In Lent, we reflect on our taste for sin, which we need to do, but it’s such a massive and disturbing fact we can easily think too much about it or think about it in the wrong way.

“The devil loves to distract one from God’s love and mercy by worry about sin,” Caryll Houselander warned a friend. “The only cure for this worry is to concentrate, not on self-perfection, but on the love and tenderness of God.”

Her friend tended to exaggerate her failings “to be on the safe side.” Houselander thought she’d missed the point.

God, she wrote, does not want to “trip us up … rubbing His hands and saying, ‘Ha ha she forgot something! I’ll jump on her for that.'” The attempt to cover everything perfectly “would blind you to God’s loving desire to forgive you and take you close to His heart. Only one thing makes you safe, putting your trust in God.”

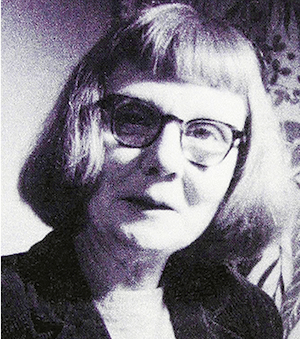

Reportedly the most popular Catholic writer in England after World War II, Caryll Houselander wrote several books, including an autobiography called “A Rocking Horse Catholic;” a Marian classic, “The Reed of God” and a close study of guilt called “Guilt.”

She kept up an extraordinarily sacrificial life, slept and ate little, and died of cancer in 1954, at the age of 53.

One Lenten resolution

Houselander wrote almost nothing about Lent, though she took it seriously.

She’d been sent to a convent school at 10. “In that convent there were really fasts, and feasts were really feasts,” she wrote in “A Rocking Horse Catholic.” “Lent was a serious business; we were taught to make countless little sacrifices, but taught too that to suffer with or for Christ was a supreme privilege. (If only every child learnt that early, how few people would carry psychological scars with them through life!)”

She wrote in “Guilt” that in Lent, “The time of austerity and fasting has come, the time for the lover to turn his face steadfastly towards Jerusalem, to know love … as the strength of the rock below the grass and the silence in the tomb hewn out of the rock.”

A friend new to the Faith had asked her advice for observing Lent. She would only share her own experience. “A mass of good resolutions, I think, are apt to end up in disappointment and to make one depressed.” The letter can be found in “The Letters of Caryll Houselander.”

She’d found only one resolution that worked for her: “Whenever I want to think of myself, I will think of God.” She didn’t mean long meditations, but “some short sharp answer” that would reorient her attention from herself to God. If she felt lonely and misunderstood, for example, she would answer herself with “The loneliness of Christ at His trial; the misunderstanding even of His closest friends.”

‘The sacrament of joy’

I think of Lent as a kind of weeks-long confession, with a continual examination of conscience, contrition and penance, all oriented to Easter’s great declaration of forgiveness. Seen that way, almost everything Houselander wrote about confession (much more than I can quote here) applies to Lent.

“Accept the feeling of guilt as just and offer it in reparation for all sin,” she advised another friend in a letter. And remember that confession “is first of all a contact, a loving embrace with Our Lord. All He asks is that you should want to be sorry, because you want to come back closer than ever to Him. … All the essential is done by God, on His side.”

She called penance “the sacrament of joy,” and not just for us but for the Father. “He rejoices as the father of the Prodigal Son rejoiced. He sees in the Christ-redeemed sinner, risen from the death of sin and living again with Christ’s life, his only beloved Son coming back to him, clothed in the red robes of his Passion.”

In “The Way of the Cross,” Houselander described beautifully what God creates in us through Lent and confession: “No matter how battered and bruised they had been by sin, the innocence of Christ was restored to them, they were restored to His beauty; no matter how darkened their minds and hearts had been by evil and by the oppressive sadness that follows upon evil, they shone now with the purity, the glory, of Christ of Tabor, clothed in His loveliness that burns with the splendour of a fire of snow. No matter how cynical and faded and old their sins had made them, they were restored to their childhood now, to Christ’s childhood. Now they could possess the kingdom of heaven in a wild flower, a stream of water or a star.”