This article first appeared in Our Sunday Visitor magazine. Subscribe to receive the monthly magazine here.

When I imagine the setting of Flannery O’Connor’s unfinished novel “Why Do the Heathen Rage?” I see Andalusia. I see O’Connor’s home, her front porch, her large trees, the fieldhand’s cottage in the back and her mother, Regina, pulling up weeds from Mrs. Tilman’s garden. Perhaps everyone who visits Andalusia sets O’Connor’s characters within the parameters of that small estate and its unexplainable appeal. “The Displaced Person,” “Good Country People” — few of her stories occur outside of white Southern farms run by strong mothers.

My family roots are only miles away from the nearby town of Milledgeville, Georgia. I grew up hearing O’Connor’s accent in the mouths of my kin. The first time I read O’Connor’s story “A Good Man is Hard to Find,” I pictured my grandmother hiding Pitty Sing in the car. We were a little less middle class: Instead of gloves, my grandma warned me not to have holes in my knickers so that, if I got into a car accident, folks would know I was a lady. The General wheeled around at his daughter’s graduation in “A Late Encounter with the Enemy” resembles my grandfather, proud of his Civil War ancestors and disappointed in me for not joining Daughters of the American Revolution. O’Connor’s cosmos is not foreign or freakish to me, though, like Dante’s allegory, her characters are turned inside out, with souls revealed through their bodies.

If you have not been to Andalusia before, the home has changed since Flannery died in 1964. Her mother kept it for a long time after her daughter’s death, and the estate remained in the family until 2003. Only recently was it donated to Georgia College & State University.

Once upon a time, you would drive up the red-dirt entry to the farm and visit the house and walk the pond without anyone’s permission. They used to sell vials of the pond water in a store set up in O’Connor’s entryway, like holy water of a sort to remember one’s pilgrimage to the uncanonized literary saint’s former dwelling.

These days all the merch is down the driveway in a building called the “Andalusia Interpretive Center.” O’Connor would have mocked the “innerleckchuls” for a name like that. The center has an enlightening showroom of O’Connor artifacts: her dresses, paintings, miniatures and so on. But now the drive has been chained off and the trees cut away from the entrance when you turn off U.S. Route 441. It feels less like venturing back in time and more like you’re a groupie stalking your favorite band. You have to work to fancy away the interference.

The outside porch is screened in, a segue between air-conditioned paradise and the infernal heat of the farm. It’s where O’Connor often met her guests and invited them to sit in the rocking chairs and drink a Coca-Cola. (Flannery appreciated hers mixed with black coffee.) As she told Harvey Breit on national television in 1955: “I’m a writer, and I farm from the rocking chair.”

Rather than the colonnades that adorn some 19th-century Southern plantation houses, this farmhouse greets visitors with white banisters lining the porch. The house is topped with a red tin roof and red brick steps and red brick chimneys. For O’Connor, color mattered. In her stories, red is often associated with violence, blood or sin. But as in Dante’s “Purgatory,” where the red step symbolizes Christ’s love for the sinner, so too might this ascending threshold have more in common with grace than gore.

From suffering to revelation

Her room is meant to be as she left it. If you enter through the front door, it’s the first bedroom on the left, so that she could access it without too many stairs. There’s a fireplace still lined with knickknacks and photos of her family. The clock hasn’t been altered, stopping at 4:13 years ago.

O’Connor slept in a flat twin bed like a monk might use. A crucifix hangs to the left of the bed. More than a symbol of death, which O’Connor called “brother to (her) imagination,” the crucifix, for O’Connor, was Christus Victor. For a woman on aluminum crutches in the last decade of her life, the emblem was a wanted reminder. Now those crutches lean unneeded against the wardrobe.

Outside, two peacocks cry out for attention as though on cue for show, but the impromptu cries and conversation of the hundreds of fowl that O’Connor kept on the farm have died away with their mistress. On her desk, the Royal typewriter sitting amid an array of papers makes no more sounds. One has to remember the sound of O’Connor’s voice and rehearse lines from her letters to break the silence unfitting in the unoccupied home.

