— Paul VanHoudt, Erie, Colorado

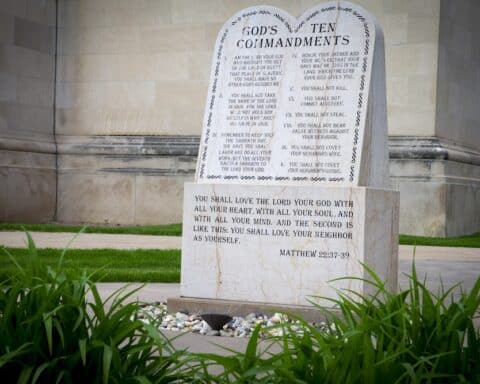

Answer: In general, laws can be distinguished from the punishments assigned to the violation of them. The moral law as revealed by God cannot change. But are the punishments incapable of change? This is less obvious. Punishments for the violation of any law, civil or moral, can vary based on contextual factors.

In the early days of ancient Israel, they were in a very vulnerable spot. Journeying in the desert, they were surrounded by hostile tribes and were days away from starvation. Everyone had to be at their post. If someone was goofing off, worshipping idols, disrespecting parents or lawful authority, or engaging is disruptive actives such as illicit sexual union, theft or drunkenness, they were a serious threat to the readiness and cohesiveness of the nation. Hence, the Law of Moses directed stiff penalties for even lesser sins: “If someone has a stubborn and rebellious son who will not listen to his father or mother … his father and mother shall take hold of him and bring him out to the elders at the gate of his home city, where they shall say to the elders of the city, ‘This son of ours is a stubborn and rebellious fellow who will not listen to us; he is a glutton and a drunkard.’ Then all his fellow citizens shall stone him to death. Thus shall you purge the evil from your midst, and all Israel will hear and be afraid” (Dt 21:18-21).

There was little time to engage in reparative or corrective measures. Note the reason: “Thus shall you purge the evil from your midst” (Dt 17:7). A nation in danger simply cannot survive in the face of foolish, sinful and disruptive behaviors; so the punishments are strong.

As Israel settled in the Promised Land, some of the punishments could be relented since the immediate threats were less. Punishments are often prudential matters and assess what is best of the individual and the community here. So, some of the “death by stoning punishments” began to recede.

When Jesus is questioned on the matter of the woman caught in adultery, he is clear with the woman that she should not commit this sin again, but as for stoning her, he resists the hypocrisy of the leaders before him. They have failed to produce the man involved (who should also be stoned, according to the ancient law), and they themselves do not impose every penalty prescribed by the ancient law.

In the end, we cannot simplistically reduce the prescripts of the ancient Law to man or God alone. The moral law is from God, but punishments, even if from God at the beginning, are not unchangeable and admit of prudential judgments.

One with the Father

Question: What does it mean when the same Jesus who said, “The Father and I are one” (Jn 10:30), also says, “The Father is greater than I” (Jn 14:28)?

— Eric Smithfield, Wagner, North Carolina

Answer: Theologically, we can distinguish two ways of understanding this text. Many theologians emphasize that Jesus is referring to his human nature when he says, “The Father is greater than I.” As God, he is equal to his Father, but as man, he is less than his Father. Other theologians remind us that, even in terms of his divinity, the Father has a certain greatness as the source in the Trinity. All the members of the Trinity are co-eternal, co-equal and equally divine, but the Father is the Principium Deitatis (the Principle of the Deity). The Father eternally begets the Son, the Son is eternally begotten, and the Holy Spirit proceeds from them both. Because Jesus proceeds from the Father from all eternity, he is in effect saying, “I delight that the Father is the principle of my being, even though I have no origin.”

Devotionally, Jesus is saying that he always does what pleases his Father. Jesus loves his Father. He’s crazy about him. He’s always talking about him and pointing to him. By calling the Father greater, he in effect says: “I look to my Father for everything. I do what I see him doing (cf. Jn 5:19) and what I know pleases him (cf. Jn 5:30). His will and mine are one. What I will do proceeds from him. I do what I know is in accordance with his will.”

Msgr. Charles Pope is the pastor of Holy Comforter-St. Cyprian in Washington, D.C., and writes for the Archdiocese of Washington, D.C. at blog.adw.org. Send questions to msgrpope@osv.com.