sense there is a certain profile of those for whom these emergency shelters are a good fit.

“We don’t have counselors, we don’t have 24/7 monitoring so certain levels of mental health or physical health needs, we just can’t support,” said Stevens.

For the agencies and groups who work with people suffering homelessness, the emergency shelters are one option for them to refer specific clients to. “We really depend on referrals, who have some basic survival skills,” said Stevens.

He explained that the shelters require a degree of independence with regards to acquiring food, showers and laundry. “Most of the folks know how to access those things anyway,” said Stevens. “In some ways they were already doing them because they’re coming from the street.”

Thus, the typical guest at one of the church shelters is somewhat experienced. Even so, they are still supported in knowing where to access different resources.

As an example, Stevens cited the role of public facilities. “At certain community centers, like pools and gyms that are owned by the city, you can get access to the showers there just by showing some ID,” he said.

Parish volunteers would assist guests in navigating these options.

The shelter guests, as well as their circumstances prior to moving in, are diverse. “It’s pretty varied,” said Stevens.

Some people had been staying in other basic shelters which were erected by a group of concerned citizens. A few came from the “hotel programs” wherein “during COVID, the province and city were funding temporary hotel stays for people who were living on the streets to get them out of the cold,” Stevens said.

However, a majority of the guests had been living in tents.

Stevens noted how significant it is, particularly for those coming from a tent, to have a place to store their belongings and a door that locks. “The stability that it offers is actually pretty important” and “can really improve the quality of life for a person,” he said.

Stevens outlined how, through having a fixed location, additional help is available to the guests, such as support workers knowing where to find them.

In a lot of cases the parishes have been able to arrange civic addresses for those shelters, said Stevens.

This is important because, if someone has a mailing address, they can receive income assistance. Thus, the shelters provide vital access to additional services and resources for their occupants.

Helping individuals

“It’s been a safe place for me to stay, which is the first time I can say that since I’ve been homeless, which has almost been a year now,” said Moses.

After he was evicted from his apartment, Moses said he stayed in a few shelters as well as a “tent city” erected within Halifax by fellow unhoused people. “The people of the church have showed so much support,” he said.

Though responses to the shelters have differed, Stevens said most guests are happy and grateful. Moses is one such person.

“I can’t even tell you how good the church has been to me with giving me gift cards and making sure I have showers every couple days, and laundry at least once a week, and they always make sure I have something to eat,” he said.

Moses referred to the former rectory on the church property. “That’s where we do our laundry and get our drinking water and everything,” he said of himself and his shelter neighbor.

|

— Stephen Moses |

“The church has been really good to me,” Moses continued. “They helped me store my stuff that couldn’t fit in my shelter.”

Moses voiced his appreciation for all these supports including having “clean clothes to wear to work.”

“I was just treated so well,” he said. “It’s been amazing.”

Temporary solution

At the outset the project was meant only to be for six months until May 31, 2022.

The initial scope was winter, said Stevens. “We wanted to just get people off the streets to survive the winter in a warm, dry, comfortable place.”

However, the housing situation in the city only worsened during that time, which meant the need for the shelters increased rather than decreased.

“We realized, ‘oh, wow, well, there’s just no place for them to go,'” said Stevens. “Even if they had money and they had jobs and everything was 100% hunky dory, finding an apartment right now in this province is very, very difficult, especially one that you could afford just making a regular wage.”

Accordingly, the archdiocese, in concert with the city, responded by extending the timeframe of the emergency shelters.

As well, to help facilitate summer housing, air conditioning units were installed in each emergency shelter. Stevens explained that this was a necessity because the tiny rooms were intended as winter accommodations.

The shelters were built to be warm on purpose, he said. “They’re very insulated and so if there was no air conditioner, I think they would just be unreasonably hot.”

The next step in the ongoing growth of the project was the archdiocese hiring a coordinator to help work with the guests in the shelters.

“She’s been able to meet with everyone — start to assess what their needs are,” said Stevens of the new coordinator. “Do they have a housing worker? If they don’t, can we connect them with them?”

Stevens said it’s important to “start to make a plan for each person.”

“We like to talk in terms of having every person have a trajectory,” said Stevens. “Because if they don’t, then these small shelters are going to wear thin over time for them and for their mental health.”

Stevens compared the situation in the city to a ladder that he said, admittedly, is missing many rungs. “So, if you’re on the street, these shelters are a step up,” he said. “They’re one rung on the ladder.”