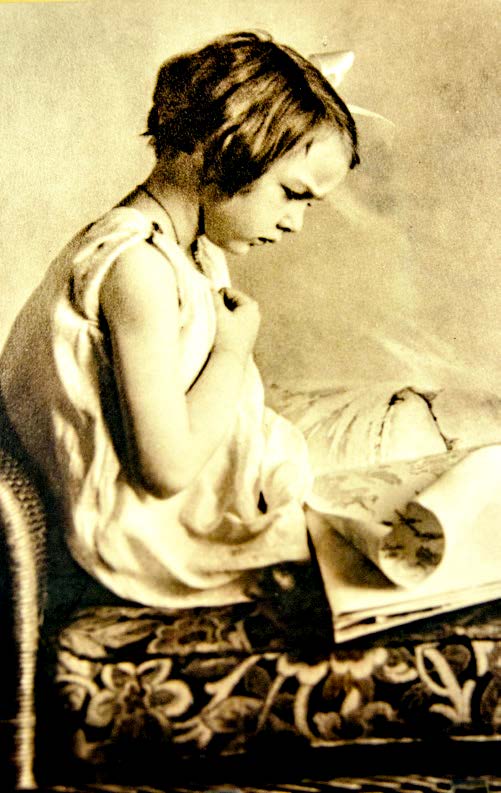

In the biopic “Wildcat” by Ethan and Maya Hawke, when the character of Flannery O’Connor sets herself to write despite her new diagnosis of lupus, she turns her back purposefully from the window and places a wardrobe behind her typewriter so that she sees nothing of interest when she works. At this moment of feng shui, peacock feathers are envisioned behind the excitedly typing O’Connor. The feathers, in the film, recall the “transfiguration,” which is how Father Flynn describes the displayed bird in “The Displaced Person.” Visiting this room reminds me of the absence of the woman herself but also helps me recall, with gratitude, the way she was transfigured from suffering to revelation.

The dining room once displayed her self-portrait, that imitation of a Pantocrator icon in which O’Connor dons a large straw hat like a halo and holds a pheasant cock. In a letter, O’Connor describes her image as “moon-face(d)” because of the lupus and the bird with “horns and face like the devil.” Earlier in her correspondence, she calls the pheasant her muse. In other words, O’Connor is giving the devil his due. Can you imagine eating oatmeal across from that image? But the portrait has been temporarily moved to join O’Connor’s other paintings. She often painted to practice seeing in new ways, art being a buoy to her writing.

O’Connor claimed to know nothing about the land except that it was under her. Regina (and, yes, O’Connor called her mother by her first name) did the farming. Over 500 acres originally. Once called “Grey Quail Farm,” the property was renamed “Sorrel Farm” when O’Connor’s uncle Dr. Bernard Cline purchased it in 1931. Bernard asked Regina to handle the bookkeeping; then, following his death in 1947, he bequeathed it to Regina and their brother Louis, who co-managed the farm and lived with his sister and niece. Once when Flannery was traveling by bus from Atlanta to Milledgeville, she met a descendant of the original owners and learned the first name of the farm was “Andalusia.” O’Connor convinced everyone to reinstate this enchanted moniker.

A separate history

What remains unseen from O’Connor’s room is the second home at the back of the property, that of the African American couple Jack and Louise Hill and their boarder, Willie “Shot” Mason, who worked for the O’Connor family. O’Connor’s world from 1925 to 1964 was segregated, so only now, decades later, are accounts of Black influence arising. Like the story of Emma Jackson, the domestic worker who cared for O’Connor when she was a child and resided in Savannah. Or the fact that the family of novelist Alice Walker lived minutes away on the same road as O’Connor.

Walker visited Andalusia after O’Connor’s death but before the home was curated into a museum. For Walker, the preserved home of O’Connor was a reminder of an undue separatism between white and Black writers in the South. I remember reading and loving Zora Neale Hurston’s novels in college, but how my stomach dropped when I heard she died in poverty, buried without a marker over her grave — whereas William Faulkner’s home, Rowan Oak, was memorialized and restored after his death.

O’Connor’s home has long been open to visitors, but the Hills’ home in the back was only restored in 2010. Only the greatness of O’Connor’s writing dissipated Walker’s rage at the injustice: “(O’Connor) destroyed the last vestiges of sentimentality in white Southern writing; she caused white women to look ridiculous on pedestals, and she approached her black characters — as a mature artist — with unusual humility and restraint.” When Walker tried to drive away from Andalusia, she wrote, a peacock blocked her path, proudly displaying its tail before her. Yes, please, transfiguration.