Additionally, the archdiocese is discerning what more can be done long-term to fill in these gaps and missing rungs.

“They can stay as long as they need to, to take the next step,” said Stevens. “But we have to be working toward the next step.”

Even with the unique qualifications to stay in them, the emergency shelters are in high demand.

If someone goes, someone new is ready to come in almost immediately, said Stevens. “We’ve never had a vacancy.”

For those who have moved out of the emergency shelters, some have upgraded to a boarding house. Others have been on waiting lists for apartments and gotten in.

Stevens is confident that the project is making a difference.

He said there have also been those who “couldn’t live by the agreement and had to move on.” But Stevens believes a significant role was fulfilled regardless.

“They were safe for that time,” said Stevens. “They were cared for, for that time.”

For those who had to leave the shelters because it “didn’t work out,” Stevens said, “we try our best to send them out and find a support for them and make sure they don’t just fade away.”

Mental health

On a personal level, Stevens has learned much being involved with this program, including the troubling reality for those with mental health struggles.

Stevens observed that, whenever there was any sort of issue in the shelters, or it wasn’t working out with the guests, or they were unable to help someone, “the cause is often linked to mental health.”

“I’m actually shocked that in this country, you know, with our health care system, and everything that we have, that folks are walking around on the streets right now with no mental health care,” he said. “They can’t afford their medications that might actually help them. So, they might have enough one month, they might not have enough another month.”

As Stevens pondered these things, he noted that, as a society, we’ve “moved away from institutionalizing people.” Though he doesn’t necessarily disagree with that decision, a question remains. “But somehow, it’s better that they just kind of wander around on the street?,” he asked.

The “whole area of mental health and support and help” is concerning to Stevens. “It hit me very, very starkly,” he said. “It’s surprising and a little bit disturbing in your heart.”

Stephen Moses has witnessed something comparable.

“People end up homeless for all kinds of reasons,” he said. “But you know, what I found is, most of people . . . they do suffer from their mental health or addiction problems and that’s, I think, the big reason for homelessness.”

Christians’ core identity

Stevens believes initiatives such as the emergency shelters are central to Catholicism.

In discussing this, Stevens cited the example of Emperor Julian in Rome who said of the Christians, “‘see how they cared, even for our poor.'”

“I think it’s in the heart of the Gospel,” said Stevens. He referenced the Scripture, “where did we see you, Lord, in these people?” as well as Jesus’ response, “in the least of these you saw me” (cf. Mt 25:35-46).

“When you’re close to the poor,” said Stevens, “you can get close to Christ.”

The Archbishop of Halifax-Yarmouth expressed a similar sentiment in a letter about the emergency shelters project. “Corporal acts of mercy, including sheltering those who go without, are central to our Christian faith and teachings,” wrote Archbishop Dunn. “These are not optional projects — we are called to love ‘not in word or speech, but in truth and action’ (1 Jn 3:18).”

Stevens discussed this concept of “action.” He described how, when there’s a prevalent issue, people can sit around talking about how someone should do something about it.

| HOW TO DONATE |

|---|

|

For more information about the emergency shelters or to donate to the project, visit halifaxyarmouth.org/shelters. |

“You think that someone should be the government, or someone should be whomever,” said Stevens. “We just took the position that ‘oh, well, we’re someone and we have things.'”

He noted that one of the things the archdiocese had was the “success at this one parish” that initially had a shelter on its property. “So, if we bring what we have, whatever it is, however small — however stale our loaves are, or however stinky our fish are — the Lord can still bless it and multiply it.”

“That was just kind of our take on this — that we had to do something,” added Stevens.

This call to do good, to help others and be charitable is something Stevens believes Catholics “know in their core.” Thus, he strongly encouraged anyone who may be inspired to do something similar.

His suggestion, however, is to go in “with a willingness.”

There’s a will required for this, said Stevens. “Because when it gets difficult, you always have to get back to the original vision for ‘why are we doing this’ and that has to be kind of stuck in your heart.”

Nicole Snook writes from Canada.

“I can’t even tell you how good the church has been to me with giving me gift cards and making sure I have showers every couple days, and laundry at least once a week, and they always make sure I have something to eat.”

“I can’t even tell you how good the church has been to me with giving me gift cards and making sure I have showers every couple days, and laundry at least once a week, and they always make sure I have something to eat.”